Finding a direction in life is not always an easy thing to accomplish, especially for those with many interests, many desires and many directions to travel. Finding the right career often means matching your skills and abilities with the right opportunities, but it might also be a matter of following your passion. And whether you’re just starting out or looking for a change of direction, you might romanticize about the various options that life might present, perhaps a life of excitement and adventure.

Just the sound of some careers conjures up a romantic image of a steely-eyed adventurer: a stunt double daring to make the impossible look simple, a smoke jumper parachuting into a hair-raising wilderness blaze to save lives or an astronaut rocketing into the unknown inside a high-tech capsule. But for those of us with an underwater bent, there’s another job might that ignite our passion: the aquatic tough-guy action hero we call a commercial diver. As it turns out, that commercial diver might just be a little bit of each: making the impossible possible; descending into a hair-raising wilderness or exploring the unknown while living in a high-tech steel chamber. And while it might sound romantic to play the role of the tough action hero, it’s also a tough job.

Getting it Done

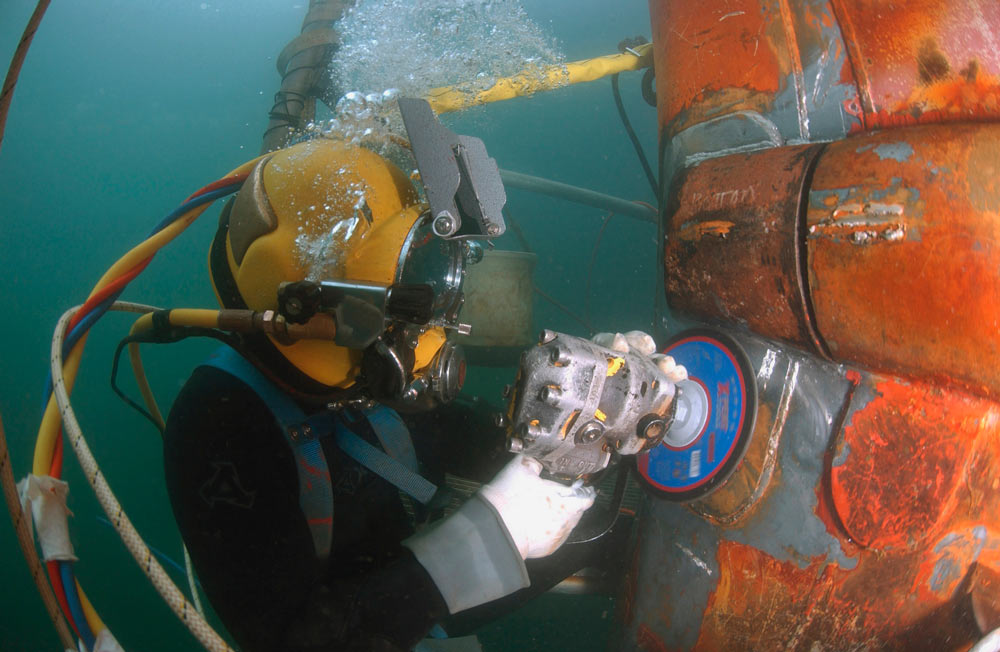

When we think about commercial divers, we might picture a hardhat diver on an offshore oil rig, hundreds of feet below the waves, welding together steel structure and pipes. In reality, the job of a commercial diver is much more diverse — the underwater Swiss Army Knife of the construction industry performing a number of services in a broad spectrum of environments. Commercial divers are called on to perform a variety of tasks using an array of tools to construct, inspect and repair virtually anything that exists in a submerged environment. But as Brian Staley of The Ocean Corporation describes it, “A commercial diver is a construction worker that goes underwater to do his job.” Or as Allen Garber of CDA Technical Institute in Jacksonville, Florida puts it, a commercial diver must be “a jack of all trades.” It certainly isn’t for those who don’t want to get their hands dirty or do an honest day’s work. It is for those who want a meaningful job and commensurate compensation.

Mike Rowe, best known for his Dirty Jobs series on Discovery Channel that explores blue-collar careers, was recently a keynote speaker for the annual Human Resources Technology Conference and Exposition in Las Vegas, where he spoke about the powerful sense of satisfaction that comes from doing an important job. “We all want to end up engaged doing meaningful work, passionate about what we do,” notes Rowe. “It’s just a question of what route you want to take.” To a great extent, Rowe is right. And one route to consider exploring will take you straight out to sea. John Paul Johnston, Executive Director of Divers Institute of Technology in Seattle says one of the primary reasons people choose commercial diving as a career is the adventure. He explains, “Our divers tend to be adventurous types who enjoy the camaraderie — it’s a small industry — and they tend to like the challenges associated with working underwater.”

The Driving Forces of Opportunity in Commercial Diving

More than a decade ago, Hurricane Katrina (2005) ripped across the Gulf of Mexico, leaving a trail of wrecked oil rigs in its wake. Half the oil rigs in the Gulf were literally swept away and half of those remaining needed extensive repairs. That created a massive demand for commercial divers. But even though Katrina is well behind us, the demand for commercial divers remains strong.

According to the experts, several factors appear to be driving the current boom in commercial diving. First is a renewed push to develop gas and oil in the United States. “We’re seeing an increase in offshore oil projects,” says Todd Matthies of Minnesota Commercial Diver Training Center, “which means a lot of new jobs are opening up. Commercial divers are in high demand. Now is a great time to enter the industry.”

Another factor is an uptick in the number of storms and hurricanes. Any time a storm passes within a prescribed distance of oil rigs or conditions exceed a specified level, inspections are required on the oil rigs, with follow-up repairs and replacement performed before production activities can restart. Likewise, flooding from storms can result in structural damage to bridges, dams and other submerged structures. Johnston reminds us, “In the northeast, repairs from the devastation caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 are ongoing. And we’ve had several major storms hit U.S. coastal regions since then.”

A third factor is delayed maintenance and the resulting poor condition of infrastructure around the country. Decades of wear, tear and neglect have left much of our inland infrastructure in deplorable condition. Commercial divers are needed to support maintenance of nuclear power plants, municipal wastewater facilities, dams, ports, harbors and water towers. As state and federal agencies work to restore that infrastructure, the demand for commercial divers remains at a high tempo. High on the to-do list for many states are bridge inspections, which are typically required every two years, and this requires the services of commercial divers. “It’s not just big bridges like the Golden Gate,” explains Staley, “but even small bridges over rivers and bayous.” Right now, many states and municipalities are behind in their required inspections — which again means a big demand for divers.

Combined, these three factors conspire to create the strongest market for commercial diving since Katrina. Johnston adds, “Our graduates aren’t limited to North America. We’re regularly placing divers in the international sector, especially veterans who have experience living and working overseas.” All this means a world of opportunity for those with the desire and training to take advantage of it.

The Bottom Dollar in Commercial Diving Careers

Clearly, earning a good living is important to just about everyone and a career in commercial diving answers the mail in this department. Typical pay for an entry-level commercial diver is in the range of $1,600 to $1,900 per week, with most divers working from 30 to 35 weeks per year. That translates to a $60,000 a year starting pay. And with experience and advanced qualifications come bigger paychecks, with saturation divers easily bringing in $1,000 or more per day.

The flip side of the coin is long days and the need to travel. As Garber points out, being away from home for extended periods can be the toughest part of the job. There are no weekends, no holidays and workdays can be 10 to 12 hours long.

Right now, it is estimated that roughly 2,000 commercial divers work in the United States, with about 200 new divers entering the field each year. And that still isn’t enough to meet the demand that spans a broad spectrum of environments. Depending on an individual’s interest, there can be opportunity around just about every corner.

As Geoff Thielst of Santa Barbara City College explains, “Roughly half of our graduates go to work in the oil fields, with another 25 percent pursuing scientific diving, public safety diving, remotely operated vehicles (ROV) operations, harbor patrol and other scientific careers. Still others go on to earn a four-year degree in engineering or pursue other career options.”

Meeting the Demand as a Commercial Diver

The requirements for becoming a commercial diver are not at the outset particularly exclusive. Several basic criteria must be met to pursue training as a commercial diver. First, most schools require a minimum age of 18 years with a high school diploma or GED as a minimum educational requirement. Some schools also require prospective students to pass the Wonderlic aptitude test, which measures problem solving along with basic math and reading comprehension.

Next is some basic mechanical aptitude: those who like to tinker and repair are more likely to succeed as commercial divers. The third criterion is a moderate swimming ability. You don’t have to be a competitive swimmer, but comfort in the water is very important. On the other hand, claustrophobia and commercial diving just don’t mix well, so that’s another critical criterion. And finally, a person must pass a diving medical exam. Clearly a commercial diver must be in good health and free of any contraindications.

Beyond the basic education and physical requirements are the personal characteristics that make an individual more likely to succeed in a physically, and sometimes mentally, demanding career. There is a certain mental toughness and spirit required to face the challenges of the deep and those aren’t easily measured. As Garber suggests, three factors are important for success: dedication, drive and commitment.

Staley agrees, noting that one characteristic that makes a successful commercial diver is having a stubborn streak. As he explains, a successful commercial diver is one who sticks with a job, even through adversity, to get the job done.

Among those who typically succeed in commercial diving are former military. These people are accustomed to being deployed and following a chain of command — and their families are used to the demands and able to cope and support. Johnston is proud to comment that Divers Institute is veteran-owned and over 50 percent of its staff (and currently 56 percent of its commercial diving program members) is former military. “We are proud to provide a veteran-friendly learning environment,” he explains. Others who adapt well to the rigors of commercial diving are farm kids and those with a background in industrial trades. Surprisingly, one additional qualification sought by some employers is a commercial driver’s license (CDL). “A lot of times,” notes Staley, “a job might only be one day and having a CDL allows the diver to help get the equipment to the job site.”

Commercial diving is a physically demanding job and it takes a person who is physically fit. Beyond age 45, divers are typically restricted from deep diving due to physiological concerns, so most companies like to see individuals entering the field no later than their mid-30s. Still, older individuals have been known to complete training and many continue working as active divers into their 50s. While women are under-represented in commercial diving, the latest trends have seen as high as 10 percent women entering training for commercial diving.

A Course for Adventure

You might think that as a certified diver, or especially as a certified scuba instructor, you would have an edge getting into or completing commercial diver training. And while scuba experience can be a boost — or a requirement for some programs — it isn’t always as big a boost as you might think.

Perhaps, just as important as basic scuba skills is being a hands-on person who is quick with the turn of a wrench. The job of a commercial diver often requires a sharp eye for inspections but more often the diver becomes an extension of his or her underwater tool kit, performing any number of hands-on tasks needed for inspection, construction or repair.

To say that the training for commercial divers is tough is an understatement. It is not only physically demanding but it requires a boatload of basic and advanced diving topics. Commercial diver training focuses sharply on decompression theory, mixed breathing gas operations, chamber operations and dives deeply into physiology, physics and diving medicine. Beyond the book work is the hands-on element of training where students learn to use the dive gear, tools and support equipment.

Without a doubt, part of the hands-on training takes place in the confined waters of a pool, but most also get their divers into open water environments. And these environments bear little resemblance to the Caribbean reefs we may have come to enjoy. Common to commercial diving are conditions of frigid waters, powerful currents and zero visibility, not to mention penetration deep into overhead environments. Commercial diver training is geared toward these conditions, as well as diving in waters polluted with chemical and biological waste or other hazardous materials. Matthies points out that training in Minnesota prepares students for all the realities of the job. “We have a training tank inside the school where students will first learn the proper use of equipment, but most of the dive training is done in the Cuyuna Mine Pits and in the Mississippi River. Our graduates leave here with the skills they need to do the job.”

That said, the equipment used in commercial diving might include the typical scuba gear with which we’re familiar, but more commonly involves surface supplied diving equipment including breathing gas and communications cable, heated water supply, a dry suit and a full-face mask or helmet.

Where recreational diving focuses on no-stop diving (no decompression required) and a 130-foot (40 m) depth limit, commercial diving can involve diving to depths of 1,000 feet (305 m) or more, with exotic mixes of breathing gas, special equipment and a pressurized chamber for decompression. Such deep diving relies on saturation diving techniques, where divers are maintained at pressure for long periods of time so that no further decompression obligation is incurred. As such, the divers remain in a pressurized chamber or habitat during off hours. If you compare recreational diving to flight in a small plane, commercial diving is the equivalent of a space mission.

The culmination of the training is the coveted certification that serves as the credentials to land a job: entry-level certification from the Association of Diving Contractors International (ADCI).

Making the Grade

No matter where a commercial diver is employed, it is anything but a 9 to 5 job. It often involves long days and long periods of travel from home. Those who find work in the offshore oil industry can expect to spend two to six weeks at a time at sea. While we might imagine working offshore in the Gulf of Mexico, many divers find work in other offshore regions including the United Kingdom’s North Sea and off the coasts of South America and Africa. Johnston cautions, “You’ll always need to go where the work is, so travel is just a part of the job. You’ve got to be mobile.”

A typical day for a diver on an oil platform starts at 6:00 am with a safety briefing. Typically, a diver begins in the stand-by diver position, waiting and ready if the situation demands and helping out as needed. Next comes the actual dive, which may be long and exhausting. Once the work is completed, a diver spends the requisite hours decompressing in a chamber. Once the decompression is complete, the day is done.

For inland operations, there is less routine and little down time. The actual diving may be short, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. As Staley explains, “A lot of what a commercial diver does is logistics: getting the equipment on site, set up, assembled, inspected, tested and repaired. In a 12-hour day, the actual diving might only be an hour.”

Despite the high demand, there’s no “easy bucks” in the commercial diver business. Divers earn every penny they’re paid. But as Garber points out, “It takes two to three years to become established in the industry and to build a reputation. Most start out as a tender, working deck support jobs and eventually move up to the position of diver.”

A commercial diving operation requires significant support roles that trained divers fill. These include rigging or setting up equipment, rack box operations, crane operations support, operating a decompression chamber and tending divers. In fact, many trained divers may work those support roles for up to a year or more before taking on the role of diver themselves.

As divers gain experience, build reputations and earn qualifications, their earning potential increases as well. For example, divers can earn incentives for diving at greater depths with premiums for saturation diving. But that takes time, hard work and dedication.

As Staley points out, “A major demand in commercial diving is nondestructive testing (NDT), which is used extensively both above the water and below. So even if an individual trains as a diver and decides later on to leave the underwater scene, that NDT certification is a valuable ticket to a good-paying job.”

Where Your Compass Points

If you’ve ever considered a career in commercial diving, it might be time to act. “This is an excellent time to get into the business,” stresses Garber. “There is a very strong demand and more companies are looking to fill positions. In fact, for the past nine months we’ve been seeing recruiters come looking for qualified graduates from our program.”

Not everyone is cut out for commercial diving but if your career compass points to undersea adventure, that action hero role as a commercial diver might just be a good direction to head.