America’s national marine sanctuaries span more than 620,000 square miles (1,605,793km2) of ocean and Great Lakes waters. They include whale migration routes, coral reef communities, spectacular shorelines and shipwrecks. Lots of shipwrecks.

More than 1,000 known and suspected shipwrecks rest on the bottom of the sea and lakes in national marine sanctuaries, a testament to our past as a seafaring nation. Afforded additional protection under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, these shipwrecks and historic sites represent one of the greatest opportunities for underwater adventure for recreational scuba diving enthusiasts.

As National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) divers and maritime archaeologists, we have logged countless hours mapping and documenting sanctuary shipwrecks to protect and preserve American history underwater for current and future visitors to enjoy. We’re often asked which wrecks are our favorites and we’re pleased to share our Top 10 “Best Of” list with you.

1. Norman

Type: Bulk freighter

Wreck length: 296 feet (90 m)

Depth: 210 feet (64 m)

Thunder Bay’s infamous fog contributed to a tragic collision in May 1895 that claimed the lives of three sailors. About seven miles (11.3 km) off Lake Huron’s Middle Island, the freighter Norman and the steamer Jack collided with enough force to cut the larger freighter almost in two.

Norman was part of a new generation of lighter, steel-constructed vessels that hauled the iron and coal that fueled the factories and growing manufacturing sites of America’s Industrial Age. On the morning of the collision, Norman was running light (empty) and likely speeding north toward the rich iron ore deposits of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula when the lumber-laden steamer, Jack, appeared out of the mist too close to be avoided. In less than three minutes, the nearly 300-foot (90 m) Norman plummeted to its current location, 210 feet (64 m) below the surface of Lake Huron in what is now Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. It wasn’t until 1986 that the shipwreck was located and work could begin archaeologically recording this intriguing piece of Great Lakes maritime heritage.

Today, one lifeboat remains at the shipwreck site, lying askew and to port of the massive freighter. Other significant features evident are the once-tall forward deck house, which lies collapsed in the mud near the port bow and the triple-expansion steam engine peeking out of the broken aft decking. Much of the below-deck area is accessible. At a 210-foot (64 m) depth with water temperature on site hovering between 38 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit (3 to 7 degrees Celsius), Norman is a challenging technical dive but well worth the effort.

A diver examines the shipwreck’s broken hull. BILL GOODWIN, NOAA/ONMS PHOTO.

2. City of Washington

Type: Steamship

Wreck Length: 325 feet (99 m)

Depth: 25 feet (7.6 m)

The SS City of Washington, a two-masted schooner rigged steamship built in 1887, served as a combination passenger and cargo transport between New York, Cuba and Mexico. In 1889, it was retrofitted with a 2,750 horsepower steam engine that dramatically increased its range and speed.

City of Washington was anchored in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898 — the night the USS Maine exploded. Burning debris from Maine damaged the ship’s deckhouse but the crew launched boats and helped rescue sailors in the water. During the Spanish-American war, the steamer sailed as a troop transport ship.

City of Washington returned to passenger and cargo duty following the war until retirement in 1908. Three years later the steamer was converted into a coal-transporting barge. While being towed by a tug, City of Washington ran aground on July 10, 1917 and was a total loss within minutes.

City of Washington now sits on Elbow Reef in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The former steamship is part of the sanctuary’s shipwreck trail, which consists of nine shipwrecks scattered from Key West to Key Largo representing America’s maritime history.

[sam_pro id=1_99 codes=”true”]

Like all of the shipwreck trail sites, City of Washington’s marine life is abundant and colorful. Its many nooks and crannies harbor lobster, eels, spotted drum and other shy creatures. Large groupers and nurse sharks hang out in the crevices in the ship’s hull, while barracuda and tarpon can be seen cruising around the shipwreck.

The shipwreck site is 325 feet (99 m) long and contains mostly the lower bilge section of the steel hull. Divers can follow the contour of the hull, although several huge gaps are present. While the site is concentrated, scattered features extend 140 feet (42.7 m) from the main axis of the ship.

A diver explores Winfield Scott’s paddle wheel. ROBERT SCHWEMMER/NOAA PHOTO.

3. Winfield Scott

Type: Side-wheel passenger steamship

Wreck Length: 225 feet (68.6 m)

Depth: 15 to 35 feet (4.6 to 10.7 m)

Off Middle Anacapa Island in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary lie the remains of the SS Winfield Scott, a 19th century side-wheel steamship that sank in 1853. Winfield Scott was one of many steamships that carried passengers and mail between Panama and San Francisco during the California Gold Rush.

Named in honor of General Winfield Scott, who was in the prime of his career when the ship was built, the ship was a four-deck, three-masted side-wheel steamer. On a cold, foggy evening in December 1853, the ship was packed with gold, mail and more than 500 passengers and crew leaving San Francisco headed to Panama. Captain Simon F. Blunt decided to take a shortcut through the Santa Barbara Channel. He confidently steered directly into Middle Anacapa Island.

The stranded passengers are believed to have lived on Anacapa Island for eight days until the side-wheel steamer California picked them up. A journal of one of the survivors, Asa Cyrus Call, is still retained by his descendants as a testament and first-person account to this moment in history.

Today, Winfield Scott’s remains lie in generally warm, clear water off the north side of Middle Anacapa. Depths where steamer’s wreckage is visible range from 15 to 35 feet (4.6 to 10.7 m). Although salvage efforts removed portions of the hull and side-lever engines, the shipwreck offers a unique opportunity to study mid-19th century ship construction and propulsion design. Divers can still see remains of the massive steam-powered machinery that once propelled the ship. Key artifacts include one of the steamer’s paddlewheel shafts with flanges, paddlewheel shaft support, paddlewheel bracing and the base of one of the piston cylinders.

RELATED READ: SWIMMING IN THE FOREST: A KELP DIVING HOW-TO

F.W. Abrams steam engine. JOSEPH HOYT/NOAA PHOTO.

4. F.W. Abrams

Type: Oil tanker

Wreck Length: 467 feet (142.3 m)

Depth: 85 feet (25.9 m)

Headed to New York City and carrying more than 90,000 barrels of crude oil, F.W. Abrams sought refuge in a minefield created to provide Allied vessels safety from German U-boats patrolling off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. On June 15, 1942, during the transit out of the minefield, the tanker lost sight of its escort in a heavy rain and made a change of course to head out to sea.

Several explosions rocked F.W. Abrams, leaving the captain and crew to believe they were under attack from a submarine. The captain ordered the crew to abandon ship and everyone was rescued and taken to Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. A Navy review of the incident concluded that F.W. Abrams had strayed into the minefield.

F.W. Abrams sits in about 85 feet (25.9 m) of water. The stern is the most visually interesting section to dive, with both port and starboard sides of the hull visible. The heavily-damaged engine still sits upright and rises almost 20 feet (6.1 m) from the bottom. Ahead of the engine are three boilers, all in their original positions nested close together. Forward of the boilers the shipwreck becomes less distinct. Wide sand breaks divide the wreck into two main sections. In 2017, NOAA partnered with the Battle of the Atlantic Research and Expedition Group (BAREG) to work with volunteer divers to conduct an archaeological survey of the site.

At the bow, divers can see the large anchor winch, chain pile and port side of the bow. The bow section normally holds a great variety of marine life as it provides a jumble of places where groupers, snappers, octopus and turtles can hide.

NOAA has proposed expanding Monitor National Marine Sanctuary to protect a collection of historically significant shipwrecks that were casualties of World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic, including F.W. Abrams. The sanctuary’s expansion would honor our nation’s rich maritime history while preserving these unique sites for maritime historians, archaeologists, curious divers and future generations.

The SB2C-1C Helldiver rests about 50 feet beneath the surface in Mā`alaea Bay, Maui. HANS VAN TILBURG/NOAA JOSEPH HOYT/NOAA PHOTO.

5. Curtiss SB2C Helldiver

Type: Military aircraft

Wreck Length: 37 feet (11.3 m)

Depth: 50 feet (15.2 m)

Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary is well-known for the animals it protects. Each winter, roughly 12,000 humpback whales visit its waters to mate, give birth and raise their calves. But in the ocean surrounding the main eight Hawaiian Islands, curious divers can also find traces of our nation’s military history. During World War II, more than 1,000 aircraft were lost in Hawaii. Some of these, including a Curtiss SB2C Helldiver off the coast of Maui, can be explored by recreational divers.

On August 31, 1944, pilot William E. Dill and radioman Kenneth W. Jobe, members of patrol bomber squadron VB-4, were conducting dive-bombing practice offshore of Maui with their squadron. After completing their second steep dive on the target and while doing high-speed evasive maneuvers, the entire vertical stabilizer assembly twisted to port, jamming the rudder controls. Lt. Dill, no longer able to safely control the aircraft, made a voluntary forced landing in the water a few miles south of Puunene Naval Air Station. The pilot and radioman were rescued, but the plane was never recovered.

In January 2010, Maui dive shop owner Brad Varney heard about a two-seat dive bomber in about 50 feet (15.2 m) of water in Mā`alaea Bay, Maui. With the help of the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, NOAA and local divers, the plane was identified as a World War II SB2C-1C Helldiver. The bureau number stenciled on the broken tail section — which lies in the sand near the aircraft — confirmed that the plane is Dill and Jobe’s.

Divers can see the plane almost exactly as Dill and Jobe abandoned it. The landing gear is retracted, the leading edge flaps are up and the wing flaps are down. The canopy is open and the large life raft storage tube in the gunner’s position is empty. The wreck also serves as a habitat for Hawaiian marine life, with corals and other invertebrates growing on the fuselage and fish flocking to it for shelter.

The E.B. Allen sits 100 feet below the surface on an even keel. NOAA PHOTO.

6. E. B. Allen

Type: Canal schooner

Wreck Length: 134 feet (40.1 m)

Depth: 100 feet (30.5 m)

After the Erie Canal opened in 1825, thousands of farmers settled in the Midwest, transforming the region into the nation’s breadbasket. Moving grain to national and worldwide markets took a huge number of specialized ships, many like the E.B. Allen.

Shorter and narrower than the locks they had to navigate, the boxy-hulled schooners maximized their payloads on every trip, carrying grain eastward and coal westward. On its last voyage in November 1871, E.B. Allen was bound for Buffalo, New York, carrying a cargo of grain when it collided in heavy fog with the sailing vessel Newsboy , which tore a large hole into E.B. Allen’s port side.

As the ship began to sink about two miles southeast of Thunder Bay Island, Allen’s crew was taken aboard the Newsboy. Now resting upright in 100 feet (30.5 m) of water in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and seasonally marked with a NOAA sanctuary mooring buoy, E.B. Allen is a popular dive site and among the best-preserved 19th century sailing ships in the Great Lakes.

Although the masts are broken and most of the deck planking gone, the windlass, anchor chains and rudder are still in place. Divers can swim below decks for a view of the massive centerboard trunk containing the centerboard that, when lowered below the vessel while sailing, helped it maintain a straight course in contrary winds. Folding catheads (used to secure the anchor once it was raised) can be seen at the bow and at the stern divers can spot the vessel’s rudder post and glimpse construction features exposed by the missing cabin. Amidships on the port side is dramatic evidence of the Allen’s fateful collision.

7. USS Monitor

Type: Navy ship

Wreck Length: 179 feet (54.6 m)

Depth: 230 feet (70.1 m)

Many divers are often surprised to learn that they can explore the resting place of the Civil War ironclad USS Monitor, which ushered the modern era of naval warfare and became the focal point of our nation’s first national marine sanctuary on January 30, 1975. Today, the shipwreck rests about 230 feet (70.1 m) below the ocean surface near Cape Hatteras. All it takes to dive the shipwreck site is a free permit and the technical skill to navigate strong currents and often adverse weather conditions.

Despite the challenges, the experience that awaits experienced tech divers is unforgettable. The shipwreck offers a window into the past, giving divers a unique glimpse at the Civil War and our nation’s naval heritage. Divers often express that at first sight of Monitor, they experience an overwhelming sense of reverence for the ship and its place in history. As they explore the shipwreck from bow to stern, the natural beauty surrounding the wreck awes them.

From the surface to the bottom, the sanctuary experiences seasonal migrations of cetaceans, sea turtles and fishes, including sharks and manta rays. Crabs, brittle stars, sea urchins, sea anemones, tube worms, oysters and a host of other organisms blanket Monitor’s hull.

Divers exploring the shipwreck can see the ironclad’s massive armor belt, still intact after more than 150 years on the seafloor. Schools of amberjacks hunting baitfish that hide within the ship itself surround the ship’s massive iron frames. Iron plates that once repelled cannon fire host corals and sponges. The ship that saved the Union is now an oasis of life on the seafloor.

8. Hannah M. Bell

Type: Cargo ship

Wreck Length: 315 feet (96 m)

Depth: 10 to 30 feet (3.1 m to 9.1 m)

Hannah M. Bell was a 315-foot (96 m) British steel-hulled steamship named for the woman who christened it. Prior to its demise, the ship made frequent transatlantic trips between European ports, the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts and Caribbean and South American ports. It transported a variety of bulk cargos including cotton, sugar and coal.

On April 4, 1911, Hannah M. Bell grounded during a storm about six miles offshore of Key Largo, Florida. With the ship’s engine room flooded and holds filled with water, salvagers dispatched the wrecking tug Roosevelt to the scene. Before the tug arrived, however, the captain abandoned the vessel, as heavy weather tore the ship apart. Fortunately, no lives were lost.

Today, the wreck rests in 10 to 30 feet (3.1 m to 9.1 m) of water in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. For years, it was known as “Mike’s Wreck,” after a local dive center employee. In 2012, NOAA researchers and volunteers from Diving with a Purpose, a maritime archaeology nonprofit, identified the wreck.

While storms and salvage have taken their toll on Hannah M. Bell, the wreck remains an impressive site. Portions of its hull rise from the seafloor as much as 15 feet (4.6 m). Divers can also see large elkhorn corals while swimming around the adjacent reef.

A mooring buoy near the wreck makes it easy to dive on Hannah M. Bell without damaging it or the surrounding reef. The Keys have used mooring buoys since 1981 as an alternative to anchoring, which can break and damage the coral reef. Beyond those near Hannah M. Bell, nearly 500 mooring buoys are available for free throughout the sanctuary on a first-come, first-served basis.

Patriot lies partially-buried in the sandy seafloor of Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. MATTHEW LAWRENCE/NOAA PHOTO.

9. F/V Patriot

Type: Western rig dragger

Wreck Length: 62 feet (18.9 m)

Depth: 100 feet (30 m)

Originally constructed as a shrimper, the F/V Patriot rests in 100 feet (30.1 m) of water in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. Patriot fished in Massachusetts Bay until January 3, 2009, when disaster struck.

After the Patriot hauled in its nets following a tow, it suddenly capsized. The two crew members aboard were unable to escape the sinking vessel and drowned. Ultimately, a Coast Guard investigation found that modifications to the vessel had altered its stability, making it susceptible to being swamped in heavy seas.

Today, the red-and-black-hulled Patriot lies on its starboard side on a flat sandy bottom atop Stellwagen Bank. The shipwreck attracts schools of cod, red hake and Atlantic torpedo rays. Even more spectacularly, some divers have seen humpback whales underwater while diving the Patriot.

Winter storms in 2012 tumbled Patriot 900 feet (274 m) across the seafloor, breaking off its mast and outriggers and leaving it partially buried in Stellwagen Bank’s sandy seafloor.

Before diving, check the sanctuary’s marine forecast and offshore weather buoy reports as the sanctuary’s exposed waters can create challenging conditions. Thermal protection for the sanctuary’s cold waters also is recommended.

Be on the lookout for entangling fishing nets and other gear hanging from the wreck. Fortunately, visibility in the sanctuary is usually in excess of 20 feet (6 m), allowing this gear to be spotted and avoided.

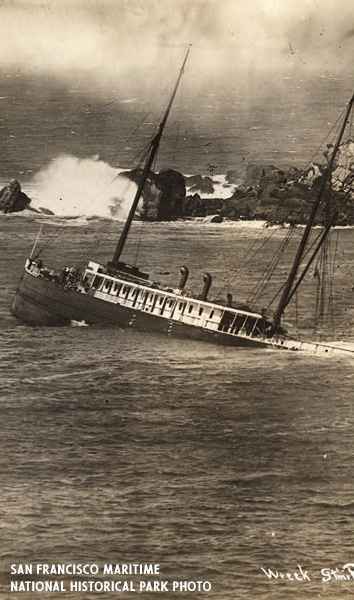

The SS Pomona being salvaged by the steam schooner Greenwood. SAN FRANCISCO MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK PHOTO.

10. Pomona

Type: Passenger steamship

Wreck Length: 225 feet (68.6 m)

Depth: 27 to 40 feet (8.2 to 12.2 m)

Built in San Francisco in 1888, the 225-foot (68.6 m) long SS Pomona is one of the most accessible shipwrecks in Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. Pomona was a state-of-the-art passenger steamship that sank after hitting a submerged pinnacle and now lies in 27 to 40 (8.2 to 12.2 m) feet of water in Fort Ross Cove.

Pomona featured a strong steel hull, a luxurious white deckhouse, two sturdy black masts and a fashionable, imposing vertical cutwater. It was also the first Pacific coast passenger vessel fitted with a triple expansion steam engine. Soon after entering service, Pomona earned the nickname, “the Pride of the Coaster Fleet.”

On the evening of March 17, 1908, Pomona struck a submerged rock south of Fort Ross as it traveled from San Francisco to Eureka. Seeking to prevent significant loss of life, Captain Charles Swansen steamed into Fort Ross Cove hoping to ground the vessel on its sandy beach. Rather than reaching the beach, Pomona grounded on a second rock where it remains today. There was no loss of life and salvage efforts managed to save most of its cargo.

Pomona, which is also located within the boundaries of the Fort Ross State Historic Park, is an excellent example of a steel-hulled propeller-driven coastal steamship that carried freight and passengers. Its hull lists to starboard and points toward the cove’s mouth, having been spun around by waves after the final impact. Although the bow has separated from the rest of the hull, it remains intact and includes the two hawse holes, a hatch cover and portions of the superstructure.

Divers exploring its steel hull can trace its original shape, as well as the starboard scotch boiler, near its original location amidships. Salvage and wave action have moved the port-side boiler past the stern. Around the shipwreck site, divers will also see large I-beams and sections of the masts.

Divers have been visiting the site since the 1908 sinking. That very year, the San Francisco Chronicle published a story about a salvage diver who engaged in combat with a “devilfish,” probably an octopus. In 2016, NOAA and California State Parks conducted monitoring dives on the site to access its condition and gather imagery for outreach initiatives as part of a more extensive Doghole Ports Project. This work was part of an ongoing partnership to interpret the region’s maritime cultural landscape.

For more information on diving these and other sites in the National Marine Sanctuaries, visit sanctuaries.noaa.gov/diving/.

Tips for Shipwreck Diving in the National Marine Sanctuaries

Learn the rules. Prior to diving in a national marine sanctuary, familiarize yourself with the specific rules and regulations within its boundaries. Visit each sanctuary’s website to learn more.

Respect marine wildlife. Several sanctuaries have specific regulations prohibiting harassment or take of marine animals. Enjoy viewing marine wildlife from a safe distance.

Learn the proper techniques for shipwreck diving. When diving shipwrecks always know the orientation of the wreck site and only penetrate the wreck if specifically trained and equipped to do so. In addition, learn the proper wreck diving protocols in order to minimize impacts to cultural resources.

Sharpen your skills. Mastering buoyancy control and streamlining your equipment will help minimize the risk of entanglement or accidental disturbance of the bottom, which can harm the environment and historical artifacts. Even the slightest damage can permanently alter an entire ecosystem or historical shipwreck site.

RELATED: SCUBA SKILLS AND VIDEOS

Don’t collect underwater souvenirs. Collection of natural and cultural items is regulated in sanctuaries and often is prohibited or requires a permit. Resist the temptation to collect shells, rocks or other underwater artifacts, because they provide homes for sea creatures and good surfaces for plants and animals.

Be a marine debris crusader. Carry away any trash you find. More than just an unsightly nuisance, litter poses a significant threat to the health and survival of marine organisms.

The authors wish to thank the following NOAA colleagues for assistance with this article: Shannon Ricles, Hayden Sloan, Vernon Smith, Oren Lieber-Kotz and Elizabeth Weinberg.