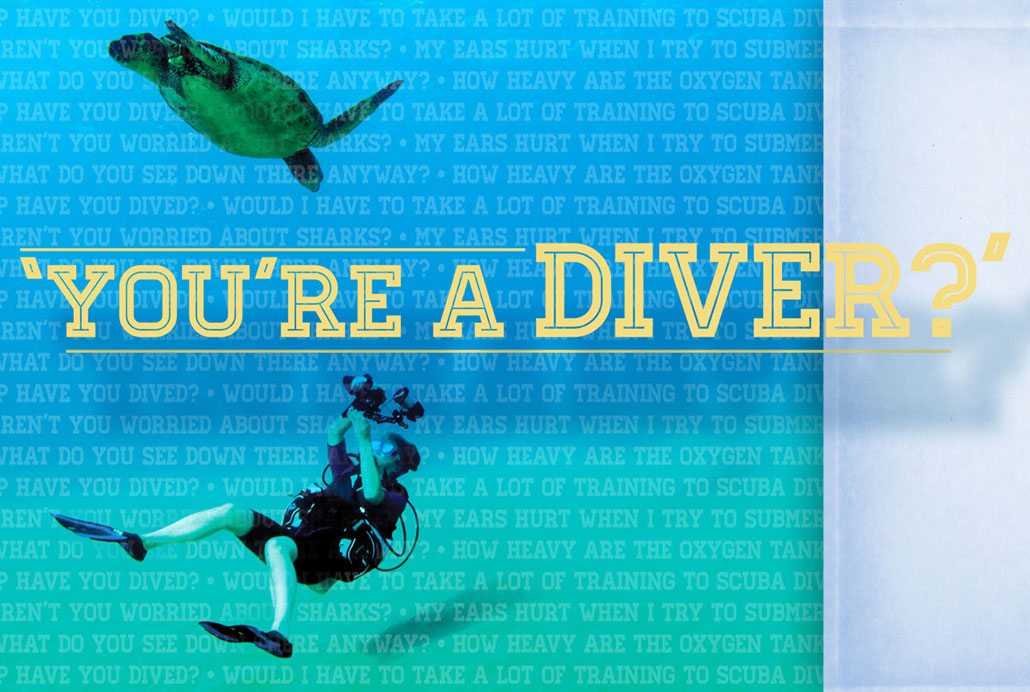

I’ve had virtually the same conversation countless times in the past 30 or so years. It usually goes something like this: I’m participating in some nondiving activity — enjoying social time with friends, meeting new people while participating in a sporting event, even waiting in a long line or during a flight to a dive destination. Small talk with the person beside me leads to discussion of how else we occupy our time other than whatever we happen to be doing (or waiting to do) at that moment.

I mention that I write for a scuba magazine and the usual response indicates surprise, followed by the question, “Do you dive?” Once I explain that, yes, I do dive; in fact I taught scuba for many years, the next response is often a mixture of curiosity, disbelief and fear. The inevitable misconceptions come out first, followed by a veritable interrogation about all things diving related, to which I enthusiastically respond.

Defining Danger

It’s ironic. I have a nephew who is a professional skydiver. He thinks scuba is dangerous and I think he’s nuts for jumping out of a perfectly good airplane multiple times a day. I like to relate that fact to people because I believe the perception of danger for an activity is closely related to the amount of relevant knowledge and experience one has.

I once thought that diving sounded like an extreme sport. And way back when, scuba was considered the domain of macho males. But since that time equipment comfort, reliability and ease of use have made it practical for most people, even kids as young as 8, to enjoy scuba in safety and comfort.

And training programs are no longer reminiscent of military boot camp. I explain that the academics are taught in small, personalized groups at local dive centers and can even be presented online at the student’s convenience. And modern hands-on teaching methods have opened the door to the underwater world for just about anyone who wants to dive, regardless of age and physical ability, although a medical clearance may be required. Scuba has even proven to be a life-changing activity, with programs like Dive Heart and Wounded Warriors, for those with disabilities.

It’s obvious during these conversations with nondivers that I’m no macho daredevil, yet once I discovered how much fun scuba is and how easy it is to learn, I was instantly hooked.

Aren’t You Worried About Sharks?

Even though I’ve assured my listeners that scuba is actually quite safe given the right training and attitude, there is still the matter of dangerous underwater creatures. In the minds of nondivers, sharks are often number one on that list — and perhaps make up the rest of the top 10 as well.

The reality is that humans are much more dangerous for sharks than sharks are for us. Millions are slaughtered every year for food, exotic remedies and sport. Or killed as bycatch in commercial fishing. When the number of these apex predators is severely diminished the balance of that ecosystem is disrupted and the damage snowballs.

“But don’t sharks attack divers?” they ask. Actually, many of the 375 species of sharks, which range from the 8-inch (20 cm) pygmy to the 40-foot (12 m) whale shark, are bottom or plankton feeders; only a few species have been known to harm humans, most notably tigers and great whites. The reef sharks and other small species that divers are most likely to encounter are perfectly harmless as long as they are treated with the respect that all aquatic creatures deserve.

Attacks on humans by sharks are very rare, although such events seem to trigger media attention when they do occur. Scuba divers are at even less risk than swimmers or surfers because most shark attacks occur when the shark mistakes the person on the surface for a seal or other natural food source.

I like to add that some of my best dives ever have been watching schools of scalloped hammerheads off Cocos Island, Costa Rica, or participating in shark feedings in the Bahamas and Tahiti. Cage diving to see great whites, tigers, bulls and other large sharks has become popular in South Africa and California. If this doesn’t diminish the shark anxiety, I remind nondivers that there are lots of interesting freshwater dive sites with no sharks.

My Ears Hurt When I Try to Submerge

Just about anyone who has been swimming or snorkeling in clear water deeper than he or she can stand up in has tried to dive down toward the bottom. But for many the breath-hold dive ended abruptly when they experienced a sudden, sharp pain in their ears that subsided as soon as they reversed course and headed for the surface.

I assure my nondiving acquaintances that it doesn’t necessarily mean that you are unable to dive just because of ear pain. In most cases it simply means that you are using the wrong technique to equalize the pressure inside and outside your ears.

Equalizing is necessary as you descend in water, even as shallow as six feet (2 m) or so, because water is much denser than air (about 800 times). The water exerts more pressure on the outside of the eardrum than the air in the middle ear exerts on the inside. If the pressure is not equalized the eardrum presses inward, causing pain — a stronger version of the discomfort that occasionally happens when descending in an airplane.

At this point in the conversation I often ask my nondiving friend to pinch his nostrils shut, close his mouth and attempt to blow out gently through the nose, a technique known as the Valsalva maneuver. Unless he has a lot of upper respiratory congestion, a subtle popping noise occurs. What is happening is that the eustachian tubes, which run from the back of the throat to behind each eardrum and serve the purpose of equalizing pressure when necessary, are being forced open by applying positive pressure from the lungs.

Even if you have tried the Valsalva maneuver when breath-hold diving down headfirst, it may not be effective because you are attempting to push air downward into your head, which is opposite the natural flow. Equalizing is much easier to accomplish when descending feet first; therefore that is the method taught to scuba divers.

The vast majority of people can equalize all their air spaces when descending on scuba, just by applying the correct technique.

I Could Never Dive, I’m Claustrophobic

When told this, I say first that underwater does not feel like a confined space. The experience of floating weightless, the ability to do somersaults or to hover motionless in any position is actually quite freeing.

In tropical oceans as well as under the ice, the visibility can reach 100 feet (30 m) or more. Even in freshwater venues, in which visibility is typically less, many divers enjoy the freedom from gravity as much as they do the underwater sights. Scuba diving has often been likened to flying underwater.

I’ve led many hundreds of vacationers on introductory dives, a program that allows nondivers to try scuba under the direct supervision of a dive instructor. Those who expressed concern about feeling claustrophobic underwater on scuba typically did not.

Unfamiliarity with scuba equipment can make breathing underwater feel a bit awkward at first, but the scuba mask covers the nose as well as the eyes, providing a clear view of your surroundings while preventing water from entering the nose. You breathe through the regulator second stage, which has a mouthpiece much like a snorkel. It may require a simple mental adjustment to comfortably inhale and exhale through the mouth, not the nose, but with a little practice breathing correctly and continuously on scuba becomes normal.

What Do You See Down There Anyway?

After we’ve discussed the fears and misconceptions that nondivers tend to have regarding scuba diving, doubt commonly turns to curiosity. Those who have not spent time peering beneath the surface wonder what holds a diver’s interest underwater. That’s not hard to explain.

The range of sights and experiences available to scuba divers is as varied as the bodies of water in which they submerge. Quarries, lakes, rivers, caves, hot springs, oceans and seas — from ice cap to ice cap and everything in between, a whole new world awaits.

In the course of a conversation about scuba, the question almost always arises: What is my favorite place to dive? I do admit that I personally prefer warm water, which includes a huge variety of destinations and attractions. Others revel in the excitement of venturing under the ice, exploring a shipwreck or cave system, riding a river current or searching out the “big stuff” wherever they roam. Still others just appreciate blowing bubbles at a dive site close to home.

One thing that is true wherever scuba is enjoyed is that the life-forms encountered underwater are very different from land creatures. Aquatic plants are generally easy to recognize as such because they are green like their above-water counterparts. But then you discover kelp the size of trees, with a holdfast instead of roots and no massive trunk.

And consider soft corals, anemones and even feather duster worms, to name just a few creatures that look like plants but are really sedentary animals. Hard corals mimic rocks until the polyps extend their tentacles to feed. Urchins, the pin cushions of the sea, seek protection during the daytime and walk along the bottom at night feeding on algae.

Even recognizable animals feature unique body shapes and camouflage colorations designed to help find and capture food and avoid becoming food. Fishes blend into their surroundings or are painted in Picasso arrangements of pattern and color to fool both predator and prey. Crustaceans range from spine-covered Maine lobsters, to translucent freshwater crayfish, to hermit crabs in borrowed shells, to brightly adorned cleaner shrimp. Shape- and color-shifting octopuses are some of the most fascinating marine creatures.

But living things aren’t the only attractions that lure divers. Historic shipwrecks hold a fascination for many. World War II wrecks abound off the eastern coast of the United States, as well as several destinations in the western Pacific. The Great Lakes are the resting place of centuries of commercial vessels that sank during fierce storms. Plus, coastal areas such as British Columbia, Southern California and Florida have been steadily creating artificial reefs from mothballed military vessels.

In a lifetime one could never experience all there is to see and do underwater, but it sure is fun to try.

How Deep Have You Dived?

Personally, I tell nondivers that I have dived to 130 feet (39 m), which is the recreational diving limit. But only if there is something specific to see down there, such as a shipwreck. There is a lot more life at shallower depths. The more light, the more life.

No one wants a science lesson during a casual conversation, but it is easy to explain what happens to light underwater by relating it to the colors of a rainbow. Just as light is bent as it travels through droplets of water vapor in the atmosphere, splitting it into a band of colors ranging from red to violet, light is similarly bent as it enters the surface of a body of water.

The red light waves are the longest, carrying the least energy, and therefore are absorbed first by the water molecules. The blues and violets are the shortest waves and are the last to disappear. For this reason you don’t have to dive very deep before everything takes on a blue cast. The shallower you dive, the more light and the more color; i.e., everything is prettier.

If my listener seems interested, I discuss another very important reason for diving only as deep as is required to see the underwater attractions of a site. Because water is much denser than air, the ambient (surrounding) pressure on the body’s air spaces increases quite rapidly as you descend. It doubles in the first 33 feet (10 m) of depth in salt water. The consequences of this are that you consume the compressed air in your scuba cylinder faster and also absorb more nitrogen into your system. Therefore, the deeper you go, the shorter your allowable bottom time (the number of minutes you can spend at depth without mandatory decompression stops).

Most people have heard of the bends, which, I’ll admit, sounds mysterious and sort of scary. This condition, actually termed decompression sickness, can occur when a diver absorbs more nitrogen into his tissues than can safely be offgassed (eliminated through normal breathing). As he ascends and the pressure decreases, excess nitrogen can bubble out of solution in the tissues into the body’s air spaces, causing pain and tissue damage. This type of injury may require a trip to a recompression chamber.

For recreational divers, going deep is not the goal. Maximizing bottom time is more important. Technical divers are able to dive to greater depths safely by completing extended-range training and using specialized equipment configurations, but even then few divers go deep just to say they went deep.

How Heavy are the Oxygen Tanks?

First, I explain that recreational divers do not breathe pure oxygen. In fact, breathing pure oxygen underwater could be fatal. In most cases our scuba cylinders contain plain-old air that is made up of only about 21 percent oxygen; the rest is mostly nitrogen. The only difference between the air we breathe on land and that inside a recreational scuba diver’s tank is the density. Breathing gas is compressed from 14.7 psi (pounds per square inch — 1 bar), the standard weight of the atmosphere at sea level, to from 2,500 to 4,000 psi (172 to 276 bar). By compressing gas molecules into the tank divers gain significantly more breathing gas in a relatively small container.

Stuffing so many more molecules into a fixed-size scuba tank does increase its weight. Depending on its size (e.g., 50, 72, 80, 110 cubic feet) and composition (i.e., steel or aluminum), scuba cylinders vary greatly in weight. An assembled scuba unit, consisting of a buoyancy compensator (BC) and regulator with gauge console and two second stages, mounted on a single cylinder can weigh up to 40 pounds (18 kg).

The good news is that once underwater, the scuba unit weighs nothing. Especially when wearing exposure protection such as a wet suit or dry suit, divers typically need to carry lead weights to create negative buoyancy so they can descend.

Some recreational divers use a different gas mixture, called nitrox (32 to 36 percent O2), that provides advantages over air in avoiding decompression sickness or extending bottom time. Nitrox, however, requires specialty training and strict adherence to depth limitations.

Regardless of the type of gas you’re breathing, once you reach diving depth and add air to the BC to produce neutral buoyancy (neither floating up nor sinking), you’ll experience that wonderful feeling of weightlessness.

Would I Have to Take a Lot of Training to Scuba Dive?

A great question. It tells me that the conversation has sparked some interest in diving beyond mere curiosity. I’ve already mentioned introductions to scuba for nondivers. These short programs start with an hour or so of basic safety and equipment use information. This is followed by donning scuba gear and practicing simple exercises in a confined-water (i.e., pool-like) setting with a scuba professional.

An introductory experience may proceed to a closely supervised open-water dive. This adventure takes less than a full day and is very popular at warm-water dive destinations. Participants don’t receive a certification, but may be permitted to repeat the open-water dive portion within a specified period without redoing the academics and confined water.

The next step in becoming a scuba diver is to enroll in an Open Water or Scuba Diver certification course. Earning a certification card allows holders to purchase air fills and book space on a dive charter boat.

Once a prospective student has made contact with a scuba training center, he has a number of choices. Academics can be completed online or in a traditional classroom setting. Confined-water skill sessions, during which students learn and practice how to use scuba equipment safely, can be accomplished in a few intense days or spread over several weeks. Students demonstrate mastery of these water skills during four open-water training dives scheduled over two or more days.

Newly certified divers are considered qualified to dive independently with a buddy in conditions like those in which they were certified. The best way to expand your scuba skills and experience is to enroll in additional scuba courses. Overview courses provide a brief introduction to common diving activities, such as deep diving, night diving, navigation and perhaps underwater imaging or drift diving.

Specialty courses delve deeper into specific diving activities. Planning and specialized equipment are covered as well as skills specific to the activity; most specialty certifications require one or more related dives. Diver Rescue is recommended for every diver; plus, there is a specialty course for just about every scuba-related activity you can imagine.

To further expand their scuba skills, divers who complete a prescribed number of dives and specialties receive recognition certificates. Some branch into scuba leadership training with divemaster and instructor courses and internships. Scuba training can be as basic or as comprehensive as you desire.

Continuing the Conversation

I never tire of explaining a little bit (or a lot) about my scuba passion to anyone who shows interest. Hopefully, with understanding will come an urge to try it themselves, or at least to not consider me a strange, underwater daredevil.

The neat thing is that it doesn’t require the knowledge of a scuba instructor to dispel common fears and teach nondivers how enjoyable — and safe — scuba diving really is. Anyone with an Open Water scuba certification can answer most questions that nondivers pose. So the next time you encounter someone who asks, “Do you dive?” proudly tell them, “Yes, I am a certified diver,” and let the conversation begin.