If you watch a group of scuba divers as they begin a dive, you likely will see them enter the water and make a dash for the closest reef, kelp forest or wreck. If they come across any stretches of sand or rubble their intent is usually to get past the area as quickly as they can so they can get to “the good stuff.” If this describes you, I suggest that sometimes on the way to or from the reef, kelp beds or wreck, you allow yourself sufficient air and bottom time to spend a few moments exploring the sand and rubble looking for animals you are unlikely to find anyplace else.

Let me be clear here: Often the assessment that the sand and rubble won’t produce as many interesting animals is right on the money. Those areas often appear devoid of life, and even when you do discover a sand or rubble critter, many are less interesting or colorful as their counterparts in other marine communities.

But sometimes the sand and rubble are magical kingdoms filled with bizarre-looking creatures and fascinating animal behaviors. While you might not always want to spend a lot of time exploring this zone, most experienced divers will advise you to not overlook these distinctive and diversified areas. In fact, one of the more popular types of diving experienced divers enjoy more and more is known as “muck diving,” an activity that is all about searching for bizarre-looking creatures such as flying gurnards, hairy frogfish and waspfish as well as invertebrates such as the mimic octopus that inhabits soft-bottomed “out in the middle of nowhere” areas of sand and rubble.

With sand and rubble zones lacking structures that offer protection and hiding places, it makes sense that many sand creatures are excellent burrowers. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Who Wants to Live in the Middle of Nowhere?

The bodies of many creatures that inhabit the sand and rubble have an extremely low profile, a trait that makes perfect sense when you consider that a major difference between crevice-filled reef habitats and the sand or rubble is that while reefs are a latticework of hiding places, there are very few places to hide in the sand. With the sand and rubble zones lacking structures that offer protection and hiding places, it makes sense that many sand creatures are excellent burrowers, able to bury themselves rapidly when exposed, able to stabilize the substrate around them, or extremely cryptic and able to blend well with their surroundings.

As examples, many species of crabs and clams are superb diggers. In fact, clams spend long periods buried in the sand with only their paired, tube-like siphons exposed. The siphons enable clams to take in oxygen-rich water and food as well as eliminate waste without having to expose their soft bodies to danger. Many shrimps and even a surprising number of fishes such as some flatfishes, razorfishes, cusk eels, snake eels and stargazers also spend a lot of time buried in sand or rubble.

Being buried not only helps many sand dwellers avoid detection from predators, but it also helps species such as stargazers and angelsharks go undetected by their prey. When unsuspecting fishes and invertebrates accidentally enter the “strike zones” of these well-hidden predators, the hunters quickly explode out of the sand and capture their shocked prey in the blink of an eye.

Other sand residents such as sea pens, the common name given to a group of often gorgeous colonial animals described in the phylum Cnidaria, often withdraw into the sand when currents are slack but emerge and use their stinging cells to stun and capture prey floating in the water column when the food-filled currents are running. If uncovered when buried, sea pens can quickly rebury as can many sand-dwelling crabs, shrimps, worms, heart urchins, brittle stars and fishes.

Sea pens often withdraw into the sand when currents are slack but emerge to feed on tiny prey floating in the water column where currents are strong. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Burrowing In

Other sand and rubble residents such as jawfishes, tilefishes, garden eels, mantis shrimps, tube anemones and some octopuses reside in self-made burrows that can be used as homes and places of protection. Some of the burrow-dwelling fishes are constantly popping their heads out of their burrows to feed, to try to woo a mate and to check out their surroundings, providing a jack-in-the-box-like show for observant divers who don’t crowd these burrow dwellers, forcing them into retreat in their subterranean homes. In jawfishes, males construct the burrows, and they are fastidious about maintaining a clean home. These diligent workers constantly arrange, rearrange and move the debris that lines and lies near their burrows.

The bodies of many creatures that inhabit sand and rubble have an extremely low profile, such as this flatfish, known as a turbot. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Duck and Cover

Razorfishes and several other sand residents avoid the labor of building and maintaining a burrow, because they can quickly evade predators by darting into the sand deep enough to get out of sight. A variety of species of snake eels also do an amazing job of maneuvering and hiding in rubble zones. Their strong, sharply defined tails enable them to wriggle backward and rapidly bury themselves in sand and rubble. The long, slender bodies of snake eels are generally spotted and have highly prominent nostrils protruding from their head. Although they occasionally swim along the seafloor during the day, snake eels tend to remain buried during daylight hours while emerging at night to forage along the bottom.

Being buried not only helps many sand dwellers avoid detection from would-be predators, but it also helps species such as stargazers and angelsharks go undetected by their prey. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Not All Sand-dwellers are Small

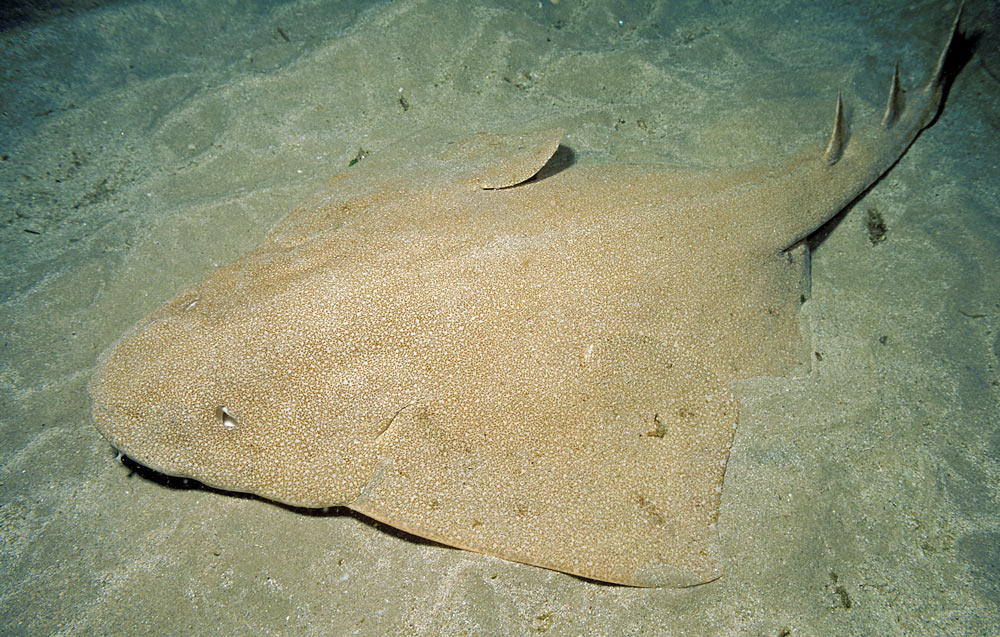

Some of the more noteworthy larger species include angelsharks and a variety of rays. Worldwide there are 13 species called angelsharks. All are flat-bodied sharks often thought to be some kind of ray. Certainly angelsharks have greatly modified, enlarged pectoral fins that look a lot like the wings of many rays, and from afar they don’t seem to look much like sharks. Angelsharks have a blunt snout and their well-camouflaged bodies blend well with the sand.

Angelsharks routinely bury themselves in sand, leaving only their eyes, spiracles and the top of their head exposed. The spiracles are valve-like openings near the top of the head that allow these sharks when respiring to take in oxygenated water that has much less debris than the sharks would have to deal with if their gill openings were on the sides or bottom of the head, portions of the body that are often buried in sand and bottom debris. When hunting, angelsharks routinely wait patiently for an unsuspecting fish, squid or other prey item to enter their “strike zone,” an area only a few inches above and in front of their mouth, before exploding out of the sand, quickly opening their mouth much wider than you would likely think they could, and capturing their prey before it has a chance to react.

A number of large rays including the majestic spotted eagle ray, the southern stingray, an animal that is often encountered on sand flats from New Jersey to Brazil and throughout the northern Caribbean, and the bat ray, a graceful swimmer found along the west coast of North America from Oregon to Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, are commonly seen in various sand communities around the world. When feeding, these rays grub, or dig, through the sand looking for worms, mollusks, crustaceans and some small fishes hidden in the sand. When hunting they use their large snouts to dig through the sand, and they are also known to “flap their wings” to expose hidden prey. Like their close cousins the sharks, skates and other rays, stingrays are equipped with highly specialized gel-filled pit organs known as ampullae of Lorenzini that help them detect the electrical fields emitted by prey hidden in the sand. They use this ability with their keen sense of smell to detect prey.

When at rest, stingrays often bury themselves in the sand leaving only their eyes and spiracles exposed. Wise divers pay heed and make the worthwhile effort to avoid settling on top of stingrays, as these rays are armed with one or more knife-like, venomous barbs near the base of the tail.

Some are Shocking

A number of species of rays that inhabit the sand biome in all temperate and tropical seas are called electric rays. Like all other rays they are cartilaginous fishes, meaning their bodies lack bone, but unlike other rays, electric rays have the amazing ability to create electricity. The voltage they create varies from species to species and shock to shock, but specialists say that the voltage typically ranges from 30 to almost 220 volts, a jolt powerful enough that it should sufficiently warn snorkelers and divers to pay heed.

Electric rays produce electric charges in self-defense and to capture prey, and some specialists believe the electricity-producing organs might also be used in intraspecies communication, helping individual rays of a given species “talk” to one another.

The kidney-shaped electric organs are midway between the start of the tail and tip of the head on each side of the body. Creating an electrical jolt requires considerable energy expenditure from the ray, and it takes some time to create another follow-up blast. During the short recharging phase, the animals are vulnerable. The good news here is that being vulnerable is dangerous, and electric rays don’t waste their shocks. They aren’t likely to swim up to divers and snorkelers and shock us just because they can. When the rays deliver shocks the electric jolts come in short pulses and quickly weaken in intensity.

The diet of electric rays consists primarily of a variety of bony fishes. When hunting, electric rays pursue and stun prey but usually wait for prey that chance upon them. Sometimes they hover close to the seafloor as they slowly search for prey. On other occasions the rays employ an ambush strategy in which they bury themselves in bottom sediment and wait for unsuspecting prey to swim by. In this case, the rays typically stun the prey first by shocking and then try to grab the prey in their mouth.

While it can be difficult to predict whether a dive over the sand and rubble will be one of feast or famine, there are definitely some great dives to be enjoyed in these areas. Check with your instructor, divemaster and other local experts, and if they indicate that exploring an area of sand or rubble often makes a good dive, then give it a go, but move slow and keep an ever watchful eye out for a variety of captivating creatures.