It was a simple plan. A youth soccer team and their assistant coach, as part of a birthday celebration for one of the boys, would go for a short hike into a well-known cave. The plan was to be at the cave for no more than an hour. Family, friends, a Sponge Bob Squarepants cake and presents were waiting at the birthday boy’s home.

But plans do not always go according to plan. The Thai youth soccer team, nicknamed the Wild Boars, became the focus of worldwide media attention after the boys, ages 11 to 16, and their 25-year-old coach, failed to return from the Tham Luang Nang Non caves. All that remained of the team were bicycles and packs outside the cave entrance and some handprints, bags and sandals inside the complex. The date was Saturday, June 23.

The international search effort for the boys and their coach by military and search and rescue personnel, including rescue cave divers, dominated news feeds. Rescue teams started pumping water from the caves and spelunkers looked for new, natural openings into the caverns. Ten days after their ordeal began, two British search and rescue cave divers found the team on Monday, July 2. The coach had guided the boys to a high ledge two and a half miles inside the cave to escape rising floodwaters. All were alive but malnourished.

It was now a full-fledged rescue operation. Divers brought in food and other supplies while rescuers scrambled to determine the best options to get the boys out. Diving medical personnel also participated, assessing and treating the boys. As concerns about monsoon rains and flooding increased, getting the boys out sooner rather than later in a daring dive rescue was the option that was chosen. This was technical cave diving and caving under extremely dangerous conditions.

Rescue preparations would take another week. A decision was made to begin the rescue, bringing the boys out four at a time, medicated with sedatives and strapped on gurneys, wearing full-face mask underwater breathing apparatus.

The daring planned worked. On Thursday, July 10, the last four boys and their coach were safely removed from the cave. It was extraordinary news and the world rejoiced, marveling at the dedication, expertise and bravery of the Thai and international rescue divers, diving medical personnel and their support teams. We also collectively mourned the loss of volunteer rescue diver Lieutenant Commander Saman Kunan, a former Thai Navy Seal, who died in the cave complex during a mission to deliver oxygen.

Meanwhile, at Home

As the Thai rescue drama unfolded on our news feeds, my husband, Eric Hanauer, and I were preparing for a dive trip to one of our favorite destinations. We had been out of the water for a year, the result of life happenings that kept us busy at home: the hospice care and passing of an elderly parent, a planned surgery that could no longer be put off and completion of an exciting book project. We finally had the time and energy to do what we love, go diving.

We, too, had a simple plan. We didn’t want to travel too far from home and wanted to go to familiar, warm waters. Once there, we wanted to do an easy first dive as we got used to our gear again, making adjustments to our equipment and cameras. We booked flights, a cat-sitter, a car and a condo.

But within 36 hours of landing at our destination, where we had planned to make a first “simple” dive to check gear, we, like the Thai cave boys, became lost. Just as their simple hike of an hour had gone completely off plan, so had our “simple” checkout dive. A chain of circumstances plus unforeseeable and unusual conditions resulted in us and four other divers becoming lost from our boat and its captain.

Pre-trip Preparations

Upon arriving at our destination, we decided not to dive on the first full day of our holiday. We wanted to adjust to the time difference, get settled in the condo and organize gear. The first full day we assembled camera housings, lights and arms and repacked gear into mesh boat bags, double-checking everything. I needed a clip to secure my new Dive Alert deluxe surface marker buoy, also known as an SMB or safety sausage, to my buoyancy compensator (BC). My new safety sausage was nearly twice the size of my old one, a few inches shy of six feet tall and eight inches wide.

I had seen one of the “super” safety sausages while diving with a friend in Honduras. It looked a little big and bulky dangling from her BC, but it also looked sturdy and the colors were eye-popping rescue yellow and orange, plus reflective tape on the top. It would be a hard to miss this bad boy when deployed. I bought one soon after returning home from Honduras. My husband named it the “super” safety sausage for its size. I purchased one for him, too. But for our trip, he brought along his older, smaller safety sausage.

We also needed batteries for our new Nautilus Lifeline GPS personal locator beacons, PLBs for short. In the rush leaving home, we had not yet purchased batteries and I also wanted a lanyard for the device. We reviewed operating instructions and I practiced turning it on and pushing the test light. I wanted to see if I could operate the device wearing dive gloves. Everything tested fine. But during final packing back home in California, Eric decided to leave his PLB behind.

We went to the dive shop the first evening to book dives. I bought a BC clip for my “super” safety sausage, the PLB battery and a lanyard to secure the PLB inside a BC pocket. We booked on a big boat that included beginning divers. No problem with us; our plan was to make an easy dive after our long hiatus from the water.

That evening the shop called and suggested we switch to a less crowded boat, a smaller six-pack. This boat was for more experienced divers and the faster boat went further afield. Eric preferred the six-pack option: I preferred the big boat to make a “walk in the park” dive first. We ended up on the six-pack. After all, Eric has been diving for 60 years and stopped counting dives after 5,000 and I have been diving 45 years. I never counted, but estimated 2,000 dives in a career that included teaching scuba diving for 10 years and working as a field producer on underwater documentaries for television. Eric ran the scuba program at California State University, Fullerton for 35 years, certifying more than 2,000 divers. Both of us are retired L.A. County, NAUI and PADI scuba instructors.

With the Flow

Our first diving day dawned. We set off in the six-pack, getting a boat procedures briefing from the divemaster. After a pleasant ride north, we came to the mooring location for our first dive. A big boat, just getting its load of divers into the water, was already tied up at the spot our dive master had planned to use. Rather than tying up to the big boat and jumping in with other divers, he suggested that we try another spot farther north, a drift dive known for a manta cleaning station. We all said okay, although I felt uneasy about the change of plans.

The suggestion and agreement to go to another site and do an unmoored dive, drifting with the boat following us, set in motion an unlikely chain of events that would lead to six experienced divers becoming lost from their dive boat and swept out to sea in a swift blue-water current.

As we motored north, I said to Eric that I did not consider a drift dive to be an easy “walk in the park” dive on which to sort our gear after a year out of the water. With reservations on my part, we continued north and began suiting up. The five divers and divemaster needed to be ready at the same time, dropping into the water in pairs and regrouping on the bottom. Eric had not planned to take a camera on his first dive, but when he heard the magical words “manta cleaning station,” I knew he was taking his video camera and new lights, no matter what. I took my smaller still rig with strobes.

RELATED READ: DRIFT DIVING: HOW TO USE CURRENT TO YOUR ADVANTAGE

The plan was to drift south, with the prevailing south swell, current and wind. But after we were grouped on the bottom at 45 feet (13.7 m), the divemaster realized the current there was moving north. He returned to the surface to tell the skipper that we were heading north. Away we went, riding a pleasant current over sand channels and coral reef mounds, keeping our eyes peeled for a possible manta. Our depth did not exceed 45 feet (13.7) and visibility was about 80 feet (24.4 m). The current moved us parallel to the shore and we could hear the boat overhead, following our bubbles.

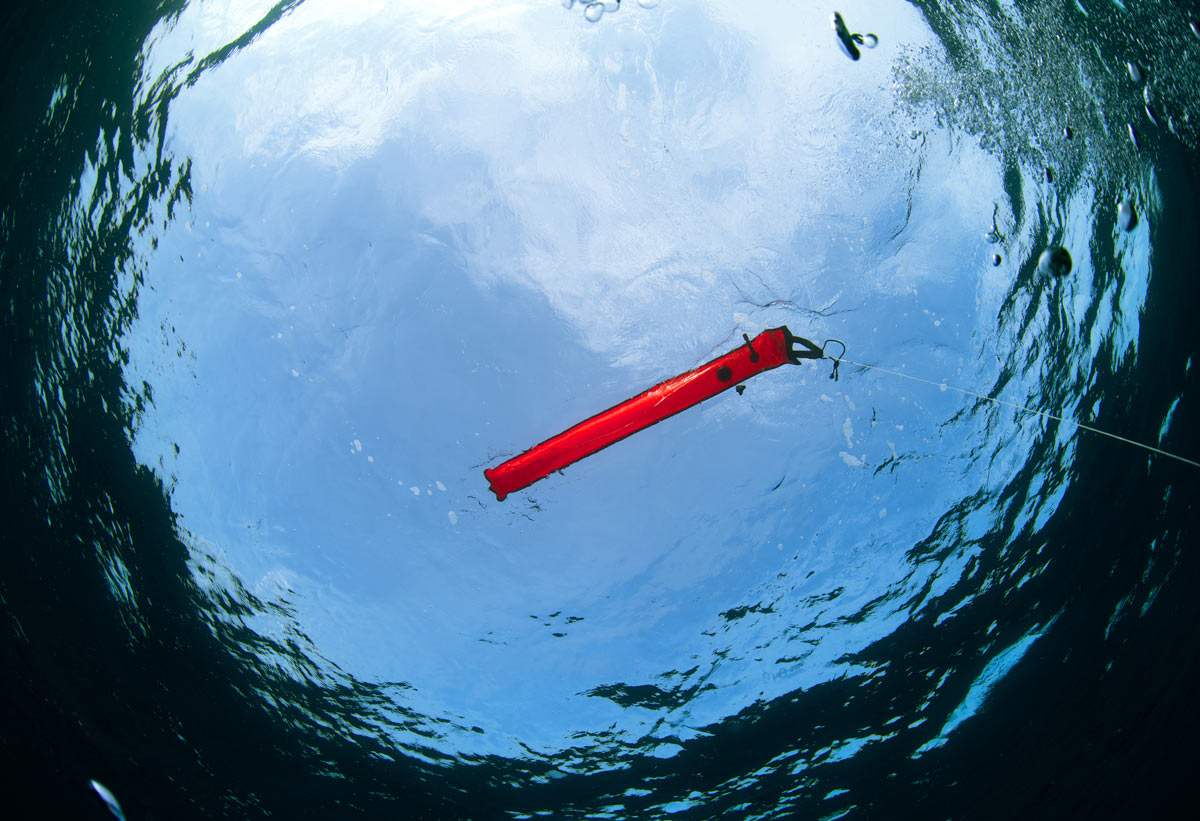

About half way through the dive, conditions changed. Visibility improved and the current picked up. We were soon blowing along sideways. It was a fun ride, but impossible to take pictures. You simply couldn’t stop. Towards the end of the dive Eric filmed a sequence of the divemaster deploying the surface marker on a reel. Then he and another diver headed up for their 15-foot (4.6 m) safety stop. I stayed between the ascending divers and the three still on the bottom, taking a moment to snap a still of the deployment of the surface marker. Then I headed up for my safety stop. The divemaster and the two others remained on the bottom for a couple of minutes and then headed up. From our stop at 15 feet (4.6 m), we could see the last three ascending, following the surface marker line. Once we hit the surface, things were no longer so easy and our simple dive plan had gone badly awry.

GETTY IMAGES

Like a Bad Movie

On the surface, we ended up in two groups of three. Looking around, we did not see a dive boat. The divemaster had used a safety sausage on a reel for the surface marker. The rest of us soon deployed our own safety sausages, for a total of four SMBs among the six of us. After deployment it became obvious that we were no longer moving parallel to the shore: we were moving swiftly away from the shore, being swept north into deep blue water with big rolling swells and surface chop. The wind had picked up and it was challenging to keep the safety sausages upright and not bent over in the wind and swells. (For more on safety sausages, see the sidebar, “Get to Know Your Safety Sausage.”)

After inflating BCs and deploying safety sausages, I told my group that I had an EPIRB. More accurately, I had a personal location beacon, a PLB. By this point, with still no boat in sight, I didn’t care what it was as long as it worked. (To learn the difference between the two devices, see the sidebar, “EPIRB or PLB?”).

Eric was urging us to join the divemaster’s group, saying it was important to keep everyone together. We heard a shout from the divemaster, but could not hear what he said. We took it to mean “Group up, everybody stay together.” Swimming on our backs with inflated BCs, we made our way to the other group, one hard kick at a time. We made it, leg muscles feeling the strain. I kept my mask on, trying not to swallow seawater from the irregular chop. I also had a snorkel, but did not use it. I told the divemaster that I had a locator beacon. After a group discussion, it was agreed that we would continue to wait for our boat, any boat, and not yet deploy the PLB.

Our divemaster asked us to swim towards shore, hoping to move us out of the relentless blue-water current and large swells. Eric, a former competitive swimming coach, did not think there was any chance of reaching shore, which was now a mile or more distant, against the current. We swam as best we could, staying together. There was some discussion of ditching weights but we didn’t actually do it. If we had ditched the weights the soft pocket weight belts Eric and I wore could loop together for the divers to put their arms through, making it easier to stay together.

We had now been drifting in the current and swells for more than 40 minutes. No sign of our dive boat, but as swells lifted us up we could see a big charter boat between the shore and us. It seemed pointed in our direction. We shouted, blew whistles and waved inflated safety sausages as high in the air as we could. When the boat drew closer I deployed the Dive Alert pneumatic signaling device attached to my BC power inflator, loosing an ear-piercing signal with an audible range reputed to be up to one mile. But rather than investigating and asking if we needed assistance, the boat appeared to take a look, then veered off towards home port. We could not be positive that the boat saw us, but we sure felt like it did.

RELATED READ: SIGNALING DEVICES FOR SCUBA DIVERS

We learned later that two boats did see us, but did not think that we were in trouble. I can only surmise that those two captains assumed our dive boat would find us. As the charter boat motored away, we had another group discussion about our options. Our divemaster’s primary concern was that were being swept farther out into open ocean, reducing the likelihood of encounters with any boats. Plus, it was getting harder to spot us in big rolling swells, chop and wind. We had now been drifting for more than 45 minutes.

Pulling the Trigger

To us, the lost divers, the obvious option was to deploy the PLB. But it was a decision that we did not want to make lightly, appreciating the repercussions. We knew that pushing the button would launch an air-sea rescue effort and we’d been holding out hope that our dive boat would locate us “in a few more minutes.” Finally, as a group, and with the divemaster’s agreement, we decided it was time to deploy the last device we had in our safety arsenal. While the other divers assisted by holding my camera and helping manage my safety sausage, I removed the PLB from my BC pocket, making sure that the lanyard was still attached. Raising the device, which is about the size of a pack of cards, I unlatched and flipped back the cover, removed a second safety cover, deployed the antenna and turned the device on. With everyone watching, I asked if we were ready to push the red emergency button. Everyone nodded yes and I pressed the button. A reassuring red light started blinking, indicating that the device was working. Our distress signal was pinging on the screens of emergency services personnel and now our group was officially more than misplaced: we were officially the target of an ocean search and rescue mission.

RELATED READ: HOW TO DEPLOY AND USE A LIFT BAG

Wait Mode

Like the Thai cave boys, we were now in wait mode, not knowing how long that wait might be. I held the PLB as high as I could in my left hand, keeping the antenna up in the air and not allowing it to dip under the swells.

The Thai cave boys waited 10 long, frightening days in the dark: wet, cold and starving, not knowing if searchers would ever find them. They used meditation techniques taught to them by their coach to conserve energy and remain calm. We were fortunate, relieved and grateful that we waited only about 30 minutes before we saw a big boat approaching from the direction of the shore. It was a charter day boat with snorkelers and other passengers enjoying a sunny day on the water. As the boat pulled alongside us, I looked up to see passengers hanging over the railing, cell phones filming the rescue. I shouted, “Which way to San Diego?” which got a laugh.

The crew tossed us an orange safety ring on a long line. Gratefully, we grabbed the ring and the line and were pulled in to the stern of the boat. Crew took our cameras and fins, then helped us scramble up the bucking and pitching ladder to the swim step. Once up on the back deck we dropped tanks, BCs, weights, regulators and masks in a jumbled, wet pile. Crewmembers immediately brought us ice-cold bottles of water. Fresh water never tasted so sweet and so good.

A crewmember pointed at my six-foot yellow-and-orange safety sausage, twisted in among the pile of black dive gear. “That’s how we found you,” he said. “It was that big safety sausage. That was the only thing we could see in the swells.”

My SMB Soapbox

By now you’re getting the message that the SMB is an important safety accessory. Deploying it correctly takes a bit of practice, so here are a few more tips:

- Ask the pros at your dive center to go over the various features and benefits of SMBs and line/reels and help you select the items that best suit your diving locales.

- Go big. Invest in the biggest, tallest, brightest SMB you can find.

- Practice using the float and line/reel in a pool or in a protected area first, so you can get comfortable deploying it before attempting to do so in a strong current or challenging seas.

BARRY GUIMBELLOT PHOTO

- Keep your SMB clipped to your BC or stowed in a BC pocket for easy access and carry a reel with at least 30 feet (9 m) of line attached.

GUI GARCIA PHOTO

Remain close to your dive buddy and take turns helping each other launch your SMBs. And remember, it’s always best for each diver to have his or her own buoy.

- Deploy the safety sausage while at a shallow depth, before you start your safety stop. This helps the boat spot you before you reach the surface.

- Before inflating the tube, make sure the attached line isn’t tangled in either your gear or your buddy’s.

BARRY GUIMBELLOT PHOTO

- Only partially inflate the SMB while at depth. Do not attempt to fully inflate it as this could cause you to accidentally exceed a safe rate of ascent. Fully inflate it once at the surface.

- Reel in the line as you surface. This helps you avoid entanglement.

- When you reach the surface, do a quick 360-degree look around to check for boat traffic. Next, fully inflate your BC and then add more air to the SMB, if necessary, to fully inflate it.

Search and Rescue: Getting Found

The boat that found us had been alerted by our dive boat captain and the dive operator that divers were missing. The day boat usually cruised closer to shore and not so far north. But with word out about missing divers drifting north, it diverted from its course to help with the search. The rescue boat was also receiving our SOS distress signal from the PLB, as were other boats and the authorities on shore. (Our distress signal range was 35 miles.) About 10 minutes after boarding the rescue boat, our dive boat pulled up. Then two rescue helicopters arrived, hovering overhead. The boat captains radioed that the missing divers were found, rescued and okay.

It was decided that we should return to our boat. Sea conditions were too rough to allow the boats to raft up, so we would have to swim between the two boats. We put our gear back on. Our boat skipper tossed in a life ring on a current line. One by one we jumped in and were towed/ swam back to the dive boat. Once again we climbed a bucking ladder onto a swim step. The helicopters peeled off back to shore as we completed the transfer.

It was a quiet and reflective group as we headed back to port. Asked if we wanted to make our second dive, there was a firm “No thanks!” We had already made one dive and agreed that the open-water surface drift of more than an hour waiting for a boat counted as our second dive.

What Went Wrong

In 37 years of running a dive operation, our dive operator had never lost track of divers. The separation from our boat did not occur because the crew was inexperienced or inattentive. We could hear the boat overhead following our bubbles north. What could not be anticipated were the sea conditions that changed about halfway through the dive, resulting in the bubbles of six divers disappearing from view on the surface.

In retrospect, two things happened that day. First, Eric and I got caught up in a series of events that resulted in us ending up on a more advanced drift dive instead of the planned “walk in the park” dive. The second thing that happened was all six divers started the dive in manageable sea conditions, but finished the dive in unmanageable sea conditions. These swiftly changing ocean conditions resulted in an incident that no one could have foreseen.

Our dive operator said the conditions we encountered that day had never been seen before in that area. There is speculation that conditions changed so rapidly because of ongoing seismic events at our vacation destination. The southerly swell and rising winds combined with a ripping northerly current resulted in a mini “perfect storm” that made the divers invisible from the surface. By the time the surface marker was deployed for our ascent, we were already well separated from the boat, having gone much farther north than was anticipated or even imagined. Once on the surface, large swells, chop and wind spray made us all but invisible to boats.

What Went Right

But in the end, like the soccer team trapped in the cave, a lot of things went right for us after becoming lost. The boys in the cave stayed together, as did our group of divers. And like the boys, we remained calm. Our incident reinforces how important it is to buddy dive and to stay together as a group during drift or current dives. Had we surfaced separately and not stayed together, the outcome could have been much different. Among the six divers, there was only one personal locator beacon and only one safety sausage firm enough to remain upright in the wind and tall enough to be spotted among the swells.

I am also impressed with and grateful for the standardized training that we as divers receive. Six divers who did not know each other (except for me and Eric) formed a team who shared ideas and worked on solutions together. Everyone remained supportive and focused. It was also a comfort knowing that an experienced, local divemaster was with us, assessing deteriorating sea conditions, noting how far we were drifting from shore, keeping track of where the current was taking us. He had the knowledge of local waters to understand that chances were rapidly dwindling for an encounter with any boat. He knew better than any of us when the trigger needed to be pulled.

We also had and still have confidence and trust in our dive operator, divemasters and boat captains. They also greatly contributed to stuff going right for us: notifying authorities and other boats promptly, asking for assistance with the search and searching relentlessly for us. After the rescue, our dive operator interviewed everyone, divers and crew, establishing facts and asking what could be learned or improved from the experience. He also planned to speak to the two boat operators who saw us in the water and did not stop to ask if we needed assistance. We made the rest of our dives with the same operator, divemasters, boats and captains.

We are divers — we love a sport that has awesome rewards. Eric and I will never forget spending a couple of days diving with humpback whales, a mother, calf and escort. Or interacting with dolphins, sea lions and manatees; witnessing the silent majesty of a great white shark or giggling as an improbably polka-dotted whale shark glides past.

But these incredible rewards go hand in hand with heightened risks. Being in, on, around and underwater and with boats increases the potential for things going wrong. The best we can do is to be prepared with proper training, using reputable, professional and experienced dive operators; having and knowing how to operate safety and emergency equipment, reacting appropriately and calmly in emergency situations and knowing our personal limitations.

Each diver should be equipped with an inflatable surface marker buoy, or SMB.

In Hindsight…

Yes, hindsight is always 20/20. With that in mind, here are some insights into hindsights, to think about next time you prepare to go diving.

In hindsight, I wish I had spoken up about being uncomfortable doing a drift dive for our first dive after a year out of the water. I might not have been very popular on the boat (or with Eric!) for speaking up, but it would have been better to be unpopular instead of having to be rescued (or worse). Speak up. Know your limitations. Listen to your inner voice. The bottom line is that you are responsible for yourself and your safety. Don’t just go along with the group if you feel uncomfortable or something doesn’t feel right. We had a simple plan (easy dive first, no cameras) and we did not stick with the plan.

In hindsight, EVERY diver should carry his or her own a brightly colored, large safety sausage, air-powered signaling device and a PLB device, especially on drift, boat or current dives. A couple of us also carried whistles on our BCs, but these did not seem to make much noise above the wind and waves.

In hindsight, perhaps it should be standard practice to use a surface marker throughout drift or current dives. Also, a bigger, brighter-colored surface marker that stays more upright in the water in swells, chop and wind would be an added safety factor.

In hindsight, I’m really glad that I surfaced from the dive with a good supply of air, 1,000 psi (69 bar). I needed air on the surface to keep my BC fully inflated, to operate my Dive Alert pneumatic signaling device and to inflate and then keep stiffly inflated my large safety sausage, so wind and swells did not bend it over, making it less visible to rescuers.

In hindsight, it would have been helpful to ditch our weights. There’s no need for having nagging thoughts about “throwing good gear away.” Weights are easy to replace.

In hindsight, non-diving boat operators need to be more aware of safety sausages. Most importantly, they need to be able to assess if a safety sausage is being deployed routinely in a known diving area as a surface marker OR if it has been deployed in an emergency situation. Six divers drifting in deep blue water offshore in big swells, chop and wind was not “routine,” and the two boats that spotted us should have investigated and asked if we needed assistance, rather than motoring off, assuming our dive boat would find us. As a boat skipper once told me, ASSUME stands for “making an ASS out of U and ME.” Never assume anything, especially in, on, around or underwater the water.

Epilogue

The day after our rescue we took a rest day to let tired muscles recover.

We finally made our “walk in the park” dive with no equipment problems and no drama.

We emailed our friend who developed our PLB device and thanked him profusely for designing one specifically for divers.

I thanked my Honduras diving buddy for recommending her “super” safety sausage to me.

We gained something of a reputation at the dive shop and on the dive boats: “It’s you guys, the no-boat drift divers!”

Our kids even took a shot, a daughter texting, “Hey, aren’t WE supposed to be giving YOU guys the grays hairs, not the other way around?”

Our final dive of the trip was a blackwater drift dive to see pelagic creatures at night. Our dive operator got in the last shot as we boarded: “Damn, I’m glad you two will be tied to the boat tonight!”