Relationships are not always what they first appear to be. And almost every adult can tell you of a “match made in heaven” that ended up in divorce court. On a happier note, how about the couple no one else sees as a good match that stays together forever? You have to look under the hood to understand the nature of a lot of relationships.

Now let’s take that thought underwater. When new divers see their first cleaning station with a small shrimp or cleaner fish scurrying around inside the mouth of a toothy grouper or moray eel, many don’t expect to see the shrimp or cleaner fish make a safe exit from what appears to be a death trap. But those safe departures happen time after time. Cleaning is a relationship that is not what it first appears to be.

The same misunderstanding often occurs the first time a diver sees tiny fishes hiding in amongst the potent tentacles of sea jellies. And what about the relationship between big sharks and the small jacks and other fishes that swarm around them? Yes, indeed, relationships between marine creatures can make you scratch your head just like those between members of our own species.

This article focuses on four relationships that divers commonly see when we are able to watch animals hunt and feed. The relationships are: competitive hunting, cooperative hunting, shadowing, and opportunistic hunting.

Upon first observation, the nature of the relationships between the creatures involved can appear to be exactly the same. But that is not the case. Understanding how these hunting relationships function and what to look for can help you experience and appreciate the world beneath the waves in a more enlightened way.

The trumpetfish will often try to hide beside a grouper or lionfish before making a sudden strike at a smaller fish, shrimp or other crustacean.

Competitive Hunting

With the exception of nursing marine mammal mothers and sea bird parents that bring food to their offspring, most marine creatures do not intentionally share food with other creatures. In many species, parents provide protection for their young before and/or after their hatching or birth, but the adults do not intentionally share their food.

In most marine scenarios, when feeding, the animal is trying to gain the nutrition it needs to survive. Sharks and other large carnivorous fishes attacking schools of baitfish illustrate this point. No sharing there! This holds true even if the predators involved are the same species, a mix of ages, sizes, sexes, or completely satiated. For marine hunters, it is all about “me getting mine.”

In addition, it is well documented in many species of carnivorous fishes, that larger animals and adults willingly prey upon the young and smaller members of their own species, including their own offspring. So not only is there no sharing, every animal has to be on guard against becoming someone else’s dinner.

Cooperative Hunting

Cooperative hunting occurs when carnivorous animals seek food together in a manner that distinguishes between the work performed by each party and the respective roles they serve. Although cooperative hunting is relatively rare in the underwater world, it does occur. The benefits are that the hunters will usually capture more prey with less effort. Additionally, the hunters’ odds of capturing more prey with less effort are greatly increased. And there are fewer “costs” involved. Those reduced costs include a lower expenditure of energy and less chance of injury.

In Hawaiian waters cooperative hunting with a peacock grouper (or several peacock groupers) and whitemouth moray eel is a common sight. Whitemouth morays and peacock groupers prey upon a variety of small fishes, crustaceans, and mollusks that often seek cover in the latticework of a reef. The eels can maneuver in and out of the tight quarters of the reef while hunting, but the groupers cannot. Conversely, groupers are adept hunters in the water column above the reef, but eels are not.

If the eel that is seeking prey in the cracks and crevices of a reef frightens its intended victim but does not successfully capture it, the flushed prey will often attempt escape by swimming up into the water column — and into the mouth of the coney.

In this relationship, the action usually starts when a hungry grouper spots an eel sticking its head out of a hole. The grouper will take up a position next to the eel and will sometimes shake its head as a way of communicating to the eel that the grouper is present and ready to get on with a hunt. In some cases the grouper will nuzzle the eel to encourage the eel to start hunting.

In other instances, a grouper will see an eel swimming across the bottom, already hunting alone. All the grouper needs to do is join in.

Once the hunt is on, if an eel that is seeking prey in the cracks and crevices of a reef frightens its intended victim but does not successfully capture it, the flushed prey will often try to escape by swimming up into the water column. That plays right into the mouth of an awaiting grouper.

The grouper might not be successful in its effort to capture the disoriented or injured prey. If that happens the frazzled prey is likely to once again seek cover in the reef. By this time the prey is a much easier mark for the eel.

By hunting cooperatively, both the grouper and the eel gain easier access to prey. But keep in mind, whichever hunter captures the prey, the food is his. There is no intentional sharing. However, any bits and pieces that drift away from the successful hunter are there for the other party, or any other creature that gets involved.

Nearly identical scenarios take place around the world. In Indo-Pacific reef communities a cooperative hunting relationship exists between day octopus and a variety of jacks. In Caribbean reef communities sea bass known as coneys routinely join spotted morays in pursuit of prey.

Whitetip reef sharks and some trevally jacks also hunt cooperatively. While the sharks usually rest during the day and hunt at night, there are times during daylight hours when jacks pursuing creolefish (and other baitfish) in mid-water cause a school of desired prey to panic and seek cover in the reef below. Sensing the panicking prey draws the sharks into action and they begin to hunt the creolefish.

Whitetips have supple, slender bodies and can get into tight quarters in reef communities where the jacks can’t go. The hunting sharks pursue disoriented and injured creolefish in the cracks, crevices, and passageways of the reef. The sharks capture some. Others return to the water column while fleeing the sharks. That is where the flushed baitfish, once again, have to contend with the jacks.

As is the case with the peacock groupers and whitemouth moray eels, the poor baitfish are caught in a dangerous situation. And they will be in that situation as long as the sharks and jacks continue to cooperatively hunt together.

In the hunting relationship known as shadow hunting, one member is carnivorous (the snapper), while the other can be herbivorous, carnivorous, omnivorous, or planktivorous (the manta ray).

Shadow Hunting

Shadow hunting involves a relationship between at least two animals that are different species. In a “two-party relationship” one member is carnivorous, while the other can be herbivorous, carnivorous, omnivorous, or planktivorous. Usually, the second party is an herbivore or planktivore, and if it is an omnivore or carnivore, it is probably not actively hunting when the shadow hunting is taking place.

In essence, the second, or non-hunting, member serves to “hide” the active hunter in much the same way a “hunting blind” helps a deer or duck hunter hide from a desired target. The theory is that the prey will not see the actively hunting carnivore because its appearance is blocked, or because the non-hunting member in the relationship is so big that the prey sees it and not the hunter. Thus, the prey is much easier for the hunter to surprise and capture during a swift attack.

Commonly seen examples include carnivorous fishes such as snapper, grouper, or jack hovering very close to a manta ray. Mantas are planktivores, and the prey of snappers, groupers, and jacks are not threatened by the ray. So, there is a tendency for small bony fishes and other forms of prey pursued by snappers, groupers, and jacks to drop their guard. And that presents a perfect opportunity for a hunter to strike.

In some instances both members of the relationship are carnivores. In those scenarios the actively hunting member uses the non-hunting partner to hide its presence. This scenario is often seen by divers when a trumpetfish uses a grouper or lionfish as its blind before making a sudden strike at a smaller fish, shrimp, or other crustacean. Successful or not, the trumpetfish will often return to its former position to try again.

The ‘Vores’

Carnivore: An animal that feeds on the flesh of other animals. Carnivores gain their energy and nutrition from a diet that consists almost exclusively of the tissues of other animals.

Herbivore: An animal that feeds on plants and algae. Herbivores gain their energy and nutrition from a diet that consists primarily on the tissues of plants, algae, and bacteria.

Omnivore: An animal that eats both the flesh of other animals, as well as, plants, and perhaps, algae and fungi.

Planktivore: An aquatic animal that feeds primarily on planktonic organisms. Those organisms can be either plant plankton (phytoplankton) or animal plankton (zooplankton). Some planktivores feed primarily on animal plankton, others on plant plankton, and many consume both animal and plant plankton. In some respects, various planktivores can also be considered to be carnivores, herbivores, and omnivores. But the size of their prey leads us to refer to them as planktivores.

In a classic example of shadow hunting, the trumpetfish uses the lionfish as a “hunting blind.”

Opportunistic Hunting

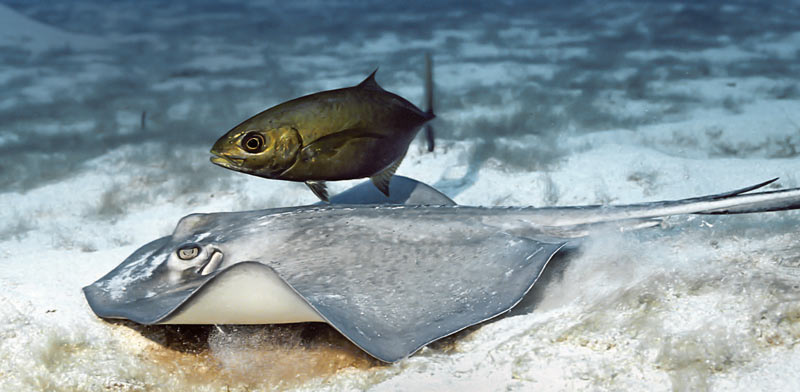

Opportunistic hunting takes place when an animal has a chance to gain access to prey because another animal or event is exposing the prey. A classic example involves bar jacks that opportunistically hunt alongside southern stingrays.

The stingrays forage for food by grubbing in the sand. Their prey consists of a mix of bivalve mollusks, worms, crabs, shrimps, echinoderms, and small fishes. A large percentage of the diet of bar jacks consists of the same food sources.

When hunting, a southern stingray often flushes a variety of creatures. The flushed animals are likely to be disoriented making them vulnerable to a fast strike by an opportunistic bar jack. The jacks are quick learners and it is quite common to see a jack rapidly take up a position directly above or to the side of the head of a hunting stingray. The stingray does not benefit from this relationship, while the jacks compete with each other for whatever prey they can capture.

Bar jacks also opportunistically hunt with yellow stingrays. Similar relationships exist between the rays and hogfish and goatfishes, as well as, between a variety of puffers that feed in the sand and numerous animals that take advantage of that activity.

That’s all we have room for here. Now, go hug and share a meal with someone you love. But don’t take your relationship for granted. Remember, relationships aren’t always as they appear.