When it comes to careers in diving, I think I have been as fortunate as anyone who has ever donned a set of mask, fins and snorkel. After all, in a career that has spanned more than 35 years and 10,000-plus dives, I have made my living traveling the globe with my cameras and pen to help tell the story of the world’s oceans. I am not claiming to have seen or done it all, but my “been there, done that” list is getting pretty long. The beauty of diving is that the opportunities are limitless — I still have a long list of places I want to visit and animals I have not yet photographed.

The Middle of Nowhere

The Middle of Nowhere

One of the places that I want to get to know a whole lot better is a “place” that I often think of as “the middle of nowhere,” although it really isn’t a single place. It is the waters of the open ocean, a “place” often far out of sight of land and high above the seafloor below. No doubt the open ocean is vast, and at times it can seem to be an enormous void, but patience and closer inspection often reveal a fascinating variety of wildlife not often seen over reefs and other sites where sport divers commonly explore. Despite all my years of diving and my intense interest in natural history, in the waters of the open sea it is not uncommon to find myself having no idea how to classify the bizarrelooking creatures I swim with. While some look much like miniature adults of their species, many are larval forms that bear little, if any, resemblance to their adult forms. Other creatures have what are often described as gelatinous bodies. Many are harmless ctenophores and tunicates. Other semi-translucent, gelatinous animals are jellyfishes, or their close relatives. To protect myself against their stings, no matter what the water temperature, I wear a full wet suit, hood and gloves when diving the open sea. Still other gelatinous masses are the eggs of squid and other creatures that inhabit the open sea. But the heart-in-my-throat excitement I always feel — and I do mean always — when freediving or scuba diving in the open sea is not generated just by the presence of tiny larval creatures or gelatinous organisms. That feeling results from the mystery of the unknown — the possibility of encountering some large shark, whale, billfish or other creature that seems to magically appear, literally, out of nowhere. You never know what the deep blue will provide. Sometimes I find myself in a big lifeless world of nothing but salt water. But at other times, every minute or two it seems like I see some lifeform I have never seen before. It doesn’t matter how experienced you are as a diver, when you step off a boat in the middle of nowhere, where there is no land in sight or the closest land is merely a difficult-to-see bump on the horizon, your heart is going to beat a little faster and you are going to feel the excitement in your guts. Out there, the ocean seems huge (it is), and if you are anything like everyone I know who has ever dived the open sea, you will feel insignificantly small and somewhat vulnerable (you are). But it is also alluring, exciting and big-time fun.

My First Times

I made my first open-ocean dives more than 30 years ago in the waters off the Southern California coastline. In those days we “hopped” kelp paddies, meaning we dived under floating rafts of giant kelp pulled loose from the bottom and that were floating on the surface in the open sea far from land. Like other drifting debris, those “rafts of kelp” often attracted schools of yellowtail, dorado, ocean sunfish, bonito and other open-ocean fishes including the occasional blue and mako shark. Sometimes from the surface we could get an idea of what animals might be swimming below a paddy, but jumping into the open sea is always a case of “keep your head on a swivel” and be ready for whatever swims by.

Southern California Shark Dives

Southern California Shark Dives

A blue shark swims in front of a shark cage, a shot taken in the late 1970s in the open ocean off Southern California.

To add to our kelp paddy dives, along with several of my diving buddies I worked as part of a team that began to take shark cages out into the open sea. We did it so we could have a safe place to be when we baited the sharks, as we had learned that on the days when we couldn’t readily find kelp paddies and we just jumped into the water in the middle of nowhere, empty blue water was usually all we saw. After a while we built shark cages and bought bait, and found that could consistently attract and photograph blue sharks and mako sharks. Eventually we began to work outside of cages when attempting to photograph the sharks and other creatures, which ranged from pelagic stingrays to salp chains. Being outside the cage is commonplace with baited sharks in some settings today, but 30 years ago we were on the leading edge of a new adventure in diving.

Hawaii’s Open Ocean

For the past seven years I have served as a photo pro, giving seminars and helping participating divers learn about underwater photography, at the Kona Classic, a spring event in Kona, Hawaii. The Hawaiian Islands are extremely sheer mountains that rise dramatically from the deep seafloor below. Because the islands are so sheer, extremely deep water can be found very close to shore, and several of Kona’s dive operators take advantage of their access to the open sea to venture offshore to look for pilot whales, dolphin pods and oceanic whitetip sharks, among other open ocean inhabitants that routinely cruise near the surface. The waters of the open ocean off Kona have a well-deserved reputation for being exceptionally clear and for being full of marine mammals, sharks and a variety of fishes and other creatures. On sunny days you feel like you can see forever, but by any stretch of the imagination, you cannot see all the way to the bottom. I have never measured the visibility, but I can say that you can often see so far that even large whales and sharks often look tiny in the distance. Diving in such clear water is a magical experience. I find the mystery of the unknown and feeling so small in such a vast ocean always to be both humbling and exciting, and it always makes my heart race with excitement. But I am always able to relax as soon as I see something to photograph. In Hawaii that “something” seems to show up quite often.

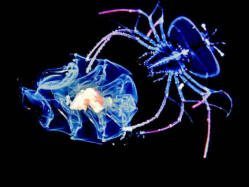

On my dive my biggest score was photographing a larval slipper lobster riding through the open sea on a salp chain. The larval crustacean looked somewhat like a large spider and I was ecstatic to see it.

Black-Water Night Dive

At the recent Kona event I had a chance to dive the open sea at night. Dive leader Matthew D’Avella has made more than 300 excursions into the open sea after sunset where he has filmed some extraordinary creatures, including the pelagic Hawaiian sea horse, larval eels, larval flatfish, a larval broadbill swordfish, numerous deep-water fishes that rise toward the surface to feed in the moonlight, salp chains and myriad invertebrates, including the gelatinous mollusks known as heteropods, ctenophores, siphonophores, shrimps and larval lobsters. On these dives the boat crew deploys a sea anchor — a parachute attached to the boat — into the water to slow down the drift speed of the boat. Most of the divers are tethered to the boat via some safety lines so the divers can’t go deeper than about 40 feet (12 m) and can’t drift away from the boat, but even so, there is something very different and very exciting about stepping off a boat in the darkness of night over a bottom that is more than 5,000 (1,515 m) feet below you. No doubt, a black-water night dive is not a dive for the newly certified or faint of heart, but with proper training and equipment a black-water night dive will open up an entirely new diving universe. So many of the creatures that Matthew and his friends have filmed had never been documented, and that is a huge thrill for everyone who participates. On my dive my biggest score was photographing a larval slipper lobster riding through the open sea on a salp chain. The larval crustacean looked somewhat like a large spider and I was ecstatic to see it. I also saw a variety of comb jellies, numerous larval fishes, and a small fish hiding in a salp chain. Throughout the dive, everywhere I looked it seemed like I was seeing something that was new to me. On numerous sightings I only knew that the organism had a fascinating appearance, but I had no idea what I was seeing. That sort of thing doesn’t happen to me very often these days when diving a reef, but it is a common occurrence when I dive in the open sea. It’s “pelagic magic.” Based on my experiences, the name is truly apropos, not only for the black-water night dive, but for all the dives that take place in the open sea. Ever since I returned home from Kona I have been scheming and plotting about how to do more open-ocean diving. I want to see more big animals swimming through the blue and I want to drift with the planktonic soup in the middle of the night in hopes of photographing another creature that is unknown to me, and perhaps unknown to science. It’s hard to imagine a more exhilarating adventure.

Story and Photography by Marty Snyderman