Normally when I go stargazing, I am outdoors on a relatively clear night, with my face pointed to the heavens and my eyes soaking in the majesty and mystery of the twinkling stars overhead. The Bay Islands of Honduras offer a totally different kind of stargazing that has nothing to do with celestial bodies and is not limited to a nocturnal activity. That is the reason my afternoon dive at Ted’s Point off Utila finds me at 70 feet (21 m) alternately looking between the sandy bottom and the antics of my guide, Captain Nestor Viditto, who is using a rod and one hand to sift the sand all around him. We’re scarcely 10 minutes into this game when Nestor suddenly plunges his probe into the bottom, does a little “I did it” jig and then carefully sweeps his hand back and forth a few inches above the sand like an archaeologist revealing a hidden inscription.

I slowly approach, look where Nestor is pointing and find a pair of tiny black eyes, about 4 inches (10 cm) apart, staring back at me. Nestor gently displaces more sand to uncover two rows of jagged teeth that form a decided frown. I excitedly compose this living death mask in my viewfinder and manage to fire two frames before the Southern Stargazer (Astroscopus y-graecum) bursts from the sand and swims away. I pat Nestor on his shoulder to express my gratitude, and then join him in another victory dance.

Honduras – The Land and Its People

The Republic of Honduras is the second-largest country in Central America and slightly larger than Tennessee in the United States at 43,278 square miles (112,523 sq km). Located on the widest part of the isthmus that bridges North and South America, this diamond-shaped republic is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Guatemala to the west, El Salvador and the Pacific Ocean, via the Gulf of Fonseca, to the southwest, and Nicaragua all along its eastern flank. Honduras also claims small islands and cays in both the Caribbean and the Gulf of Fonseca.

The country is composed of interior highlands and two narrow coastal lowlands that correspond to its Caribbean and Pacific borders. The densely wooded, mountainous interior accounts for 80 percent of its total landmass. Mountain ranges, with peaks to almost 9,500 feet (2,879 m), are intermittently separated by elevated valleys that support farm communities and towns. The Honduras capital of Tegucigalpa is nestled in one of these rich valleys, while San Pedro Sula, the industrial hub and home to the busiest airport, is in the northwest Caribbean lowland.

Hondurans are predominantly mestizos, which means they have a combined heritage of Indian and European extraction. The name does not reveal the manner in which their lineage was mixed. Indigenous tribes originally inhabited the region. Archaeologists dated stone tools found in the area to be more than 6,000 years old and speculated the earliest inhabitants were Paleo-Indians from the north. Mayans later arrived from Mexico and flourished in A.D. 250-900. Indians from the rain forests of Columbia also migrated north and populated the territory.

Christopher Columbus landed near Trujillo in 1502 during his last (fourth) trip to the Americas. He is credited with naming the country Honduras (depth) for the deep waters off its northern coast. Twenty-five years later, representatives of Spain arrived in a much different manner when their king learned rich deposits of gold and silver had been discovered in the Honduran mountains. Spanish forces engulfed the area to extract its valuable resources. When the local population was decimated by slavery and unsuccessful revolts, the Spanish brought African slaves to do the work. A total of 300 years of repression ended when Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua declared independence from Spain in 1821.

The next invading forces were interested in exploiting a different kind of golden or yellow treasure: bananas. The Standard and United fruit companies began battling one another for control of the Honduran banana market in the early 1900s. Bananas accounted for more than 80 percent of the country’s exports by 1930 and the banana companies held tremendous clout. They repeatedly manipulated political scenarios, controlled labor conditions and encouraged the United States government’s involvement to protect its business interests. These companies were eventually bought and the new resulting competitors, Dole and Chiquita, respectively, began using more modern business practices in vying for the title of King Banana.

Tourism, led by scuba divers and nature lovers, has become one of its main sources of revenue. This and other developments have Hondurans looking to the future with hope.

Getty Images

The Athens of the New World

The Mayan civilization is credited with having possessed an advanced understanding of mathematics, astronomy and art. They also developed the only known written language of the pre-Columbian Americas. Copan, known as Xukpi by the Maya, was once a bustling artistic and cultural center that proudly displayed their great achievements for hundreds of years in the seventh century. The restored ruins are located near the Western point of Honduras, only seven miles (11 km) from the Guatemalan border.

The Hieroglyphic Stairway, the most famous discovery at the site, is covered with more than 1,250 carved stone steps and represents the longest Mayan text ever discovered. The 15th ruler of Copan, King K’ak’ Yipyaj Chan K’awiil, had the stairway made to chronicle his accomplishments, as well as those of his ancestors. Only a third of the steps remain in their original positions, so we have no idea what the king did or did not do, but we can appreciate the marvelous craftsmanship.

Sylvanus Morley, a renowned American archaeologist and Mayanist scholar, called Copan the “Athens of the New World” after studying its architecture, hieroglyphs, sculptures, murals and other forms of art. UNESCO apparently agreed with Dr. Morley, as it declared Copan a World Heritage Site in 1980.

In addition to exploring Copan, Honduras offers many different land activities and tours. For example, La Moskitia, along the northeast Caribbean coast, possesses the largest tract of tropical rain forest north of the Amazon. La Moskitia’s Rio Plátano Biosphere Reserve, another UNESCO World Heritage Site, hosts four indigenous groups (Garifuna, Miskito, Pech and Tawahka), as well as hundreds of birds and other animals. You can go bird watching, hiking, tubing, kayaking, boating, crocodile spotting, horseback riding and even dancing. Your local scuba shop or travel agent can help find the right places before, between and/or after your dives.

The Bay Islands

The Honduran government divides the country into 18 departments. The smallest department in both landmass and population is the one that attracts scuba divers from all over the world. The Bay Islands (Islas de la Bahia) Department includes the Bay Islands (the three main islands of Guanaja, Roatan and Utila), Cochinos Cays (two small islands and 13 other cays) and Swan Islands (three islands). These islands lie along The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System that extends north of the Yucatan Peninsula and down to the Bay Islands of Honduras. At 560 miles (896 km) long, it is the second-longest barrier reef in the world (Australia’s Great Barrier Reef comes in first at 1,250 miles [2,000 km]).

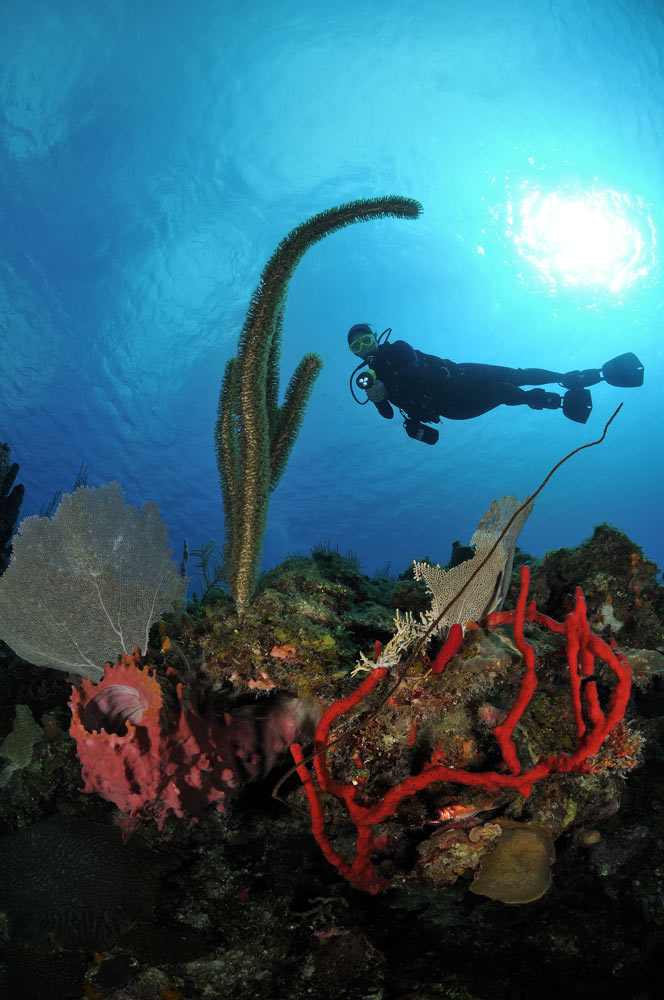

Eager scuba divers need look no further than the Bay Islands of Guanaja, Roatan and Utila. These three islands collectively represent the heart of Honduran diving. The beckoning waters surrounding each island can be explored via live-aboards/safari boats, day boats and shore dives. The sites include wrecks, shark encounters, drift dives, and slow and easy wall explorations and, my personal favorite, shallow-water muck hunts.

The Bay Islands is newbie central. Dive shops cater to tourists who want to get scuba certified. The water is warm, the lodging inexpensive and the instructors plentiful. Sure, I was more than a bit concerned when I thought I might have to share my dives with a bunch of beginners. Fortunately, my worries were for naught. The dive shops also cater to dive snobs like me and maybe you, if the fin fits. Just tell the dive operator your skill level, what you most want to see, how many dives you want to do, if you are interested in night dives and whether you want to dive with a guided group or prefer a buddy team. With enough lead time, most shops will be able to provide you with a dive plan that will make you smile.

Bay Islands reefs hold treasures for all levels of divers. Photo by Scott Johnson.

Roatan

Roatan, the largest (31 miles by 2.5 miles or 50 kilometers by 4 kilometers) of the three islands, used to be the base of operations for more than 5,000 pirates. Now, passionate scuba divers have replaced those swashbuckling buccaneers to seek the natural treasures found at the numerous dive sites ringing the island, such as the Aguila Wreck, Calvin’s Crack and Mary’s Place. Pirate’s Point features an old crane lying in a sand channel near the edge of a colorful wall that descends to 90 feet (27 m). As with most of the Bay Islands sites, I spend the bulk of my bottom time in the shallows. The opportunity to photograph wary, male yellowheaded jawfish (Opistognathus aurifrons) incubating eggs in their mouths and bright red cryptic teardrop crabs (Pelia mutica) clinging to sponges is simply too appealing.

Like many destinations throughout the Caribbean, lionfish (Pterois volitans) have invaded the Bay Islands. Posters in dive shops encourage divers to kill the unwanted fish. A dive guide speared a lionfish at Pirate’s Point and then took it to a scaly-tailed mantis shrimp’s (Lysiosquilla scabricauda) burrow and waited. The large mantis eventually appeared and dragged the entire fish down its hole.

[sam_pro id=1_92 codes=”true”]Guanaja

The least developed, easternmost and second-largest island (11 miles by 3.7 miles or 18 kilometers by 6 kilometers) is Guanaja. Columbus named it the Island of Pines (Isla de Pinos) due to its dense pine forest. While trees decorate Guanaja’s landscape, intriguing wrecks and enticing shallow reefs are its underwater adornments. The bling-bling of swarming silversides makes Jim’s Silver Lode a must. When the energetic, shiny fish are in season, they can be found spilling out of a tunnel in the wall at 65 feet (20 m). It can be disorienting to swim through the dense cloud of tiny fish and then into the open-topped cavern at the other end of the tunnel. This amphitheater is often inhabited by various species of grouper and jacks casually feeding on the silversides.

The artificial wreck of the Jado Trader, a 260-foot (79-m) freighter sunk in 1987, is Guanaja’s signature wreck dive. It lies on its starboard side at 110 feet (33 m) with its bow facing a nearby wall. This photogenic wreck and the generous local divers, who frequently carry food, have attracted a variety of animals to the site. While it is possible to penetrate the wreck, only experienced wreck divers should attempt it.

Southern stargazer. Photo by Scott Johnson.

Utila

Utila is the smallest of the islands (8.1 miles by 3.1 miles or 13 kilometers by 5 kilometers) and the closest to the mainland, which is only 18 miles (29 km) away. Descendants of the original settlers from the Cayman Islands still live on small cays at its southwest point. Utila’s nondescript, relatively flat, sandy typography is mirrored on dive sites like Jack Neal Point. Here, muck diving rules. Gorgeous longsnout sea horses (Hippocampus reidi), ferocious-looking spoon-nose eels (Echiophis intertinctus) and burrowing rough box crabs (Calappa gallus) seem to materialize before your eyes.

Those of you who have visited Sulawesi’s Lembeh Strait or Papua New Guinea’s Milne Bay know real muck diving and are probably wiggling your toes at the thought of finding it so close to the United States. If you’re not familiar with muck diving, think of a weird treasure hunt that takes place on what appears to be barren terrain. In time, patience and a knowledgeable guide can reveal hidden wonders that might just blow your fins off. Of course, that takes us back to the topic of stargazers. I have only seen stargazers at night at other destinations around the world. I was shown them twice during the day within three dives off Utila. Stargazers are absolutely fascinating to study, but be sure you never touch them. They possess special organs near their eyes that can generate an electrical discharge in the neighborhood of 50 volts. I also found Lesser Electric Rays (Narcine brasiliensis) during the muck dives. Like stargazers, these animals can release an electric shock when disturbed.

The Republic of Honduras is a country of incredible beauty and variety. Even more striking are the incongruities that seem to confront you throughout your visit. For example, how can a people that has known such repression throughout its history be so laidback and welcoming to foreign tourists? Or, how can natural resources that have been exploited since the departure of Christopher Columbus still be present in such abundant quantities? While I cannot answer these and many other questions pertaining to the mysteries of Honduras, I do know how to go stargazing underwater during the day. And now, so do you.