The fish, a spectacularly colored grouper, paused and opened its mouth. Finning only slightly to maintain its position just a foot (30 cm) or so above the reef, this brightly colored red and blue-spotted grouper waited patiently for another fish, a cleaner wrasse, to provide its services. Within only a few seconds the cleaner approached and went to work, moving from the tail toward the head along the grouper’s body. The cleaner paused every few seconds to pick at the skin of the grouper.

Like other cleaner species, cleaner wrasses help rid groupers and other host animals of irritating ectoparasites that can be found on the skin of the hosts. In doing so the cleaners gain a meal while the host benefits by getting cleaned.

My dive buddy and I followed the grouper as it slowly moved down the reef. We watched as another fish, the same general size and shape as the cleaner wrasse, appeared. Looking quite confident that additional cleaning services were about to be rendered, the grouper paused and opened its mouth. In the blink of an eye, the fish I thought was a second cleaner wrasse swam up and bit a chunk of skin out of the side of the obviously startled grouper.

Clearly, the attacker was a mimic, a species that does a good enough job of imitating a cleaner species to fool groupers and other fishes into thinking the mimic is the real deal. It’s a risky business to try to fool well-equipped predators, but if well-done, the act of deceit can provide a mimic with a meal. If done badly, no more meals will be necessary. This mimic was a tiger blenny, a fact that, like the grouper, I realized only after the daring blenny had enjoyed its success.

After the dive I excitedly asked my diving buddy what she thought of the scene we had just witnessed, and much to my surprise, her only comment was, “that big fish sure is pretty.” At first I thought she was putting me on, but I soon realized that she had missed both the cleaning and the attack. She had noticed that the grouper had its mouth open rather wide, but she wasn’t sure why. She thought the fish might have been injured.

Observing marine life is like putting puzzle pieces together. When you look at one fish, you see only one piece of the puzzle. Yet when you connect the pieces — say a fish to its habitat and to other creatures within that habitat — you begin to see the inner workings of a marine ecosystem.

But how does one go from fish watcher to underwater naturalist? First, the more you dive, the more you will begin to see various subtleties, and the better observer you will become. You’ll find that your awareness of the underwater world increases with time, the number of dives and the variety of habitats you get to explore and enjoy. Second, it helps to learn about what’s going on under the waves so you are more likely to recognize the happenings that you encounter during your dives.

Find Out Who Lives Where, and Why

Find Out Who Lives Where, and Why

When looking for a particular marine animal, it helps to know where to find it. Marine life identification books and regional dive guides are excellent resources for learning what types of animals you’d expect to see in a given area. Water temperature and geographical distribution are key factors in determining which species live where. For example, you aren’t likely to see a blue shark on a tropical reef. Blue sharks tend to inhabit the cooler waters of the open ocean in temperate, not tropical, seas. Conversely, you aren’t likely to see an angelfish in a California kelp forest. Angelfishes require warmer water.

Those examples might sound obvious, but being aware that within the same geographical area there are a variety of habitats, and that different groups of animals typically occur in different marine ecosystems isn’t as readily apparent to beginning divers. Keeping these facts in the forefront of your diving mind can be very helpful when it comes to becoming a better observer of marine life.

After all, it makes sense that fishes and other animals that inhabit the sand possess a different set of adaptations than do animals that inhabit reefs or live in mid-water. But because most of us haven’t had a ton of ocean experience when we first take up diving, it can be helpful to have this type of information pointed out to us.

For example, many sand dwellers have extremely low profiles. With few structures that offer hiding places in the sand biome, it should not be surprising to learn that most animals that live in the sand are excellent burrowers, able to rebury themselves rapidly if they get exposed, able to stabilize the substrate around them so they can remain in one place, or they are masters of camouflage. The behavior of creatures such as sea pens, tube anemones, clams, sea stars, sand dollars, stingrays, angel sharks, razorfishes and flatfishes illustrate these points.

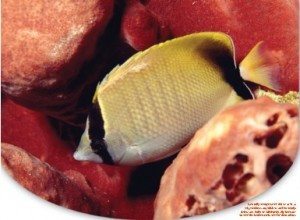

In contrast, most reef inhabitants are better equipped to maneuver in the tight confines of a reef, grip the substrate, or blend into backgrounds of varied patterns and hues. Thin-bodied butterflyfishes, angelfishes, sea fans, crinoids, sculpin and other multicolored striped, spotted and mottled fishes provide classic examples that illustrate these adaptations.

Animals ranging from jellyfishes to sharks, whales, dolphins, manta rays, billfishes and tunas are better equipped to inhabit the open sea. Most fishes that live in the open ocean are designed to be superb cruisers but they lack the maneuverability of many reef fishes, and creatures such as jellyfishes would certainly be injured if they were constantly bumping into hard reefs.

On a tropical reef, the creatures encountered on the reef flat, top of a wall, shallow wall and deep wall are often different. This fact might not be so obvious the first few times you explore tropical reefs. If you are like most divers, it takes a while to get your bearings and know where you are in a reef ecosystem, much less to begin to positively identify and distinguish various species and to recognize behaviors.

In fact, I think it’s fair to say that to new divers, many marine creatures look alike. And just as a lot of marine creatures seem to look alike when you first begin to dive, it is not always immediately that different niches exist. In other words, the various niches in a coral reef kingdom or kelp forest can look the same to divers when we lay eyes on coral reefs and kelp beds for the first time. The good news is that it doesn’t take long to begin to get oriented and to recognize that different species occupy different niches within a larger ecosystem.

If you pay attention, as you gain experience you will quickly realize that the animals that occupy one niche are often different from those that occupy another niche only a few yards away.

For example, in many tropical reef systems you are likely to see schools of tangs and surgeonfishes along the tops of reefs, but you aren’t likely to find them in deeper areas. At the same time you are likely to find creatures such as lobsters, crabs, shrimps and octopods close to areas that are filled with cracks, crevices, ledges and other hiding places.

While there are way too many species to mention, you want to realize that the ocean, and even a single reef area, is not just one generic place. There are many different habitats, and different species tend to occupy the various habitats.

Of course, as soon as I make that point, I must point out that there are plenty of exceptions to that general rule. For example, you might see a school of feeding jacks, eagle rays or a reef shark cruising various niches in a reef system.

Divers that explore temperate seas will find that a variety of habitats exist in kelp forests as well as in the rocky reefs. Close to 800 species inhabit Southern California kelp forests, but different creatures live in the floating canopy near the surface, on the fronds, on and around the holdfasts, in and on the surrounding reef, in mid-water and on the nearby sand flats.

While you might encounter creatures that range in size from inch-long, rainbow-colored nudibranchs to lobsters to giant seabass on a single dive in a California kelp forest, the odds are high that you will find various species in different parts of the forest and surrounding habitats.

Consider Form and Function

Consider Form and Function

The body shape of marine creatures plays a very important role in how and where various species live.

As examples, most torpedo-shaped, or fusiform, animals such as dolphins, barracudas, tunas and open-ocean sharks are built for speed. These creatures live in the water column, not on the sea floor or in the tight quarters of reef communities. Laterally compressed fishes such as triggerfishes, angelfishes and butterflyfishes are built to efficiently slip into and out of the latticework of reef formations, but on the whole they are less capable of generating the speeds attained by more torpedo-shaped animals.

Animals such as rays and angel sharks are flattened from top to bottom. These creatures are well-equipped to maintain low profiles and are typically found along the sea floor in areas where they can go generally unnoticed. These animals often bury themselves in the sand, a great way to go unnoticed by potential predators and prey alike. Armed with this knowledge, you can often discover rays and other sand-dwelling animals by noting the outline of their buried bodies.

Sea snakes and eels have a long, more attenuated shape that is ideal for slinking around in the crevices of reef communities, and that is where you are likely to find them.

By noting and considering the shapes of animals you find in very specific areas, you can begin to acquire valuable insight that will help you put together the marine puzzle. And once you begin to put part of the puzzle together, so many other pieces begin to fall into place, and that is the real payoff in being a good observer. By knowing about behaviors, lifestyle and shape, you begin to anticipate where to find various species. At that point you can pat yourself on the back a time or two, because you will be on your way to becoming a good observer.

Become Aware of Adaptations

To survive, marine animals must adapt — both to their environment and to overcome their limitations. After all, not every species can be the biggest, fiercest, fastest, most superbly camouflaged and most clever. One of the most fascinating aspects of nature and the underwater world is that there seems to be such an endless variety of adaptations that are accomplished in countless ways. Shape, as just discussed, is one of those adaptations. I’d like to point out a few more just for the sake of providing examples, but keep in mind that every animal, or closely related group of animals, possesses some adaptation, or adaptations, that make them unique. Being aware of those adaptations can be the key to enabling you to become a good observer of marine creatures.

Here are some examples. Many brightly colored animals are venomous or repulsive in some way. It’s true of lionfishes, stonefishes and sculpin. These fishes are not among the fastest swimmers. They don’t have to be. Nor are they quick to give ground when approached, because nature has equipped them with other means of defense analogous to the way that snakes and porcupines are created. When on the hunt these animals must be able to strike quickly and overpower their prey. This is equally true for other relatively slow swimmers such as frogfishes and toadfishes.

Using bright color as a warning is not unique to fishes. Many nudibranchs, shell-less mollusks that are closely related to garden slugs, have soft bodies and they are rather slow crawlers. And many species stand out prominently because of their bright colors. These nudibranchs steal the protective stinging cells of corals. Then they place them in the tissue of their own back where those cells serve to repel animals that do not pay heed to the warnings of their bright colors. In this case the colors are intended to say “leave me alone.”

In the case of other invertebrates, you will want to consider the very basic question of whether an invertebrate is permanently attached to the substrate or whether it is mobile.

If an invertebrate is mobile, can it swim like squid and octopods, does it crawl or does it simply go where wind and current take it as is the general case with jellyfishes? Because jellyfishes are at the mercy of the prevailing conditions, their stings can be quite potent. The same is true of anemones and corals. If an animal cannot pursue its prey, it better get it while the getting is possible.

Consider whether an invertebrate has a shell or hard skin. If it has a shell, what does it do when it needs to grow? Does it swap shells, as is the case with hermit crabs, or molt, as is the case with lobsters, crabs and shrimps? Some shelled animals such as snails keep their shells for life, so they need to maintain it. That is the job of their colorful organs known as mantles. Shell-swapping crabs often attach other organisms to their shells so that a host animal is less obvious.

By considering these adaptations and the challenges that each animal faces, you will gain much better insight into how different species live, who eats whom and when, where and how to find various creatures.

Hone Your Fish-watching Skills

Hone Your Fish-watching Skills

Next time you dive, instead of simply looking at a fish, challenge yourself a little by trying to put the fish in context with its surroundings. Consider its shape and other adaptations it possesses as well as what you know about its lifestyle. See if you can determine whether the animal appears to inhabit a relatively small territory or whether it is in transit. If the fish tends to stay close to one area or repeatedly swims over the same patch of reef, look for a nest site or mate. You won’t always find them because they are not always present, but in many instances by applying a little common sense you will discover a nest, mate or perhaps a food source.

As examples, with the damselfish known as the sergeant majors that occur in tropical seas and California’s state marine fish, the garibaldi, you will often discover a male that is manicuring or protecting a nest, or trying to woo a female. It’s great fun to watch a protective damselfish attempt to ward off other egg-stealing fishes and invertebrates such as sea stars, snails and sea urchins.

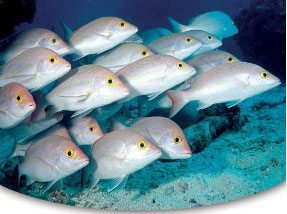

If a fish is a member of a school, try to determine if the fish in the school are feeding. If they are, ask yourself if they are feeding in mid-water or along the sea floor. If they are feeding on the sea floor, as is often the case with tangs and surgeonfishes, look to see if any smaller fishes such as territorial damselfishes are trying to push them out of their territory. On the whole, damselfishes are relatively small, but they seem to have no idea that this is true. They will defend their realm against almost all intruders.

Schooling is a good way for fishes to gain access to a mate, and often in schools of hundreds, or even thousands, of jacks you will see male and female pairs, or you will see spawning activity. Next time you see a school of fish, look to see if perhaps they are feeding or if you can locate a male/female pair.

One of my favorite ways of getting oriented in any tropical reef I have not dived is to look for cleaning stations. Cleaning of some kind can be found on the majority of reef dives, and the cleaning stations are often a great place to find interesting activity that centers on fishes and some other animals. Cleaning stations are often found around prominent outcroppings such as a big coral head or sponge that is on a point. If you find cleaning activity in a given place on one dive, you will often see cleaning there again on subsequent dives.

Of course, you can conduct a similar exercise with any group of animals, but fishes are present almost every time you make a dive, and if you are a good observer, watching them closely will help you learn a great deal about the animal you are watching and about life in the sea.

Learning to be a good observer of marine life is more of an art form than an exact science. Everyone brings a different background to their diving experiences and as a group, we learn to dive in a lot of different places. After learning we travel to different places and experience different phenomena.

When you are new to diving and when diving in an area that is new to you, my suggestion is to first learn about the bigger ecosystem. Getting a grip on the big picture provides you with a frame of reference so you “have a place to put” the smaller pieces of the puzzle. By understanding the big picture you can begin to understand where, when and why you are likely to find the creatures that live in a particular ecosystem. And once you start to understand that information, it will be far easier to understand and anticipate their behaviors.

You’re Watching Them, They’re Watching You

In almost every encounter with fishes, turtles and other big creatures, it has served me well to do whatever I can to make myself appear nonthreatening and unobtrusive. For example, when I first encounter a turtle, instead of trying to get as close as I can as fast as I can, I often avoid eye contact and try to appear interested in something else. In this way I think I appear to be nonthreatening and my behavior often seems to encourage the turtle to acclimate to my presence instead of speeding off into the distance.

When observing marine life, move slowly and be patient. Avoid chasing subjects and barging into territories like the proverbial bull in a china cabinet. As a rule, animals will flee or hide, and even if you get close to the animal, you often fail to get the most out of the opportunity, because you have disrupted the animal’s natural behaviors.

Story and Photos By Marty Snyderman