“When are you going to get a real job?” It’s a question that has followed me for my entire adult life. I mostly got it from my family, but the question was often heard from well-meaning friends who were sure that I was wasting my life by not pursuing a “career.”

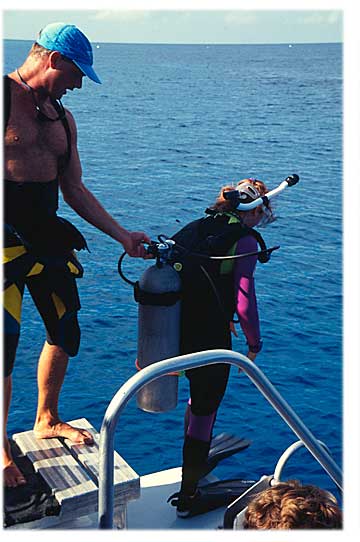

Of course, the concern came from the fact that, unlike anyone else my family and friends knew, I was a scuba instructor. And the term “real job” was just a polite way of asking why I wanted to be a beach bum.

I suppose that I understood the incredulous attitude, particularly from my family. I was, after all, the very first person in my extended family to graduate from college, and there were lots of hopes and dreams at stake. I had actually been trained to be a teacher, so to me, being a scuba instructor, while not what I or anyone I knew expected, was at least in the field of education. But try as I might to justify my decision in the eyes of those who cared about me, it couldn’t hide the real reason that I’d chosen such an unusual profession. I simply loved it. Of course, it didn’t hurt that a career in diving also allowed me to escape the brutal and depressing northern winters.

Another rationale that I dared not articulate to my family, and many of my friends, is that much of my life experience pushed me into doing something that most found, to put it politely, “nontraditional.” Most of the adults I’d known in my life worked at jobs that they hated. Fulfillment, if ever considered at all, wasn’t something the folks I grew up with got from an employer. They were satisfied with a paycheck; the thought that one should actually enjoy what they did for a living never occurred to them. I, on the other hand, came under the influence of a teacher, who later became a good friend. American education, he thought, was organized backward. He felt the idea of preparing someone for a vocation, and then only after they finish training hope that they liked doing what they’ve been trained to do was a tragically dumb idea. He insisted that the secret to a happy life was to first find the thing you love, and then figure out a way to get paid for it.

But don’t get me wrong; I didn’t consciously set out at the age of 19 when I became an instructor to enter the diving industry. Teaching scuba was, initially, merely a way to make some money doing something that I enjoyed. Surely, I thought, I’d eventually give it up. Well, it’s now 33 years later and in the minds of many, I still haven’t gotten that “real job.” Over the years my tax returns have classified my occupation as a consultant, technical writer, even a college professor, but to me, I’ve always considered myself just a well-educated scuba instructor. What’s interesting to me today is that many of those same folks who cautioned me against the mistake of letting my love dictate my career are retiring themselves. And more than one has admitted that, if they had to do it all over again, they’d have listened to their hearts rather than their heads, and made some very different choices.

I’m not recounting this story because it’s unique, or because I have some special insight into life. I make the point because, for the past three-plus decades, it’s one of the most consistent themes I’ve heard among dive professionals. Over the years I’ve spoken to countless men and women who, except for the details, have amazingly similar stories. I’ve found that it’s quite common for people to, like me, step into a scuba course merely to have fun, and one day find themselves earning their living by teaching diving to others.

The other interesting part of being a scuba instructor is that it doesn’t necessarily require a full-time commitment. I probably know as many, if not more, people who have enjoyed a long and successful part-time career as I do those who’ve invested their lives. There are also many jobs in the diving industry that don’t involve teaching. Career options in recreational diving run the gamut, from retailing to manufacturing to resort operations. But the entry ticket for almost any job in diving is an instructor certification. The rating is more than just a qualification; it’s the security code that gets you in the front gate of a career that others only dream of.

Whatever Floats Your Boat

Over the years, I’ve had the pleasure of training more than 1,500 scuba instructors. So I can tell you with full authority that being a scuba instructor can be one of those jobs you enjoy doing each and every day of your life. But believe it or not, fun just isn’t enough, because after awhile, even having fun can get old. (Trust me, it’s true.) What has continued to motivate me over the years more than even the fun, is the challenge. What other activity allows a teacher to deal in subjects as diverse as physics, physiology, marine science, mechanics, physical education, psychology and even public relations? You also have to have some pretty good counseling skills. Scuba instructors bring a whole new meaning to the term “jack-of-all-trades.” Our job believe it or not is at times tough, demanding and often unappreciated, but it’s never boring.

Still another reason that I was drawn to the profession is the opportunity for travel. I was reminded of this recently when I received the third renewal of my passport. Leafing through my old passports, I noticed stamps and visas from dozens of countries in the Caribbean, Middle East, Asia, and Pacific. I did more than 90 percent of those trips because of my career, and I paid for very few of them personally. Not a bad feat for someone who, as a kid, didn’t even know anyone who had a passport. My experience is anything but unusual. I’ve known colleagues who make my travel exploits look like I never left home. These are folks who’ve spent their entire lives as “travelers,” stopping to work only when the funds got low. And with a scuba instructor’s qualification, they never had a problem getting a job.

Of course, there are two sides to every story, so what’s the reality of becoming a scuba instructor? Any seasoned dive professional who has been in a management role can tell you that the diving industry is really no different from any other business. No doubt, there are lots of people out there who hold instructor ratings and would love to work in a resort. Still, demand typically exceeds supply. Why this is so is the first sobering reality of life in the dive business. Unfortunately, for many who have the dream, their perception is nowhere close to reality. Often, their idea of working in a resort means little more than getting a paycheck for being on vacation, and that’s no more the case in diving than it is in any job. As a result, while there are hordes of folks looking to “work in paradise,” when the rubber meets the road, there are never enough people with the right attitude and qualifications to meet the employment demand.

Assuming you’re still interested and you think you have what it takes, what’s the employment potential? Industry estimates are that there are about 2,000-2,500 dive stores in North America and about 600-700 dive resorts in the Caribbean basin. The Pacific and Southeast Asia are growing by leaps and bounds, but to what degree is really difficult to quantify. Certainly, given the immense area, there are far more opportunities in the Pacific than in the Caribbean. Dive stores, on average, employ 2.5 people full time and about four part-timers. Resorts often employ twice that number in their dive operations. In terms of the potential pool of employees, each year the various diver training organizations certify in the neighborhood of 8,000 instructors. Of that number, probably 2,000 or less seek full-time positions. So what about the other 6,000 or so?

As mentioned, one of the most appealing and unique aspects of the scuba industry is that it provides outstanding part-time employment opportunities. Over the years I’ve met scores of folks who essentially paid for the hobby both equipment and travel by teaching diving. In many cases, when they had opportunities for early retirement, diving actually became a second career. In fact, if you scratch the surface of a lot of middle-aged scuba instructors you’re likely to find a retired teacher, law enforcement officer or someone formerly in the military. The security of a pension, and a scuba instructor rating, has made for hundreds of fulfilling second lives, let alone careers. Many dream of this, but few actually make the dream a reality, and a large number of the successful few have done so with scuba instructor credentials.

On the other end of the continuum are youngsters who often have no desire to go to college. I’ve trained several kids right out of high school who have gone on to have highly successful careers in diving. Some are now working for training organizations, while others are still in the resort industry. A few now own their own businesses. I’ll never forget one kid who, only two years out of high school, wrote me this thank-you note. “I just wanted you to know what a ‘right’ decision it was to become an instructor. I knew I wasn’t going to make lots of money, but neither are most of the other people I graduated from high school with. The difference is that I wake up every morning to palm trees, put on a bathing suit and work with people who admire and respect me. I don’t know anyone else my age who can say that. To this day, I’ve never found another profession that can provide this kind of experience to those who are so young.”

Scuba Instructor: Not a Job for Everyone

Before you quit your job, sell your house and run off to the islands or open a dive store, you should know that a diving career isn’t all fun and excitement. In fact, you may not be cut out for it at all. A scuba instructor, first and foremost, has to enjoy and be capable of working with a wide range of personalities and circumstances. If your only motivation to become a diving educator is that you love diving, then take my most heartfelt advice and forget about it. People skills are just as important and often more so than diving skills. Patience is perhaps the most important requisite; and a close second is flexibility coupled with the willingness to work long and highly irregular hours. Get used to working weekends and holidays, too. You’re at your busiest when most others are enjoying themselves.

Before you quit your job, sell your house and run off to the islands or open a dive store, you should know that a diving career isn’t all fun and excitement. In fact, you may not be cut out for it at all. A scuba instructor, first and foremost, has to enjoy and be capable of working with a wide range of personalities and circumstances. If your only motivation to become a diving educator is that you love diving, then take my most heartfelt advice and forget about it. People skills are just as important and often more so than diving skills. Patience is perhaps the most important requisite; and a close second is flexibility coupled with the willingness to work long and highly irregular hours. Get used to working weekends and holidays, too. You’re at your busiest when most others are enjoying themselves.

The job duties of a scuba instructor aren’t what most newcomers expect, either. And to many it comes as a sad surprise. The reality of being an instructor at least full-time is that teaching is only a small portion of what you’ll do. Mainland-based instructors often work 40 hours a week at a dive store counseling customers or repairing equipment, then teach one or two classes a week on top of that. That means 60-hour weeks are commonplace. Think it’s easier at a resort? The norm for resort-based instructors is six days a week, and during busy periods seven days isn’t uncommon. Here, too, teaching is only a minor part of the job, but an instructor ticket is essential, if for no other reason than to get a permit to work in a foreign country. Many have left the industry disappointed that their dream of spending their days primarily as teachers never materialized.

As mentioned, effective communication and human relations skills are as essential as diving skills. What’s equally important is a professional appearance and demeanor. Those who don’t convey the image that guests or customers expect, or can’t communicate in a professional way, need not apply. Divers are sophisticated travelers, with household incomes typically in excess of $100,000 per year. The last thing they want to see after spending thousands of dollars to visit a dive destination is some beach bum in a dirty T-shirt emblazoned with some offensive slogan. Clients don’t mind your wearing a bathing suit, but they put their lives in our hands, so they expect someone who can instill professionalism and confidence.

The issue of responsibility is important to both understand and accept. In fact, my own family and friends began to take a very different view of my profession once they understood to what degree people trusted their well-being to me. Regardless of how much fun it may be, you can never take the responsibility lightly. If you do, people can die; it’s that simple. This can be a daunting realization, and anyone who lacks the commitment or maturity to shoulder such duties shouldn’t even consider the instructor route. Plus, above and beyond the moral issues, there are the legal implications. In the eyes of the law, scuba instructors are viewed as any other professional. This means they are held to a much higher standard of care than the average person when dealing with students, or when they’re acting in any capacity where they are receiving compensation. This is why a thorough orientation to the legal aspects of instruction as well as a requirement to maintain at least $1 million in professional liability insurance is required of all instructors in active teaching status.

Doing the Deed

Obviously, the first step in becoming a scuba instructor is becoming a certified diver, and if you’re reading this you probably have taken care of that or you are in the process of doing so. But that’s like saying that the first step to becoming a doctor is learning first aid; it’s only the beginning of a long process of training and gaining the requisite experience. Although the requirements for an instructor rating vary among the certifying organizations, on average expect to complete about 200 hours of training in prerequisite courses. That includes not only your entry-level course, but advanced, rescue and some form of supervisory qualification such as a divemaster or dive control specialist. Along the way you must also amass, at the minimum, 50-100 dives in a wide range of environments. And that’s what you need just to qualify for an instructor training course.

Preparation to become a scuba instructor requires mastery of diving theory, which includes a thorough grounding in diving physics, physiology, equipment mechanics and even a little marine science and oceanography. You’ll also need near-perfect diving skills, and an ability to deal calmly with stressful and unexpected situations like entanglements or out-of-air emergencies. In terms of physical prowess, a good measure of your preparedness is whether you can swim at least 800 meters (2,640 feet) using mask, fins and snorkel in less than 20 minutes. If you can’t, then it’s time to get out the ol’ exercise bike or buy some new jogging shoes.

During scuba instructor training, expect to learn a great deal about teaching, both theoretical and practical. You’ll master the art of planning and conducting classroom, pool and open-water lessons. You’ll learn how to organize training activities to maximize safety and efficiency. And, you’ll learn the requirements (termed “standards”) and nuances of conducting the various programs you’ll be sanctioned to teach. In all, expect about 60-80 hours of training above and beyond your prerequisite courses and perhaps a $1,400 to $2,000 investment for tuition, books and other fees. (This does not include your personal diving equipment or travel and living expenses while you are training.)

Once you’re qualified, the training process still doesn’t end. Most training organizations require, or recommend highly, that their instructors continue their education through more advanced courses, seminars or other in-service learning experiences. And just like the continuing education courses available to divers, instructors, too, have a full array of qualifications for advancement. Not only are good divers always training, so are good instructors.

I’ve never once regretted my decision to become a scuba instructor. It has taken me places that I never imagined I’d see, and provided me with experiences that few others can even dream of. Granted, it hasn’t all been a bed of roses. For me, six-day weeks have never been a norm, and the challenges of dealing with overly demanding clients and problem students have, at times, driven me straight up a wall. And I’ve never had any form of employer-supported pension or retirement plan. So it’s definitely not a job for everyone. But on balance, my career has confirmed my teacher friend’s premise: The secret to life is, indeed, finding out what it is that you love then figuring out a way to get paid for doing it.

Help Wanted

Being a scuba instructor is a fantastic part-time career, but many want to make it a full-time gig. As in any industry, diving has its own nuances when it comes to the all-important job hunt. But the ultimate goal in finding a job is the same as in any field — reaching out to potential employers and proving to them that you are the most qualified applicant.

As always, the first step is finding job vacancies, but this is simpler than you might imagine. Most training organizations provide free employment listings for their instructors. Also, many instructor training schools offer job placement to their graduates as a part of their services. Many will even help you in preparing a resume, and even teach you how to interview for the job you want. Another way of getting employment contacts is to attend local dive shows and seminars where you can network with potential employers. Many have headed off to such events with a briefcase full of resumes and returned home with a job offer.

Realistically, however, don’t expect employers to knock down your door. Remember that finding work is work in itself. In the most desirable locations, like the Caribbean, Florida or Hawaii, having an instructor certification is just the beginning. Think of it as a union card. It tells the employer that you’re generally qualified, but that’s about it. Those looking to make diving a career can never halt their education with just the standard instructor rating. Typically a scuba instructor entering today’s workforce is qualified to teach specialty courses like underwater photography, wreck diving, nitrox or oxygen administration. Many even pursue training in retail sales or resort operations. In the diving job market, this additional course work is like having a master’s instead of a bachelor’s degree.

While good training is important, it’s still no substitute for experience. So, when planning your job search, think about what you have done in the past that may be valuable to an employer. Skills that are in highest demand with dive stores are, not surprisingly, those in administrative, management or accounting. Still, the hottest skill is, and will probably always be, the ability to sell. After all, that’s the business dive stores are in. Anyone with a successful background selling anything is likely to place very high on an employer’s list of potential employees.

In the resort industry, things are a little different. While everything mentioned is desirable, resorts are usually in remote locations. That means when things break, as they inevitably will, someone has to fix them. So, a good diesel mechanic or compressor technician can work virtually anywhere he wishes. Those with other building trade skills will be high on a resort-based employer’s list, as well. Finally, as boats are a big part of the resort diving environment, a Coast Guard captain’s license is a hot commodity. But a captain’s ticket isn’t always necessary, and part of your job could be running a dive boat. Most dive resorts are outside the United States, and U.S. jurisdiction, so you could be captaining a dive boat sooner than you think. As a result, some solid boating experience will also go a long way in increasing your employability.