You’re gliding into a vast underwater cavern. In the crystal-clear water all around you majestic stalactites hang down from the cavern ceiling like icicles. Cone-shaped stalagmites rise up to meet them. Gnarled tree roots snake through the cavern’s roof to get a drink of water. But wait…you must be dreaming, because you’re only an Open Water-certified diver. You can’t possibly be exploring the inner sanctum of an underwater cavern, because this type of diving is suited for only those expert divers who’ve had a lot of advanced training, right?

Well, yes. And no.

While cavern exploration shouldn’t be attempted without proper training, there are places where divers can enjoy the cavern diving experience without specialized training. In some areas cavern interiors have been made safe for novice divers. In other areas, professionally trained guides lead divers through caverns on introductory tours. These advances have opened the world of cavern diving to divers of various experience levels. Many who complete the cavern diving experience go on to acquire the training necessary to become full-fledged cavern explorers.

Caverns and Caves Defined

What’s the difference between cavern diving and diving in a lake, quarry or ocean? Caverns and caves, like shipwrecks, are called overhead environments, because a physical barrier exists between the diver and the surface. This barrier prevents a diver’s direct ascent to the surface and is one of the main reasons why cavern divers must receive training beyond that which is offered in Open Water class.

What’s the difference between a cavern and a cave? The National Speleological Society’s Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS) defines a cavern as the opening area of a cave that receives direct sunlight, goes no deeper than 70 feet (21 m) and is within 130 linear feet (39 m) of the cave entrance. Basically, if you don’t see natural light, you’re in a cave. And since a cavern is defined by natural light — sunlight, caverns do not exist at night. Cavern diving is strictly a daytime endeavor.

There are four different types of caves: littoral (sea), coral, solution and lava tubes.

Sea caves are usually formed by wave action and are not extensive. They are generally chamberlike in shape and can be found in coastal areas, including the Great Lakes, New England, the Sea of Cortez and California.

Coral caves are formed when corals grow together to form arches that create tunnels and passageways. They’re often draped with colorful marine life and may provide a home to fishes like copper sweepers or a sleeping nurse shark.

Lava tubes are formed by volcanic action; as lava flows from a volcano into the sea, the surface of the flow cools and hardens while the molten inner core keeps flowing, eventually creating a hollow tube. Lava tubes are most common in Hawaii and the Northwest Pacific coast.

Solution caves are formed over eons of time by water containing carbonic acid percolating through limestone and dissolving the rock. As the rock dissolves, the cave is formed. Solution caves are a source of fascination for geologists and cavern/cave explorers alike. Divable caverns can be found in Florida, Missouri, Texas, the Yucatan Peninsula and throughout the entire Caribbean region.

The Cavern Diving Experience

Just like any type of dive site, cavern diving amenities and conditions will vary from one location to another. Many areas feature on-site dive centers that offer everything from air fills and equipment to guided tours and complete certification courses.

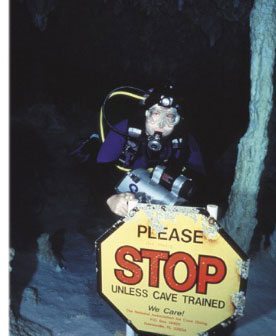

Divers who visit Florida’s springs enter the water at sites where Spanish moss hangs from magnificent cypress trees. The water is cool and crystal-clear, and suspended platforms are often in place to keep divers from kicking up silt from the bottom. At the mouth of the cavern, an out-flowing current can usually be felt, as the underground river forces its way through the small opening. A large, permanent guide line anchored to the cavern floor marks the exit. Catfish and freshwater eels scurry to escape the glare of divers’ lights. Farther inside, where daylight ends and the cavern walls grow narrower, a sign indicates the transition into a “cave divers only” area — a labyrinth of tunnels that should be entered only by those with full cave certification and proper equipment.

Another popular destination for recreational divers to experience cavern settings is along Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula in an area known as the Riviera Maya, which extends from Playa del Carmen south to Tulum. Cenotes (see-NO-tays), natural sinkholes, are the entrances into numerous underground solution cave systems.

After a ride through the steamy jungle, divers reach the cenote, which at first glance doesn’t look too appealing — a hole in the ground with a set of stairs that leads to the water below. Trained guides escort divers on a tour that is part geological wonder, part mythical adventure. Besides the numerous sunny openings to the cenote, small holes in the jungle floor/cenote roof allow shards of light to penetrate the water like laser beams. Divers weave in and out of gigantic columns formed by the mating of stalactite and stalagmite. Smaller stalactites the size of soda straws cover the ceilings.

The number of divers visiting the cenotes has been doubling each year, according to Scott Carnahan, who operates a dive center in Playa del Carmen. “It’s the biggest growth area in diving that I have seen in the past 10 years,” he says. He estimates that about 90 percent of the Riviera Maya’s diving customers were first-time cenote divers who participated in cavern tours with professional guides.

Novice divers who engage in recreational cavern diving, whether on their own at specially prepared sites or on guided tours, should not confuse “sport” cavern diving with technical cavern and cave exploration.

The Cavern Diver Course

The Cavern Diver Course

Many divers who enter a cavern on a guided tour exit mesmerized, eager to learn more about the cavern environment and how to safely explore it on their own. Enrolling in a Cavern Diving specialty course is the next step. Several scuba training agencies offer cavern diving courses. Most agencies have developed programs based on the course standards of the National Speleological Society, founded in 1941. The NSS Cave Diving Section developed the first cave diver training program in the 1950s. Another leading cavern and cave diving organization, the National Association for Cave Diving, was founded in 1968 with the goal of providing safe cave diving through training and education.

Prerequisites for cavern specialty courses vary depending on the training agency, but most include a minimum age of 18, Open Water or Advanced Open Water scuba certification and at least 20 logged dives.

Most cavern diving courses can be conducted in a weekend and usually consist of at least six to eight hours of academic lessons and field exercises, and three or four dives over a two-day period.

When you enroll in a cavern diving course, in addition to learning the basics of cavern geology, you’ll be taught the proper planning, procedures and techniques for — and hazards of — diving in overhead environments within the limits of light penetration.

Equipping for Cavern Diving

Standard scuba gear is reconfigured to reduce the risk of entanglement or stirring up silt that will reduce visibility. Dangling gauge consoles, inflator hoses and octopus regulators are shored up. Snorkels are removed since they prove useless in an overhead environment and present an entanglement risk. Flapping fin straps are taped down and accessory gear is stowed or secured with loops of surgical tubing or other fasteners.

One of the most important equipment items used by cavern divers is the reel, which is used to lay down a guide line from the cavern entrance. The guide line marks the entry/exit point and may be the diver’s only means of finding the way out if visibility becomes reduced. Divers who enter caverns without a guide line risk becoming lost and drowning.

Even though cavern divers are taught to remain within the area of natural light, each diver is equipped with one primary dive light and at least one backup light.

Because water temperatures in most caverns average in the mid-60s to mid-70s Fahrenheit (low-30s to low-40s Celsius) a wet suit is recommended, even in tropical locations like Florida and Mexico. Gloves are not recommended, as they may reduce a diver’s sense of touch, which is important when using a guide line in limited visibility.

Additional cavern diving accessories include a knife or line-cutting device and an underwater slate.

Skills and Drills

Skills and Drills

Participants start out performing a series of land drills that teach basic reel and guide line use. Training then moves to a shallow open-water site, with more emphasis on laying and following a guide line, and a host of other skills, including emergency procedures such as out-of-air situations and responding to a silt-out. Problem solving and confidence building are emphasized.

Communications skills are sharpened. In addition to hand and light signals, and message writing on slates, cavern divers learn “touch” signals that allow them to communicate in zero-visibility conditions.

Buoyancy control and underwater propulsion skills are introduced, with variations from the way these skills are usually presented in Open Water class. Cavern divers are taught to position their weights slightly forward of the waist area for better horizontal trim. Neutral buoyancy is practiced to perfection. Long, fluid fin kicks with almost no bend at the knee give way to the bent-kneed “cave diver’s kick” that helps minimize silting when moving through caverns.

Cavern divers don’t operate merely as buddies, but as teammates. Participants in a cavern diving course learn to operate as a unit and be able to assist each other in an emergency. When entering a cavern, the leader lays down a guide line and others follow; each maintains contact with the guide line by making an “OK” sign loop around it with a thumb and forefinger.

Air supply management is another important skill, because a direct ascent to the surface isn’t possible in the event of an out-of-air emergency. This is where the “rule of thirds” comes in. A diver uses one third of his or her air supply to enter a cavern, and one third to exit. One third remains in reserve in an emergency.

Team members are taught to routinely monitor and communicate their air supplies. The first diver in a team to reach one third of his air supply signals that it’s time to turn around and begin exiting the cavern.

All training dives are conducted under the supervision of a qualified cavern diving instructor.

Accident Analysis

Cavern diving is not without risk, and has claimed the lives of many divers over the years. Accidents involving fatalities are carefully analyzed to determine the direct and indirect causes. Virtually every cavern and/or cave fatality has been linked to one or more of the following factors:

- Failure to run a continuous guide line to open water.

- Failure to adhere to the “rule of thirds.”

- Lack of proper training or exceeding the limits of training.

- Inadequate number of lights.

Despite its inherent risks, cavern diving is clearly gaining in popularity in both the recreational and technical diving communities. It’s also clear that the risks can be mitigated with proper training and equipment. Even if you don’t plan to become a frequent cavern or cave explorer, the skills and drills taught in a cavern diving specialty course can help you become a better diver.

Cavern Diving

For more information on cavern diving, contact one of the following agencies:

- International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD), www.iantd.com, (305) 751-4873

- National Association of Cave Diving (NACD), www.safecavediving.com, (888) 565-6223

- National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), www.naui.org, (800) 553-6284

- National Speleological Society’s Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS), www.nsscds.com, (570) 223-1732

- Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), www.padi.com, (800) 729-7234

- Scuba Schools International (SSI), www.ssiusa.com, (800) 892-2702

- Technical Diving International (TDI), www.tdisdi.com, (207) 729-4201

Recommended Reading

“The Cenotes of the Riviera Maya” by Steve Gerrard

“NSS Cavern Diving Manual” by Zumrick, Prosser & Grey

“Cave Diving Communications” by Joe Prosser & H.V. Grey

“The Cave Divers” by Robert Burgess

By David Prichard And Cathryn Castle

Photos By Lily Mak