This feature story originally appeared in the February 2008 issue of Dive Training to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the iconic television series “Sea Hunt.” In this issue, we have reprinted it to honor the show’s 60th anniversary.

For 60 Years, Diving and Television Have Been the Best of Buddies.

A guy stars in a television show, and millions of people will never look at the world the same way again. At least, that’s what I hear, anyway. I wasn’t there.

Well, actually, that depends on what guy you’re talking about. I do recall the guy in the stocking cap. And I remember the guy in the khaki safari shirt and shorts. But then, who doesn’t? That was practically yesterday.

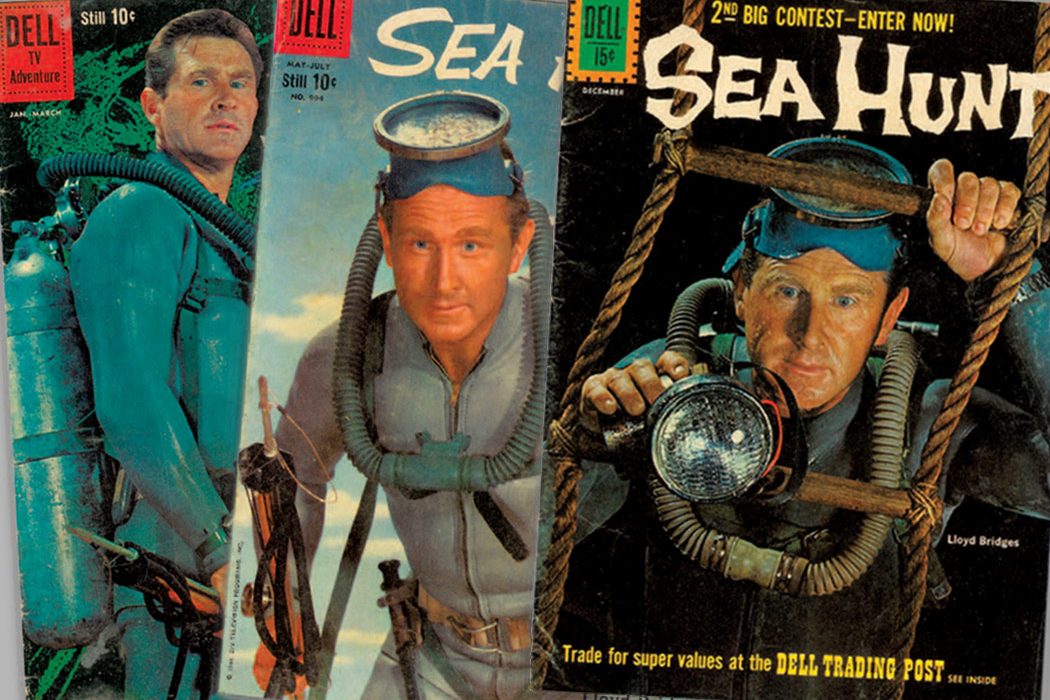

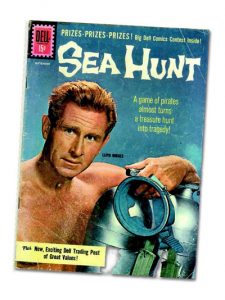

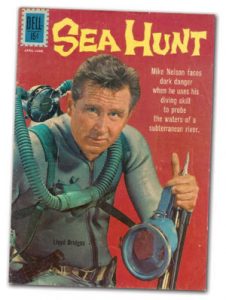

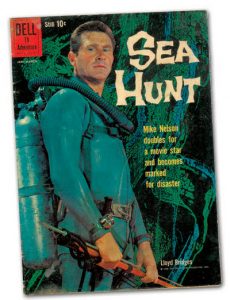

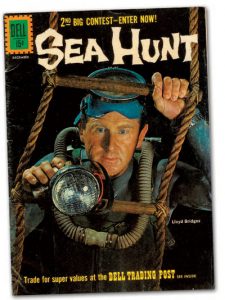

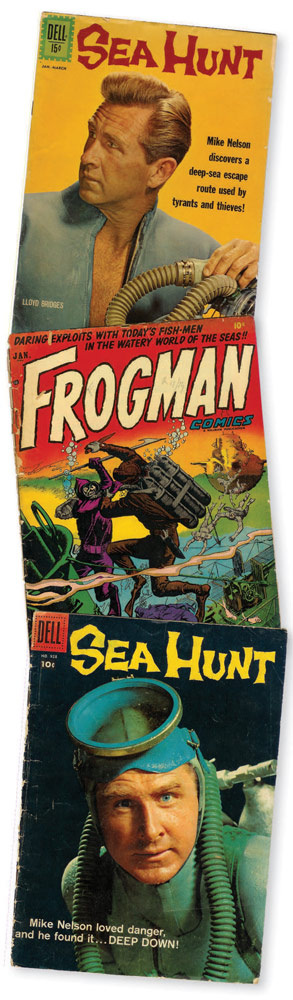

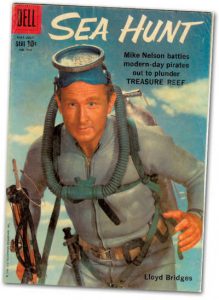

The other guy — some would say, The Guy — is the one with the twin-hose regulator and the silver wet suit, who first graced millions of living rooms 60 years ago this month. And for two generations of scuba divers, he’s the best way to make their eyes light up like a kid at Christmas. All you have to do is mention Mike Nelson and “Sea Hunt,” and they’re back in their childhood, swimming alongside the underwater investigator, solving crimes and wrestling octopus.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this show gave the fledgling scuba world the gentle kick in the butt it needed to leave the nest. It was — is — a phenomenon.

“It wasn’t just the diving, it was the ocean, and those kinds of things,” says Robert Thompson, director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and co-author of “Television in the Antenna Age.” “That was one of those shows that really gripped you.”

Or at least it did for somewhere between 1.5 million and 2 million divers, who were inspired to take to the underwater world for themselves, says Kent Rockwell of the Historical Diving Society. That means if you didn’t first slip on a mask, fins and regulator “to be like Mike,” then our buddy or your instructor or the guy next to you on the dive boat did.

But for every diver inspired by “Sea Hunt,” these days there are two or three more who are acting out other stories that they grew up with. And chances are, those stories came in the form of one television show or another. After all, diving and television have had a long relationship. In a way, this occasion marks the anniversary of that, too.

Sea Hunt: Television History

“There were a lot of half-hour adventure shows that seem to have been forgotten,” Thompson says. “‘Sea Hunt’ seems to have really carved out a niche in the hearts of people who saw it.”

And why wouldn’t it? It offered adventure, good versus bad and a glimpse of the world that few people had ever seen — the world underwater, and while it wasn’t the first underwater show, it is the one we remember. But that success didn’t come easy. Creating such a show early in the days of television had more than its share of challenges, but it left a legacy felt in Hollywood for decades.

For the uninitiated, here’s the executive summary: In 30 minutes, the crooks — they’re the ones in the dark wet suits — do a misdeed. Our hero, Mike Nelson, gets into trouble, gets out of trouble, rescues a damsel in distress — typically played by co-star and diving legend Zale Parry — and, finally, catches the bad guys in the act. In the process, someone’s regulator hose invariably gets cut in an underwater tussle.

This went on for 156 episodes between 1958 and 1961, and viewers who missed it the first time through could relive the drama during the show’s heavy rerun cycle throughout the ’60s and ’70s. Not that very many people missed that first showing. Within its first nine months, it ranked No. 1 in ratings, with an average 50 percent share of audiences in 50 major cities. In New York City, it averaged 59 percent of the audience. The show had similar audiences in other countries, including Australia, United Kingdom, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Philippines and Japan. Legendary executive producer Ivan Tors estimated that 40 million people watched the show on a weekly basis.

This went on for 156 episodes between 1958 and 1961, and viewers who missed it the first time through could relive the drama during the show’s heavy rerun cycle throughout the ’60s and ’70s. Not that very many people missed that first showing. Within its first nine months, it ranked No. 1 in ratings, with an average 50 percent share of audiences in 50 major cities. In New York City, it averaged 59 percent of the audience. The show had similar audiences in other countries, including Australia, United Kingdom, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Philippines and Japan. Legendary executive producer Ivan Tors estimated that 40 million people watched the show on a weekly basis.

That saturation had nearly everything to do with its legacy. It also has everything to do with the fact that there will never be another show like it again.

“Back then, there were only three networks — there wasn’t that much on, so it was pretty hard not to stumble on it,” Thompson says. “When ‘Sea Hunt’ was out, it didn’t have to be that competitive — we’re talking about three different networks, and you might have an independent station or two in your market — but there weren’t that many choices out there.”

The only thing it doesn’t have: virtually no existence in reruns. That means if you didn’t see it then, or you don’t have one of the DVD collections that are available online, or you don’t dive out of one of the local dive centers that host “Sea Hunt” film festivals during the winter months, you probably don’t get it. Don’t worry; a lot of us don’t. Those who do say you had to be there, which is doubly true if you have a hard time picturing Lloyd Bridges in anything other than “Airplane” or “Hot Shots!”

As it was, Tors took a gamble to create the show. Shooting on location at sea was both difficult and expensive, and the major networks figured a weekly 30-minute show was bound to run out of material, so they turned down the chance to sign on. Tors’ final option was shopping the show to Frederic Ziv, the undisputed king of syndicated television and radio. Ziv suggested skipping the networks entirely and selling the show directly to local TV stations. Ziv was dead-on right. He recognized it for what it was — a repackaging of the chase formula he had practically patented. While “The Cisco Kid” was a chase on horseback, and “Highway Patrol” was a chase in cars, “Sea Hunt” was a chase underwater.

And that’s where Bridges fit right in. As a concept, Tors preferred the action photography to be the “star,” not some big-dollar actor. Besides, a mask would cover the star’s face most of the time anyway and, in filming, body language was more important than star quality. Not that Bridges was a slouch. He’d had some early success in movies — starring in “High Noon” with Gary Cooper, “Sahara” with Humphrey Bogart, and “Plymouth Adventure” with Spencer Tracy, but he’d been blacklisted by Sen. McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee because of some youthful indiscretions. He needed the work, even if it was just television.

And that’s where Bridges fit right in. As a concept, Tors preferred the action photography to be the “star,” not some big-dollar actor. Besides, a mask would cover the star’s face most of the time anyway and, in filming, body language was more important than star quality. Not that Bridges was a slouch. He’d had some early success in movies — starring in “High Noon” with Gary Cooper, “Sahara” with Humphrey Bogart, and “Plymouth Adventure” with Spencer Tracy, but he’d been blacklisted by Sen. McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee because of some youthful indiscretions. He needed the work, even if it was just television.

That worked perfectly for Ziv. For his part, he wanted a single, strongly motivated character who portrayed a singular moral philosophy. “Let’s face it, it was a formula kind of adventure kind of show,” Thompson says. “But there was an earnestness about it that’s completely changed in the way we see many of these things presented today.”

And, as an early television series, “Sea Hunt” was a vehicle that allowed a slew of Hollywood types to cut their teeth in the art. Bridges would go on to the “Lloyd Bridges Show” and “Daring Game” series on television, as well as an occasional cameo on such programs as “Seinfeld,” plus the movie “Tucker,” which starred his son, Jeff. He completed two additional movies shortly before his death in 1998, including one with son Beau. Incidentally, both Bridges boys made their acting debuts on “Sea Hunt.”

And then there’s cameraman Lamar Boren, who went on to work with Tors on “The Undersea Warrior” and “Flipper,” and who would receive an Academy Award for underwater cinematography for the James Bond film, “Thunderball.” Associate producer and director John Florea would go on to direct, write and produce more than 600 films for television. Director Ricou Browning eventually directed “Flipper” episodes and did stunt work for “Thunderball” and “Never Say Never Again.” Actor Robert Ridgely had roles in “Get Smart,” “Coach,” “Blazing Saddles” and “Philadelphia,” and producer Maurice Rifkin would produce “Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau” and National Geographic specials in the 1960s. And there were countless others. Leonard Nimoy, who would soon be known forever as Dr. Spock, was even cast in a couple of episodes.

Illustration by Keith Ibsen

After Mike

Yet, for all of its colorful history — and for the long-term effect it had on the kids curled up to watch it — “Sea Hunt” was pretty black-and-white thematically. As a result, many modern viewers will find the nostalgia for the show to be more satisfying than the show itself. It was a pretty benign formula, almost completely devoid of the plot twists and crazy characters that we’ve grown accustomed to from modern television. Both the medium and the market for television has changed dramatically in the past 60 years, as have the technologies and the techniques entertainment-types use to tell stories.

“Sea Hunt” was, ultimately, a creature of the times. It had a pretty simple moral message: The good guy fought the bad guys, and the good guy won. This was the 1950s, after all, with Ozzie and Harriet, and all that. For heaven’s sake, Lucy wasn’t even allowed to say “pregnant” the season she was with-child just a few years earlier.

Ironically, the story goes that the show ended because Bridges felt hemmed in by these simple plot lines. He was aware that pollution and other man-made problems were affecting the coast, and he wanted to attack the “real villains,” like the oil companies. Mind you, Standard Oil was one of the “Sea Hunt” sponsors, so that was going nowhere. And so it goes.

As one 1950s adventure show’s star set, another one rose, doing more or less what Bridges wanted to do in the first place. And at the same time, the true colors of the ocean finally made their way onto the television screen.

To fill in some history, RCA rolled out the first color television in 1954, an event that met with a resounding thud. With a $1,000 price tag, the novelty box was as pricey as a new car, and, to make matters worse, there wasn’t any full-color programming for it. Of course, it was compatible with black-and-white programming, but then, so were black-and-white sets. As a result, there wasn’t much of a market for it.

RCA decided it needed to do something about the lagging color set sales, so in 1961, it courted Walt Disney away from ABC to NBC, the network it owned. “Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color” had an immediate effect on color set sales, and by 1966 NBC would become the first all-color network.

Actually, Tors considered shooting the show in color, but chose black and white because that film offered better image quality in the underwater action sequences, Rockwell says. He figured the expense wasn’t worth it, given the low “saturation” of color televisions in viewers’ homes at the time. Rockwell wonders if the show would still be in syndicated reruns if Tors had decided differently.

But he didn’t, and a retired French Navy captain did. Indeed, thanks to color television, the red watch cap would forever become an icon.

“Jacques Cousteau was really an important presence in television — for one thing, he was on a lot,” Thompson says. “Cousteau and his production company never forgot that they had to make these things entertaining. They certainly had narrative threads — they weren’t necessarily narrative threads of good versus evil, with one of them triumphing in the end, however — they were more of these narrative threads of the story of exploration and discovery and the gaining of knowledge, and seeing things we hadn’t seen before — and getting it on camera.”

Even Cousteau admitted he didn’t make documentaries. “We are adventure films,” he told The New York Times. By doing so, he — and the color images he showed — opened our eyes to the Technicolor reality of the underwater world. And people noticed. He received his first Academy Award for “The Silent World” in 1956 and the next for “World Without Sun” in 1964. He would eventually win another Oscar, plus 10 Emmys, and numerous other awards for his work, but more importantly his early success led to a multimillion-dollar deal with ABC to produce four hour-long specials a year for more than nine years. And that meant for the next two decades, if you had a television, you knew Cousteau — and you knew him at nearly the same time as consciousness for the environment was ascending into its own sphere of influence. Indeed, The National Geographic Society — a longtime sponsor of his expeditions — once called Cousteau the “Rachel Carson of the Sea.”

But more importantly than advancing the art of television documentaries or raising awareness for preserving the marine world, Cousteau showed you didn’t need to look like a Western hero to become a diver. Even the motto for the Calypso was an accessible “We must go and see for ourselves.”

And that, if anything, may ultimately have led to his cinematic undoing, as showmen took mainstream diving to the extreme — we are, of course, talking about the late Steve Irwin and his ilk, which happens to include two grandsons of Cousteau. When television became rife with nature shows, it was harder for him to create the same sense of wonder of his early work. He moved from network to PBS, then to cable. That’s sort of emblematic of television itself, according to New York Times critic Julie Salamon.

“The engine that’s constantly running this whole operation is the desperate search for audience,” Thompson says. “By the time the Crocodile Hunter comes around, you’ve got all these cable channels, which is an advantage, because there’s room for guys like that.”

But in order to pull it off, networks had to scramble to get people to pay attention amid all these other options. It’s kind of like diving, really. When it’s the only game in town — or when that game is made extreme because you built your gear in your garage like many of Mike’s early fans did — it doesn’t need a hard sell. But when you’ve got the choice between diving and, say, paragliding, jet-skiing, wake-boarding, deep-sea fishing, luxury kelp-wrap facials, and an all-you-can-eat buffet, it’s a little harder for one activity to capture your attention.

But in order to pull it off, networks had to scramble to get people to pay attention amid all these other options. It’s kind of like diving, really. When it’s the only game in town — or when that game is made extreme because you built your gear in your garage like many of Mike’s early fans did — it doesn’t need a hard sell. But when you’ve got the choice between diving and, say, paragliding, jet-skiing, wake-boarding, deep-sea fishing, luxury kelp-wrap facials, and an all-you-can-eat buffet, it’s a little harder for one activity to capture your attention.

So, you add sea monsters. Sharks.

Enter shows like “Ocean’s Deadliest” and “Shark: Mind of a Demon,” which, incidentally, star Irwin and Philippe Cousteau and Fabian Cousteau, respectively. It helps to understand that we have a 150-year-old tradition of adventurers returning from expeditions to the jungle to give lectures in dime museums and vaudeville houses, Thompson says. In that sense, these shows can draw direct lines of lineage to carnival freak shows, where musclemen wrestled crocodiles or where folks paid 50 cents to see shriveled Feejee mermaids. These shows became a hit, partially because they appeal not only to someone who was looking to be enlightened, but also to all those 8-year-old kids who thought it was just fun to watch.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Technology, Again

Television and diving are more intimate partners now even more than in the days of Cousteau. The fact is, people like to watch this kind of stuff, and that’s not likely to change, either. Not only do viewers have their choice of niche channels to watch, they’re also driving technological changes in how those programs are broadcast. Just as the introduction of color television changed programming, the advent of digital cable and high-definition broadcasting is changing our appetite for eye candy with every new plasma and LCD television sold. The question is whether a “Sea Hunt” would be as popular now as it was then. As it turns out, it already is. It’s just not what you think.

Television and diving are more intimate partners now even more than in the days of Cousteau. The fact is, people like to watch this kind of stuff, and that’s not likely to change, either. Not only do viewers have their choice of niche channels to watch, they’re also driving technological changes in how those programs are broadcast. Just as the introduction of color television changed programming, the advent of digital cable and high-definition broadcasting is changing our appetite for eye candy with every new plasma and LCD television sold. The question is whether a “Sea Hunt” would be as popular now as it was then. As it turns out, it already is. It’s just not what you think.

“Once we started juicing up the competitive nature of television — when cable moved in, and we’ve got all these other niche market networks — programmers looked to various things they could make exciting, and the whole schlockumentary, reality- TV stuff starts moving in,” Thompson says. “There are thousands of years of traditions of sea monsters and sharks, and all that other kind of stuff, so there is certainly an element of excitement, and I think that’s probably why this extreme stuff picked up on it.”

These days, by Discovery Channel’s own admission, it doesn’t care if the climbers in the reality program summit Mount Everest, or if the storm chasers manage to drive their armored car into a Midwestern tornado with cameras rolling, or even if Fabian Cousteau’s shark-submarine actually works. They — and their slice of the audience — want drama, and drama necessitates mishaps, and conflict, and tension. Otherwise it kind of sucks as an adventure, you know?

And while the kinds of stories that get told have changed, so has the means by which they’re told — and, ironically, in some cases that’s even removing the need for a story in the first place. Just as RCA gigged Disney into producing programming for the early adopters who purchased color televisions, networks are scrambling to provide programming to owners of HDTVs, which are now tuned in by about 32 percent of U.S. homes, according to the Consumer Electronics Association. The results include “Sunrise Earth,” a new, high-definition program that airs on Discovery Channel HD Theater channel, and that features — sit down for this — sunrises in breathtaking digital color. It will soon be joined by the Smithsonian Channel, “Expedition Safari” on Versus Network, CNN HD-specific feature programming, and the one I’m holding out for, “Aerial America,” which will give viewers a bird’s-eye view of various parts of the United States when it debuts this summer. By the end of the year, there should be more than 50 high-def channels offering a variety of programs. That’s not just wishful thinking; the FCC has ordered all broadcasters to replace analog signals with digital before February 17, 2009.

You can bet a sizable quantity of these new “pretty picture programs” will feature the underwater world. How do I know? Check out Discovery Channel’s series “Planet Earth.” It’s sold more than 170,000 copies on high-definition video discs, at $100 a set, making it the top revenue-generating HD title so far.

And, of course, all this begs the question of a future “Sea Hunt.” Thompson suggests it depends on what you’re looking for. In their original forms, both Mike Nelson and Jacques Cousteau look dated now, but documentaries obviously haven’t gone away, and neither has formula television.

By way of a sidelong example, forensic science shows have been around since Jack Klugman played “Quincy, M.E.” in the 1970s. These days, that same formula draws big viewers to the “CSI” franchise — “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation,” “CSI: NY” and “CSI: Miami.”

The nearest anyone has come to resurrecting a mainstream diving drama was Steven Spielberg’s project, “seaQuest DSV” in the early 1990s that withered on the vine for three seasons, though I can’t say I ever watched it on purpose. But because it’s off the Big Three of television drama — cops, lawyers and doctors — diving is a hard sell. Those themes offer the built-in theatrical drama of life or death. And while “Sea Hunt” did that for 1950s audiences, it seems a little tame now. That’s the difference between the diving world including a couple of thousand divers then, and a couple of million now. That’s awareness for you.

And in a way, the progression from drama to documentary to farcical reality may be a pattern for television. Case in point: First there was Quincy, then there were crime documentaries like “American Justice,” and now there are perpetrator-baiting shows like “To Catch a Predator.” Soon, there will be a Crime and Investigative satellite channel. Stop me if this sounds familiar. Even as silly as some of those shows are, they’ve boosted forensic program enrollment in both American and British colleges that offer forensics degrees.

And that means there will always be another “Sea Hunt,” in the metaphorical sense. While it inspired millions of people to dive, there’s nothing to say that even these programs don’t plant the seed that will eventually grow into the desire to dive. “Both ‘Sea Hunt’ and ‘Jacques Cousteau’ were always simply a first step, an inspiration, and I think ‘Crocodile Hunter’ and ‘Shark Week’ could do that as well,” Thompson says. “You could be watching one of these really exploitative documentaries and enjoying the kind of razzle-dazzle of the whole thing, but it could also make you become really fascinated with sharks, and whatever you do after that you can still trace your interest back to ‘Shark Week,’ but you mature beyond that.”

And that means there will always be another “Sea Hunt,” in the metaphorical sense. While it inspired millions of people to dive, there’s nothing to say that even these programs don’t plant the seed that will eventually grow into the desire to dive. “Both ‘Sea Hunt’ and ‘Jacques Cousteau’ were always simply a first step, an inspiration, and I think ‘Crocodile Hunter’ and ‘Shark Week’ could do that as well,” Thompson says. “You could be watching one of these really exploitative documentaries and enjoying the kind of razzle-dazzle of the whole thing, but it could also make you become really fascinated with sharks, and whatever you do after that you can still trace your interest back to ‘Shark Week,’ but you mature beyond that.”

One of the glories of television is that it introduces us to all of these other environments that we would have never experienced otherwise. “You may have a 10-year-old, laying about the house, who knows sharks exist, but never gave them much thought one way or the other,” Thompson says. “They watch a bunch of ‘Shark Week’ programming and they become really interested in sharks. So they might get a shark book, or take a class in high school, or whatever. Television is really good at introducing us to things that we may not have otherwise thought of, but usually it’s not very good at taking us past that 101 level of introduction.”

And if the history of “Sea Hunt” is any indication, television will whet its viewers’ appetites for the underwater world for decades to come. That means future generations of divers may not necessarily want to wrestle an octopus, but they’ll certainly crave seeing one for themselves.