Some are extraordinarily colorful and equally animated. Others are drab or transparent and hard to see. Some are active cleaners. Others are scavengers. Some have rather large, sophisticated eyes. Others are blind. Many live in association with the seafloor and only swim occasionally, and some live in association with other animals such as anemones and sponges. Others spend their entire lives swimming in the open sea. Some are smaller than your smallest fingernail. Others grow to a length of at least 26 inches (66 cm). Some are quite noisy. Others silent. All are shrimps, and collectively they have a big story to tell as the world’s 2,000-plus species of shrimps play important roles in almost every aquatic ecosystem.

Shrimps occur in a variety of freshwater and marine habitats including lakes, rice paddies, coral reef communities, rocky reef communities of temperate and subtropical seas, caves and in ocean waters as deep as three miles (five km) below the surface. With so many species living in a variety of habitats, it should not be surprising that shrimps are a rather diverse group of animals. Larger species are often called prawns.

While some shrimps serve in vital roles as cleaners that help rid host fishes of external parasites and fungi, bacteria and dead tissue found on the skin, many other species are active scavengers. A number of open-water shrimps feed on tiny animals collectively known as zooplankton and, in turn, they are pursued by myriad fishes. To avoid predators, most open-ocean species migrate daily between the surface where they feed at night and deeper water during the day. Both freshwater and saltwater shrimps are readily preyed upon by many creatures, especially fishes and seabirds.

As divers many of us first encounter shrimps when we see them crawling on the face of or even into the mouth of a grouper or moray eel as the shrimp provides its cleaning services to the host fish. We also see them, or at least we see their bright, highly reflective eyes shining in the distance, at night as they reflect the beams from our dive lights. However, in many instances when light-carrying night divers approach, the shrimps dart away or quickly bury themselves in the substrate. But just when you are about to give up, thinking that you will never get a good look from close range, a cooperative shrimp sits perfectly still showing off its dazzling colors and handsome body.

In other scenarios we see shrimps that seem to be trying to make their presence known. They wave their long, wispy antennae about or suddenly “pop” up and down or otherwise move from place to place in a sporadic, attention-getting fashion. In still other instances we hear the popping and crackling sounds they make as they turn Jacques Cousteau’s so-called “silent world” into a kingdom that is anything but silent. If you miss the sounds when you are underwater, you often hear them echoing off the hull of your boat as you lay your head on your pillow at the end of a diving day.

A Malaysian crinoid shrimp blends in with its host crinoid. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Phylum Arthropoda, Class Crustacea

As is the case with more than 75 percent of the world’s animal species, shrimps are described in the phylum Arthropoda. They are members of the class Crustacea. In addition to true shrimps, a list of crustaceans includes lobsters, crabs, barnacles, copepods, isopods, amphipods and stomatopods.

Like all crustaceans, shrimps display bilateral symmetry, and have jointed appendages and a hard exoskeleton. Many possess large claws that are used in defense and for capturing and gathering food. Living inside of a hard shell has its protective advantages, but the lifestyle is also fraught with problems. Growth is difficult and can be dangerous as shrimps and other crustaceans must crawl out of their restrictive shells to grow.

Shrimps have elongated bodies that are typically divided into two major sections. One section is made up of the head and thorax, which are fused together forming the cephalothorax, a body part also known as the carapace. The second body section is a segmented abdomen.

The abdomen and tail are proportionally longer than those of lobsters and crabs. Shrimps depend upon their tail and abdomen when swimming. By rapidly flexing their abdomen and tail muscles, shrimps can propel themselves backward at surprisingly fast speeds, and almost all species rely upon their swimming ability to escape predation. The underside of a shrimp’s tail is lined with several broad, well-developed appendages that enable most species to swim slowly forward while maintaining fine maneuvering capabilities and body control.

Shrimps are equipped with a number of specialized legs. Eight pairs of legs are positioned on the thorax. The three most forward pairs are used for feeding, while the other five pairs are used in clinging and walking. The abdomen is lined with five pairs of relatively short, rounded legs called pleopods or swimmerets. These legs are used for swimming and burrowing, and some adult females use them to carry their eggs.

Shrimps rely heavily upon their well-developed senses of touch, taste and sight to maneuver around the potential hazards they come across during their lives. One of the most noticeable characteristics of shrimps is their elongated, wispy antennae that are used to both feel and taste their surroundings. Most shrimps are extremely quick to dart away when they detect danger, and the length of their antennae provides the body and vital organs with a margin of safety when danger is detected. In some instances, the antennae are torn free by a predator, but the shrimp’s body gets saved. The eyes of shrimps are on movable stalks, another feature that helps them remain aware of their surroundings.

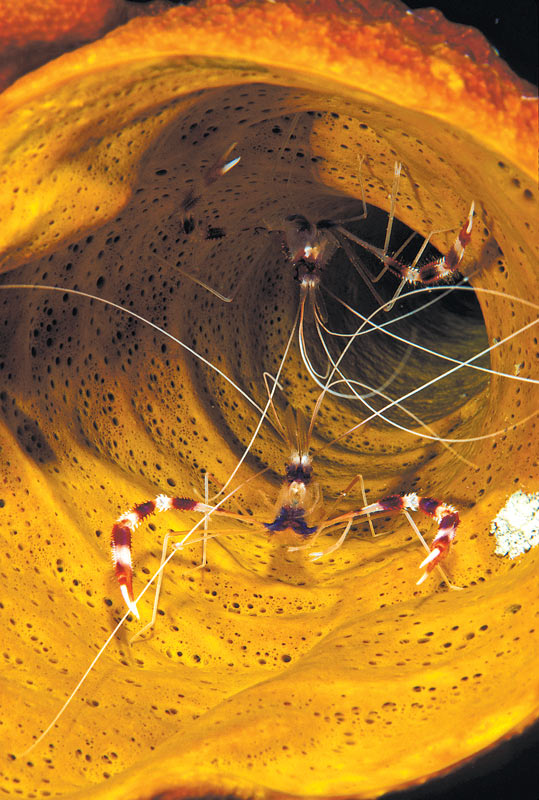

Typically 2-4 inches long, the banded coral shrimp is characterized by alternating red and white body bands, two large, white claws and long, white antennae. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Prominent Shrimp Species

Among the more prominent species of shrimps in many tropical destinations is one known as both the banded coral shrimp and the barberpole shrimp. As both names suggest, this species, Stenopus hispidus, is characterized by alternating red and white body bands. Typically 2-4 inches (5-10 cm) long, they are also characterized by two large, white claws and their long, white antennae. Typically hiding by day, they usually emerge at night to roam the reef in pursuit of food.

The banded coral shrimp is a cleaner species as are the commonly seen Caribbean species known as Pederson’s cleaning shrimp, a delicate creature characterized by its semitranslucent body and blue-to-purple front legs, and the bright red, yellow and white scarlet lady cleaning shrimp (Lysmata grabhami). In Indo-Pacific waters many shrimps serve as cleaners, one of the more commonly seen cleaners being the scarlet skunk shrimp (Lysmata amboinensis). In Southern California the red rock shrimp (Lysmata californica) is the most commonly encountered cleaner shrimp.

Other prominent Caribbean species include the colorful anemone shrimp (Periclimenes yucatanicus), the orange and white, half-inch- (1.25-cm-) long Thor anemone shrimp (Thor ambionensis) and the Yucatan anemone shrimp (Periclimenes yucatanicus). As their names suggest, these species are usually seen in association with an anemone. Another Caribbean diver pleaser is the red night shrimp (Rhynchocinetes ringens), a nocturnal species that has bulbous eyes and a bright red body.

Blind Shrimps

In many parts of the Indo-Pacific a number of species of blind shrimps share their burrows with a variety of fishes known as partner gobies. In each burrow at least one shrimp excavates and maintains the burrow as the goby keeps a vigilant eye out for potential threats. The shrimp literally keeps in touch with the goby, placing at least one of its antennae on the fish’s body.

If the goby senses danger, the fish quickly retreats into the burrow. The blind shrimp follows in the blink of an eye. With many species of shrimps and gobies that are known to participate in this relationship, adults of both species are only seen with the other species.

In many parts of the Indo-Pacific a number of species of blind shrimps share their burrows with a variety of fishes known as partner gobies. In each burrow at least one shrimp excavates and maintains the burrow as the goby keeps a vigilant eye out for potential threats. Photo by Marty Snyderman.

Pistol Species

A number of species are collectively known as pistol shrimps (aka snapping shrimps and popping shrimps). Occurring in a variety of habitats, these shrimps are given their common name due to the loud sounds they make that bear some resemblance to the sound of a fired pistol. Pistol shrimps possess a pair of pincers, with the larger one being used to produce a snapping sound that can be loud enough to startle an unsuspecting diver.

Specialists believe that these shrimp use the sound to warn other members of their species to steer clear of a snapper’s territory and to stun prey that usually consists of a variety of very small fishes.

Mantis Shrimps

While all shrimps are crustaceans, not all shrimps are described in the same order. The approximately 400 species known as mantis shrimps make up the order Stomatopoda. Most shrimps we encounter are described in the order Decapoda. Possessing 10 walking legs, decapods are sometimes called “true shrimps.”

The common name mantis shrimp is derived from the fact that these crustaceans bear some structural resemblance to the terrestrial insect known as the praying mantis. While some species of mantis shrimps appear in hues of pedestrian browns, many others species display brilliant colors.

Mantis shrimp are equipped with astonishingly powerful, somewhat oversized claws that look like a folded-up jackknife.

According to the way their claws are used, stomatopods are often separated into two groups. The claws of the mantis shrimps known as “spearers” are lined with spiny projections topped with barbed tips. Claws with this design are used to stab and grab prey. These species tend to prefer fishes and other soft-bodied prey. Spearers are also armed with a calcified club on the “elbow” of the claw where the claw folds. The elbow club of those species known as “smashers” is much more developed, while their “spear’ is less well-developed. Smashers routinely feed upon snails, crabs, oysters and other hard-shelled animals, and their clubs are used to bludgeon and smash their prey.

Members of both groups strike with in-the-blink-of-an-eye quickness. The power and smashing ability of the claws has often been compared to a bullet shot from a .22-caliber rifle, and in addition to smashing the shells of crabs and mollusks, many mantis shrimps have broken the double-paned glass in an aquarium with a single strike as well as severing the fingers of fishermen who have unwittingly tried to remove an unhappy shrimp from a net.

A Costly Cocktail?

While divers and underwater photographers appreciate shrimps for their beauty and behaviors, when most people think of shrimps they think of food. Humans consume large quantities of shrimp. The meat is high in protein and low in fat, a good combination where nutrition is concerned.

The annual take of commercial shrimp fisheries worldwide is almost 3 million tons. In the United States alone the catch is about 125,000 tons. Most of the shrimp that is harvested in the United States is caught along the country’s southeastern coast and in the Gulf of Mexico.

Both in the United States and among the international community, shrimp fishing and shrimp fishing methods are highly controversial. Trawling with large nets that are raked over the bottom can help fishermen catch a lot of shrimp, but the waste from bycatch (unwanted species) can be horrific, making shrimp fishing among the world’s most wasteful fisheries. Overharvesting of shrimp and extremely high bycatch kills have led to serious problems with fisheries.

There is hope that the elimination of wasteful practices and the rise of shrimp farming will reduce the pressure on shrimp. However, enforcement is difficult and shrimp farming is not without its environmental concerns.

The Lifecycle of Shrimps

While the sexes are separate in some species, in others the shrimp begins its life as a male. After one mating period, however, the animal undergoes a transformation and becomes a female. When reproducing, male shrimps deposit their sperm into a gelatinous mass located between the fourth pair of walking legs of the female. Once the female has accepted the sperm, she lays her eggs in batches of as many as 15,000. The females usually care for the eggs by holding them in a brood chamber on the underside of their tail. However, in some species the fertilized eggs are scattered into the water, with the young being left to develop on their own.

The eggs hatch and soon become drifting larvae. The larvae change shape and form as they grow, developing into adults after molting their skin several times. Various species require between 30 and 160 days to develop into sexually mature animals. In some species the adults die shortly after breeding, but other shrimps live for as long as seven years.