This is an interesting article that asked the question, are dive tables really used, are they relevant, and when will they be replaced by technology? It was becoming more apparent that after people were certified they weren’t using (or didn’t remember how to use) the dive tables as they were taught. Had the tables become irrelevant and should more training time be devoted to Computers and other products like the Recreational Dive Planner, which were taking over the planning and monitoring functions of the dive. The article laid out the case. It took longer than Alex projected, but the dive tables are rarely taught today.

— Mark Young, Publisher

Content below originally published in Dive Training, February 1999.

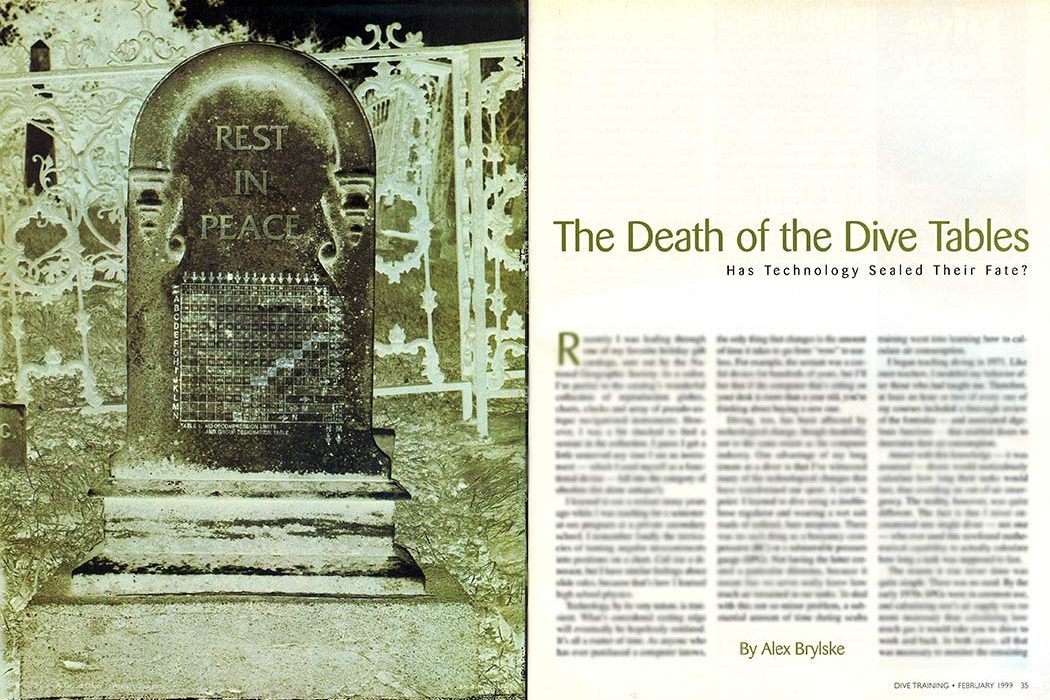

The Death of the Dive Tables: Has Technology Sealed Their Fate?

By Alex Brylske

Recently I was leafing through one of my favorite holiday gift catalogs, sent out by the National Geographic Society. As a sailor, I’m partial to the catalog’s wonderful collection of reproduction globes, charts, clocks and array of pseudo-antique navigational instruments. However, I was a bit shocked to find a sextant in the collection. I guess I get a little unnerved any time I see an instrument — which I used myself as a functional device — fall into the category of obsolete (let alone antique!).

I learned to use a sextant many years ago while I was teaching for a semester-at-sea program at a private secondary school. I remember fondly the intricacies of turning angular measurements into positions on a chart. Call me a dinosaur, but I have similar feelings about slide rules, because that’s how I learned high school physics.

Technology, by its very nature, is transient. What’s considered cutting edge will eventually be hopelessly outdated. It’s all a matter of time. As anyone who has ever purchased a computer knows, the only thing that changes is the amount of time it takes to go from “wow” to useless. For example, the sextant was a useful device for hundreds of years, but I’ll bet that if the computer that’s sitting on your desk is more than a year old, you’re thinking about buying a new one.

Diving, too, has been affected by technological change, though thankfully not to the same extent as the computer industry. One advantage of my long tenure as a diver is that I’ve witnessed many of the technological changes that have transformed our sport. A case in point: I learned to dive using a double-hose regulator and wearing a wet suit made of unlined, bare neoprene. There was no such thing as a buoyancy compensator (BC) or a submersible pressure gauge (SPG). Not having the latter created a particular dilemma, because it meant that we never really knew how much air remained in our tanks. To deal with this not-so-minor problem, a substantial amount of time during scuba training went into learning how to calculate air consumption.

I began teaching diving in 1971. Like most teachers, I modeled my behavior after those who had taught me. Therefore, at least an hour or two of every one of my courses included a thorough review of the formulas — and associated algebraic functions — that enabled divers to determine their air consumption.

Armed with this knowledge — it was assumed — divers would meticulously calculate how long their tanks would last, thus avoiding an out-of-air emergency. The reality, however, was quite different. The fact is that I never encountered one single diver — not one — who ever used this newfound mathematical capability to actually calculate how long a tank was supposed to last.

The reason it was never done was quite simple: There was no need. By the early 1970s SPGs were in common use, and calculating one’s air supply was no more necessary than calculating how much gas it would take you to drive to work and back. In both cases, all that was necessary to monitor the remaining fuel or air supply was observing a gauge. Technology has obviated the mathematical machinations.

Just as the technology of the 1970s changed the way we dove by providing a continual readout of remaining air, so too did the technology of the 1980s begin to change the way we monitored our decompression status. Microprocessors could easily be programmed with complex decompression algorithms and, in combination with depth transducers and electronic clocks, maintain a constant, real-time “pulse” on just how long we could safely remain underwater. Since then, dive computers have become increasingly sophisticated and capable of doing things never imagined 20 — or even 15 — years ago. This begs the question: Has technology sentenced the dive tables to death?

A Case for the Intensive Care Unit

It’s likely that if dive tables are ever pronounced dead, it will be after a gradual, almost unnoticed, deterioration rather than a sudden collapse. In fact, signs already exist to indicate that the patient might be past the early stage of decline. A personal observation — and one which is mirrored by many in the diving community today — is that more divers than we care to admit are about as familiar with how to use dive tables as they are with building an atom bomb.

Some have blamed the instructional community for this deficiency, pointing to everything from declining training standards to incompetent in- structors. But to me such a conclusion is simplistic, grossly unfair and shows a real lack of understanding of the modern diving experience.

While I believe a diver’s training is only as good as the instructor who taught him, I’m also certain that the vast majority of diving instructors are competent professionals who turn out competent divers. That includes their ability to use dive tables. The problem isn’t the quality of entry-level training. The problem is that, for many otherwise competent divers, the last time they may ever use a dive table is during their final exam. To understand why, one need only consider the typical scenario most divers encounter once they’re certified.

In the last decade or so there have been dramatic changes, not only in who divers are, but in how they dive. A large portion of today’s active diving population dives only occasionally, probably making less than 10 dives a year.

Logically, such infrequent divers often participate in some form of organized experience (sponsored by either a dive resort, club or dive center). This is so common today that I’d bet my snorkel that the majority of diving activity is now done under the supervision — or at least informal direction — of a professional. (I define “professional” not necessarily as someone who’s being paid, but someone who holds a certification as a divemaster or higher.)

One common characteristic of a “supervised dive” is that the dive profile is usually established by the supervisor rather than the individual divers. Particularly before the advent of dive computers, this was virtually a universal practice on any organized dive. Part of every briefing included instructions on the depth and bottom time. So even before computers factored into the formula, lots of divers spent their entire careers rarely, if ever, looking at a dive table. I believe it is this aspect of the modern diving experience, not incompetent instruction, that began the demise of dive tables.

The condition went from guarded to serious with the introduction and subsequent widespread use of dive computers.

A Coming Change in Attitudes

It’s apparent that a consensus is now building within the diving community that someday computers will sound the death knell to tables. Interestingly, this attitude seems to be consistent within a segment of our community not noted for agreement — the diver training organizations. “The time isn’t quite here for making dive table instruction optional, though it is approaching,” contends Karl Shreeves, Vice President for Technical Development for the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI). “But when the time comes, PADI will certainly support it.”

To which, Gary Clark, Director of Product Development for Scuba Schools International (SSI), echoes, “While the time is near to make dive tables optional, it’s not here quite yet.”

Jed Livingstone, Vice President for Training and Product Development for the National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), agrees, although conditionally. “When and if dive computers become as reliable and as inexpensive as a plastic dive table, it may be time to consider abandoning teaching dive tables, but we’re not there yet.” So clearly, while the handwriting may be on the wall, a bit more has to happen before we attend any funerals for dive tables.

Still, the “not-just-yet” attitude isn’t universal. Some see the time to act as right now. As proof, one need look no further than the policy of the newly formed diver training organization Sport Diving International (SDI).

According to SDI’s President, Bret Gilliam, “In developing our program, we decided to introduce tables merely as a historical reference. Although the tables’ use is demonstrated and students are required to understand the process, there’s no performance requirement that students must master the use of dive tables. Our emphasis is to teach the use of modern diving computers, which should make the diving experience more enjoyable, safer and easier.” He adds, “By emphasizing computers over tables, we recognize the reality of what’s happening among sport divers today. The reality is that dive tables are becoming relics.”

Practical Issues

One of the biggest nails yet to be pounded into the dive table coffin is getting all divers, not just most, to use dive computers. “What’s currently lacking is that computers, while virtually standard among the regular, active divers, are not universal among infrequent divers,” says Karl Shreeves. “So at present, it’s somewhat overly optimistic to think that all divers in all countries have and use them.”

Indeed, Shreeves has a point. There’s a big difference between almost everyone and everyone. And requiring divers to use dive computers — like the industry did long ago with alternate air sources — creates another concern.

“Mandating computers,” he says, “creates a new price barrier for those entering the sport. Right now tables keep computer costs from being an entry barrier. What would bridge this gap might be some very inexpensive but very reliable dive computers.” The question is, of course, whether this is possible if more people use computers. Only time will tell, but I recently bought a scientific calculator for less than 10 bucks that only a few years ago would have cost over a hundred.

Furthermore, the cost issue isn’t one that just affects consumers. Eliminating table instruction will have ramifications for both dive resorts and retailers. As Gary Clark points out, “Training and rental inventories will have to be outfitted with computers. This means an investment will need to be made by retailers and resorts, not unlike when alternate air sources were made mandatory in 1986. While unpopular in some circles at the time, it proved to be an excellent investment over the years, and I think the same thing may happen with respect to computers.”

Safety Concerns and the Human Factor

I’ve been discussing the idea of eliminating dive table instruction with dive professionals for several years, and the first objection I usually hear is: Computers are electronic devices, so what happens when they fail? Indeed, that is a concern.

However, the assumption that’s often made in this statement is that using dive tables doesn’t present a significant safety issue itself. My retort is that computers may occasionally fail, but unlike people, they don’t make mistakes. As anyone who has ever tried to learn the dive tables knows, mistakes do happen. In fact, human error is so much a part of dive tables that several mistakes were inadvertently included in early versions of the U.S. Navy tables and not even recognized until they were recalculated decades later using computers!

The human error factor is an important one to Bret Gilliam. “When I was President of Ocean Quest International, we conducted a risk management program that explored the best way to allow divers as much freedom as possible while maintaining reasonable safety parameters. The first thing we discovered was that the overwhelming majority of divers and instructors could not pass a basic repetitive dive problem worksheet using dive tables.”

He adds, “Based on this information, we began one of the first programs using dive computers. The results speak for themselves: With over 80,000 dives per year, we had not one DCS case involving a computer user. The only DCS cases we encountered involved divers using tables. There’s no question that computers proved reliable and eliminated the human error factor from table computation and record keeping.”

Still, while computers can’t make mistakes, what does happen when they stop working? To some, the solution is redundancy. Those in this camp maintain that teaching dive tables can never be eliminated until divers carry both a primary and a backup computer. But here, too, Gilliam sees the argument as spurious.

“First of all, dive computers are fantastically reliable, with a failure rate so low as to be inconsequential. Even if there is a glitch, all the diver need do is stay out of the water for 12 hours and begin anew with a backup or rental unit.”

Anecdotally, I have to concur that my experience with dive computers bears out Gilliam’s comments. I have never had a failure — nor have I witnessed one — since I began using a computer several years ago.

Yet the safety issue may not be solved as easily as Gilliam and others contend. “Some might argue that SPGs are similar to dive computers, in that when they fail you simply abort the dive,” says Bill Clendenen, Vice President of Training for Divers Alert Network (DAN). “However, unlike a scuba cylinder, which is renewed after every dive, a dive computer may carry up to a week’s or more worth of dive information before it fails. Is 12, 24 or even 48 hours enough time for complete nitrogen washout after a week’s worth of diving? Unfortunately, we just don’t know the answer.”

Muddying the water even further, Clendenen brings up the issue of accident statistics. “It’s interesting to note that DAN’s most recent accident data found that 54.9 percent of injured divers were using dive computers, 40.4 percent were using tables, and 4.7 percent used neither in planning their dives when they were injured. What’s more important than whether dive tables will continue to be taught is to ensure that divers plan their dives. Almost 5 percent of divers injured are not planning their dives with either a table or computer when they are injured.”

Some table supporters have jumped to the conclusion that the DAN data points to tables being safer than computers. But like all statistics, determining their meaning is often far more difficult than gathering the data. As the DAN report explains, “…computer users were more experienced divers, and had been diving more often and for a greater number of years than table users.” Thus, the data may just be showing the results of more frequent and aggressive diving, not the superiority of one method of dive planning over another. (See sidebar.)

It’s also important to note that current industry estimates indicate that somewhat more than half of all divers now use dive computers. Therefore, the DAN data could merely reflect the percentage of divers who are computer versus table users. The statistics may have no safety implications whatsoever.

Interestingly, a safety issue in which a significant difference between table and computer users can be found isn’t decompression sickness, but arterial gas embolism (AGE). This is an injury caused by lung overpressurization that is often associated with a rapid ascent. As the DAN report states, “About 19 percent of injured tables divers experienced AGE, compared with 7 percent of injured computer divers. One conclusion suggested by these data is that rate-of-ascent indicators on dive computers are better at keeping divers from ascending too fast than judgment methods…commonly used by divers.”

Old Attitudes Die Hard

A factor that can’t be ignored in the issue of how long tables will be with us is the attitude of instructors. After all, they’re the folks who do the teaching. Here, Gary Clark offers some interesting insights. “We sometimes forget that there’s the issue of our perception and comfort level as educators,” he contends.

“We’ve used and taught dive tables for so long that they’ve become a staple in the curriculum. To substitute them with a machine would be to some instructors like asking grade school teachers to skip multiplication tables and go straight to calculators. It just feels funny, like we’re skipping important fundamentals and not doing our job right.”

Still, Clark admits the important objective is that divers leave their training knowing how to avoid decompression problems, and for that, he says, “dive computers have proven to be an easier tool to use than tables.”

A similar opinion is offered by Clark’s colleague, SSI Training Manager Dennis Pulley, who recently conducted a survey on table/computer attitudes among SSI’s Training Advisory Committee. “Our people felt that teaching dive tables today is necessary. But as the cost of computers continues to fall, less and less time will need to be spent on the tables and more time on the use of computers, until computers are required instead of the dive tables. No one, however, advocated eliminating dive tables from the curriculum just yet.”

Exactly what impact might abandoning dive tables have on training? “I would argue,” says NAUI’s Jed Livingstone, “that the advent of the dive computer is a reason to teach more, not less. Now instructors have cause to delve deeper into ingassing and offgassing, square profiles versus multilevel diving, progressively shallower dives, responsible diving styles versus traditional recreational diving style — where you’re cramming as many dives as you can into your vacation — and all because they are now obligated to explain why a dive computer might be desirable.” This is an interesting point to consider for those who look to the elimination of dive table instruction as a way to shorten entry-level training programs.

Thumbs Up or Thumbs Down?

In the end, the future of the dive tables won’t be decided by training organizations, equipment manufacturers or industry gurus. Their fate is in the hands of the people who will or won’t use them. I believe that just as consumers sealed the fate of air consumption formulas over 20 years ago by their overwhelming acceptance of submersible pressure gauges, so too will the growing acceptance of dive computers spell the end of dive tables.

“To draw a very simple analogy,” says Bret Gilliam, “even the U.S. Naval Academy has dropped the requirement for its officers to learn celestial navigation with a sextant. Why? Because innovations in technology such as Sat-Nav and GPS have rendered sextants and sight reduction tables obsolete. Any professional mariner will confirm that GPS is more accurate, easier to work and eliminates error from either humans or atmospheric conditions. Dive computers do exactly the same thing.”

I guess I’d better save some space next to my sextant for another antique — my dive tables.

Table or Computer: Which Is Safer?

As in all controversies, advocates on either side point to their position as the right and obvious choice. But as in most partisan arguments, advocates often frame their case in a way that’s most favorable to their side.

Not surprisingly, the same thing seems to have happened in the “computer vs. table” debate.

“Computers are safer than tables!”: The key arguments in this camp invariably point to the fact that, like electronic calculators, computers preclude human error. But more than that, advocates maintain — quite correctly — that the decompression models or algorithms used by every dive computer on the market are always more conservative than the U.S. Navy Tables — and in some cases even more conservative than PADI’s Recreational Dive Planner — on a square profile.

The admonition to “follow your slowest bubbles” can’t compare to an ascent rate indicator as a safety device.