HERE’S A CHALLENGE FOR YOU: Without using art of any kind, describe nudibranchs and flatworms in a way that provides someone that has never seen or heard of these marine marvels with an accurate understanding of them. Whether you’re an old salt or a new diver, this is a tough task.

I am going to cheat on this one. Along with information that provides an overview of the natural histories of nudibranchs and flatworms, I am going to use some photographs to help you learn about, and distinguish between, nudibranchs and flatworms.

Nudibranchs and Their Kin

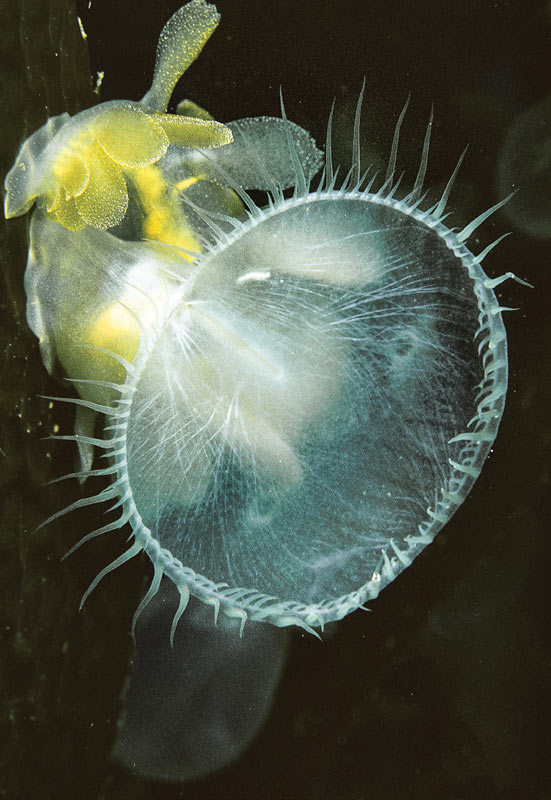

The lion’s mane nudibranch, pictured here, feeds using a greatly expandable oral hood bounded by fringed sensory tentacles. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Nudibranchs are described in the phylum Mollusca, a word derived from the Latin for “soft-bodied.” A partial list of other mollusks includes snails, scallops, oysters, mussels, squids, octopuses and cuttlefishes. Many of these animals are equipped with hard, external shells. But as is the case with squids, octopuses and cuttlefishes, nudibranchs exhibit an evolutionary trend toward the reduction, internalization or complete loss of the external shell that is present in many members of their phylum.

The word nudibranch is derived from the Greek for “nakedgills” in reference to their shell-less (naked) bodies and uncovered (naked) gills. Worldwide there are more than 3,000 nudibranch species with more being discovered on a regular basis. Collectively speaking, nudibranchs vary in size from small enough to fit on the fingernail of your little finger to just a few inches (1 inch = 2.54 cm) short of two feet (30 cm) long.

Further explanation of the taxonomic classification of nudibranchs can seem a bit like “science for science geeks.” But if you work your way through it, the explanation can help you avoid confusion and misidentification. So, here we go: Nudibranchs are further described within the class Gastropoda, a grouping that includes snails. Take the next taxonomic step and you will discover that all nudibranchs are members of the subclass Opisthobranchia. Other opisthobranchs include headshield slugs, bubble shells, sacoglossans and sea hares, creatures that are collectively referred to as sea slugs and that sometimes get confused with nudibranchs. So, while all nudibranchs are sea slugs — not all sea slugs are nudibranchs.

Go one more level on the taxonomic tree and you get to the order Nudibranchia. Within this order, nudibranchs are separated into the four suborders discussed below.

Dorid nudibranchs like this Spanish dancer have two sets of rhinophores located toward the front of the body. These are chemosensory organs. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

The Four Major Groups of Nudibranchs

There are four suborders of nudibranchs, groups commonly known as the dorids, aeolids (also known as eolids), dendronotids and arminids. The general body shape of the species in each suborder is significantly different than the body shapes of the members of the other suborders. The same is generally true with regard to their food preferences.

The suborder of dorid nudibranchs includes more species than the total of the other three suborders combined. The bodies of dorids are generally shaped like flattened ovals. Two sets of projecting structures extend from their bodies. The antennae-like structures toward the front of the body are called rhinophores while those near the back are the gills. Rhinophores are chemosensory organs that enable dorids to detect one another, prey and potential predators. In most species the gills are conspicuous, delicate looking, fluffy appendages that form a somewhat circular pattern around the anus.

Dorids known as cryptobranchs are able to retract their gills into a protective pocket on the top of their body, but other members of their suborder lack this ability and leave their gills extended at all times. It is the exposed gills of dorids that gave rise to the name nudibranch when these animals were first discovered.

Aeolid nudibranchs typically have elongated bodies that are equipped with two sets of sensory structures known as cephalic tentacles and rhinophores. These structures extend upward and outward from the front end of the body near the head. Both contain chemosensory receptors that enable aeolids to taste and smell various chemical cues in the water and substrate. The thin, cone-shaped extensions positioned in clusters along the back of the body are called cerata. They are branching extensions of the digestive organs and also serve in respiration. The skin of the cerata is often transparent, a characteristic that can make gut contents visible.

Dendronotid nudibranchs usually have a noticeably elongated body. The appendages on their gills take on a wide variety of shapes with the gills of many looking somewhat like tubes that are branched and tufted. While not as frequently encountered as dorids and aeolids, dendronotids such as the lion’s mane nudibranch, are quick to command our attention when they feed as they are equipped with a greatly expandable oral hood that is bounded by fringed sensory tentacles.

The suborder of arminid nudibranchs is filled with species that have a different shape than the species described in the other suborders.

Having a fundamental understanding of the taxonomy gives you an understanding of where nudibranchs fit into the animal kingdom, but it does very little to help those that are unfamiliar with nudibranchs understand why so many divers have fallen head over heels in love with them. This likely centers on the fact that nudibranchs appear in a stunning variety of colors, color combinations and bizarre-looking shapes. The cornucopia of colors is essentially a reflection of the myriad sponges, algae, cnidarians and other organisms that various nudibranchs feed upon.

The relatively flat bodies of flatworms distinguish them from nudibranchs and other marine worms. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Locomotion and Life Cycle

Nudibranchs move about in a variety of ways. They crawl by using wavelike motions that “flow” along the bottom of the foot, which is located on the underside of the body. In addition, some species can swim. Species such as the Spanish dancer, Hexabranchus sanquineus, appear to be quite graceful when they swim as they rhythmically undulate their body in a mesmerizing fashion. Swimming appears to be a more tortuous experience for many other species. Still other species sometimes hang almost motionless as they float in the water column or on the surface.

With many species living for only a few days to a few months after reaching sexual maturity, nudibranchs have relatively short life spans with many species living for one year or less. If they live a normal life, all adult nudibranchs eventually become hermaphrodites, meaning that each animal simultaneously possesses functional male and female reproductive organs. However, in some instances, described as protandry, the male organs develop in a given animal before the female organs, and in these cases these males mate with hermaphroditic adults. However, when nudibranchs mate it is often a case of boy meets girl meets boy meets girl as each partner fertilizes the other. Self-fertilization is not known.

The genital openings of all nudibranchs are positioned on the right side of the body. In many species very little, if any, courtship is involved. However, there are exceptions, especially among the aeolids. In many nudibranchs, copulation occurs in the virtual blink of an eye. But in a variety of dorids and some other species, the pair is engaged for significantly longer periods of time.

Flatworms are not necessarily uncommon in reef environments, but they can be difficult to find because of their tendency to seek refuge under rocks and rubble. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Flatworms

Many marine flatworms are beautiful creatures with bodies that display brilliant colors and striking patterns that make it easy to understand why some species routinely get confused with a variety of nudibranchs. It is worthwhile to note that flatworms are exactly as their name suggests, flat. While not paper-thin, their bodies are not much thicker than a few sheets of paper stacked on top of each other. Their flat bodies make it relatively easy for experienced eyes to recognize flatworms and distinguish them from nudibranchs and other marine worms.

Surprisingly perhaps to lay people, not all worms, or even all marine worms, are described in the same phylum. All flatworms are members of the phylum Platyhelminthes, a grouping that contains approximately 30,000 species of marine worms. Of these, the vast majority are parasitic and somewhat unattractive, but at least 4,000 exhibit brilliant colors. Divers commonly encounter other species of marine worms including Christmas tree worms, featherdusters and bristle worms. These species are segmented worms described in the phylum Annelida.

Flatworms are non-parasitic, free-living animals. Their bodies are more or less flattened ovals that vary from one to five inches (2.54 to 12.7 cm) in length. There are two small sensory organs on the forward ends of the bodies that look similar to cat ears and that function as antennae. A single opening on the underside of the body functions as both mouth and anus.

Flatworms are not necessarily uncommon in reef environments, but they can be difficult to find because of their tendency to seek refuge under rocks and rubble. While flatworms lack other more developed body functions and systems, they are equipped with primitive eyespots that are bundles of light-sensitive nerves. Extremely sensitive to light, flatworms are typically seen in shaded areas during daylight or when they emerge from under rocks, corals and bits of debris at night.

The leopard flatworm is brilliantly colored with striking patterns. It routinely gets confused with a variety of nudibranchs. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Flatworms are the simplest animals to display bilateral symmetry. This means that their bodies have a front and back, top and bottom, and a right and left side that are identical to one another. Bilateral symmetry is an important evolutionary development in which sensory nerves are concentrated toward one end of the body and this body plan is found in all animals that have specialized organ systems and body parts. This body design is considered to be more advanced than that of radial symmetry, the body plan found in marine animals such as anemones and sea stars. Animals that display bilateral symmetry are typically able to actively pursue their food, seek out mates and escape predation.

Flatworms typically move across the bottom by using tiny beating cilia that line their undersides, and they are sometimes seen swimming in the water column. Some larger species undulate their bodies to assist in swimming.

Flatworms are both scavengers and carnivores with most species also being highly cannibalistic. Some species share a symbiotic relationship, further described as mutualism, with algae that live in their tissues. The flatworms provide a home for the algae and the algae produce food for the flatworms as a byproduct of their photosynthesic processes.

Almost all flatworms are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning each individual possesses functioning male and female sexual organs. In a typical mating event, both animals supply and receive sperm from their mate as the eggs of both individuals are fertilized. Once eggs have been fertilized and are ready to hatch, they are released into the water column and develop into planktonic larvae. In addition to cross-fertilization, flatworms are also capable of asexual reproduction through the regeneration of severed parts.

Headshield slugs and bubble snails are equipped with thin, somewhat rounded, observable shells that have a bubble-like appearance. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Other Opisthos

Other opisthobranchs that are sometimes confused with nudibranchs include some of the creatures commonly known as headshield slugs, bubble shells, sidegill slugs, sacoglossans and sea hares. Headshield slugs and bubble snails are equipped with thin, somewhat rounded, observable shells that have a bubble-like appearance. They also have a body part referred to as a “shield” in the front of their head that is wider than the rest of the body. The shield is used to help them plow through sand when searching for food and to prevent sand from entering and injuring delicate tissues.

Sidegill slugs have relatively thick bodies with two rhinophores on the head and a large, single gill located on the right side of the body between the animal’s mantle and foot. Roughly 20 percent of sacoglossans (also known as sap-sucking sea slugs) have shells while others do not. Only distantly related to nudibranchs, sacoglossans are distinguished from closely related animals by the presence of a single row of teeth on their tongue-like radula, a feature that divers don’t see.

Speaking in generalities, sea hares are opisthobranchs that are larger and have considerably thicker bodies than most nudibranchs. They have generally rounded bodies and two relatively long rhinophores that “stand up” on their head and that are said by those with some imagination to resemble the ears of the terrestrial animals called hares.