Want to get away from it all? Enjoy a little peace and tranquility? No ringing telephones, doorbells, ranting bosses, radios or stereos turned up so loud you vibrate, and no screaming kids. No one calling in the middle of dinner to tell you what to think, who to vote for or what to buy. Just peace, quiet and nature. This was the message conveyed by the learn-to-dive ads when I was a kid some 40 years ago. Back then the underwater realm was routinely referred to as the silent world.

But during the next four decades underwater explorers learned that the so-called silent world is anything but silent. Instead, it is a cacophony of noises with a variety of creatures chiming in. Dive enough places and you are likely to hear sounds of snapping, crunching, thumping, grunting, clicks, whistles, songs and more with the sounds emanating from animals that vary in size from shrimps to whales. Crashing waves, rain, hot lava flowing into the sea, diving birds and a number of other phenomena also contribute to the myriad sounds of the underwater world.

Crunch. Scrape. Grind. Crunch, crunch. Silence. Crunch. Grind. Divers who are exploring coral reef communities often hear a sound pattern like this with repeated crunching and scraping noises separated by brief periods of silence. At first, many divers suspect that a boat anchor is dragging, but they soon discover the noise is being created by one or more parrotfish chewing on a coral head as the fish crunches and scrapes chunks of coral to get to food sources of algae that live inside the coral.

The crunching and scraping of parrotfishes are not the only sounds emanating from the world of fishes. Not by a long shot! In fact, an estimated 300-500 species of fishes make some kind of sound, although many of the sounds are of such low frequency that the unaided human ear cannot detect them. Among other reasons, these sounds are used to deter predators, warn other members of their species of impending danger, and attract mates.

The three main ways fishes produce sound are by rubbing body parts together in an act known as stridulating; vibrating or otherwise using muscles on or near their swim bladder, or drumming; and via hydrodynamics, meaning by quickly changing speed and direction.

Sounds of Stridulation

Stridulation occurs when a fish rubs together body parts to produce sound, with various body parts being used by different species. The sea catfish (Galeichthys felis) use spines on its pectoral fins to create a squeaking sound. Other fishes such as the pipefish (Syngnathus louisanae) and the northern seahorse (Hippocampus hudsonius) produce sounds by rubbing together skeletal bones. Fishes also produce sound by rubbing or grinding their teeth, especially while feeding. These are just a few examples that illustrate various ways that fishes produce sound via stridulation, but hundreds of other species produce sounds in a variety of other ways.

Good Vibrations

Many fishes create sound by contracting muscles around their gas-filled swim bladders, an internal organ that functions both in buoyancy control and as a kind of echo chamber in sonic communication. The oyster toadfish contracts muscles around its swim bladder at a phenomenal 200 times per second, causing the bladder to rapidly expand and contract. This Herculean effort is sustained by the fastest-twitching muscles yet discovered in any vertebrate animal, and it creates a sound that is more like that of a whistle than a drum.

Even though there are only an estimated 100 species of squirrelfishes and soldierfishes, they are among the most conspicuous of all fishes in many coral reef systems around the world because of their bright red color and tendency to hang almost motionless under ledges and in the openings of recesses and crevices where they are easy to spot during the day. When approached, squirrelfishes and soldierfishes often produce loud grunting sounds by vibrating their swim bladders. These sounds are surmised to be an effort to ward off predators and warn other members of their species of imminent danger. It is also believed that these species use similarly produced sounds to claim territory.

In damselfishes such as the sergeant majors that occur in tropical and semitropical seas and the garibaldi, California’s state marine fish, males attract females by swimming above the nest the he-fish build in a “strut my stuff” figure-eightlike pattern. The male also makes low-frequency sounds by vibrating his swim bladder, a sound that can definitely be heard by divers who listen closely. The bigger the male, the lower frequency vibrations he creates, the better his chances of getting his girl!

Damselfishes are also known to make noises to ward off predators.

These fishes commonly known as grunts make — no surprise here — grunting sounds when cornered or caught. They do so by grinding teeth called pharyngeal teeth that are found near the back part of the throat where the gill slits open, and then amplifying that noise by using their swim bladder as a resonator.

RELATED READ: THE UNDERWATER SCIENCE OF SOUND

Hydrodynamic Sound

Hydrodynamic sound production in fishes results when an animal quickly changes velocity and/or direction. Hydrodynamic sounds are low-frequency and are not usually used in intraspecies communication. The sounds produced from a swimming fish are the result of the shape of the fish and the properties of water. As an object moves through water, the water around the object is compressed and moved, thus, creating sound.

Finger-sized shrimps with an oversized claw that bears some resemblance to a boxing glove is an accurate description of another group of underwater noisemakers that inhabit shallow seas around the world. The crustaceans commonly known as snapping shrimps use their big claws to produce sharp, popping sounds similar to that of the cracking of a whip. These sounds are used to deter predators, stun prey and to communicate with other members of their species.

You might have heard the sounds of snapping shrimps when trying to sleep on a boat that was anchored in a shallow sea or when visiting a beach and sticking your head underwater. If you heard something that sounds like you put your ear next to a fresh bowl of Rice Krispies in just-poured milk, then snapping shrimps have probably serenaded you.

When snapping shrimps snap, they open their large claw and then quickly slam it closed. However, for at least one tropical species, Alpheus heterochaelis, the amazing sound is not produced from the clap created when the parts of the large claw come together as it is for other snapping shrimps, but instead from a bubble that is created by the rapid closing of the claw.

Studies have demonstrated that when the claw of this species snaps closed a stream of water is forced out of a socket in the claw at a speed of up to 62 mph (100 kph). This action produces a pressure bubble in its wake. At first the water in the bubble loses pressure, then gains pressure. That loss and gain in pressure causes an air bubble to form, grow and collapse with a very loud bang in a process that occurs within 300 microseconds. The noise is so loud that military specialists tell us that submarines can “hide behind” the noise while on the move.

Shrimps are not the only crustacean noisemakers. Spiny lobsters (not clawed like the Maine lobster) often make a squeaky, rasping sound to deter predators or to warn them that the lobster is about to whack them with their spiked antennae. The sounds are produced when the lobster wiggles its antennae, causing projections at the base to skid across ridges on the animal’s head in a manner that is somewhat like that of a violin being played.

Using Sound to Communicate

Communicating through sound is very important in the lives of dolphins and whales. These animals routinely move over great distances, and being highly social creatures they need to stay in contact with each other in the limited visibility of the underwater world. Sound waves travel almost five times faster underwater than in air, thus sound can be quite an effective means of communicating over distances. Whales create sounds produced by the movement and release of air through their blowhole, or blowholes, and by the movement of air through the body, not by vocal cords or beaks.

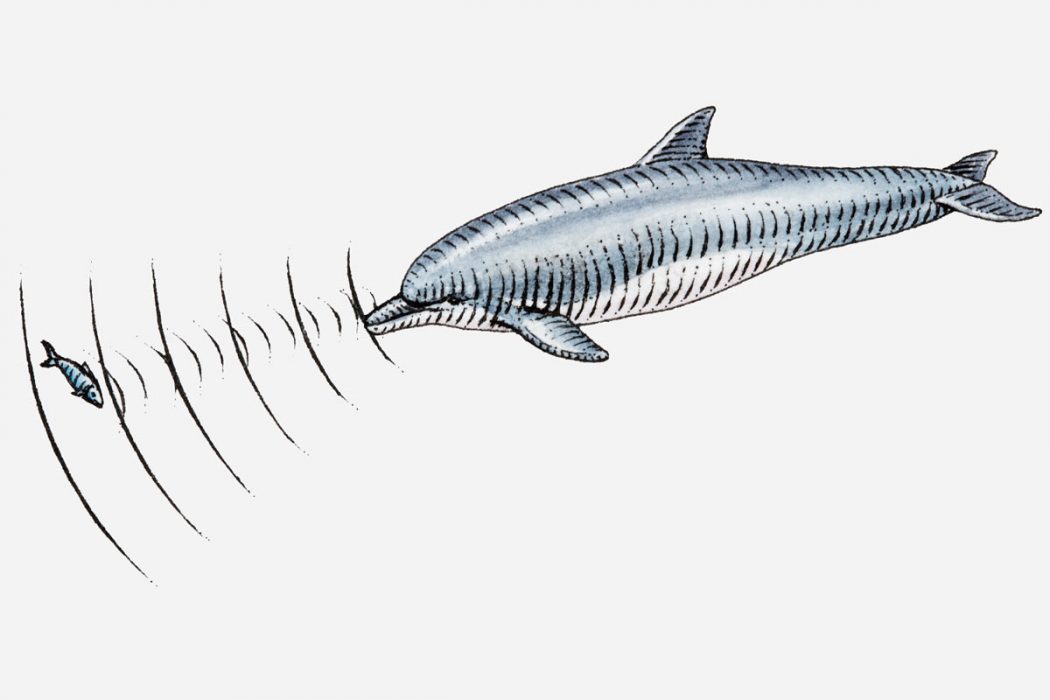

Toothed whales, a group that includes dolphins, use sound not only to communicate, but also to “see” as they use sound waves in a form of natural radar. These mammals emit a series of high-pitched whistling sounds and rattlelike clicks. The whistles are unique to each individual, much like our own voices, and are called “signature whistles” because they allow other animals in a pod to identify the whistler. When diving near a pod of dolphins you will often hear a single whistle followed by a similar-sounding whistle from another nearby animal, as the two animals use their whistles to “shake hands.”

RELATED READ: ALL ABOUT WHALES, DOLPHINS AND PORPOISES

The click waves emitted by toothed whales strike objects in the water and bounce back to the sender, being received by a fatty organ called a melon that is in the sender’s head. The sound waves are then analyzed, and it is well documented that toothed whales can determine the speed and direction of moving objects and whether an object might be prey or potential danger. In addition, the emitted clicks are sometimes used to stun prey, especially small fishes, when toothed whales hunt.

Humpback whales are often called the singing whales, and their songs have been well studied in recent years. It is believed that only mature males sing, and that they do so to attract a mate. When singing, all of the whales position themselves near the surface with their bodies facing at a downward angle. Interestingly, the songs change over time, and it has long been known that all whales in a given area sing the same song and with each new year a slightly different version emerges at the top of the whale’s hit list.

In the world of whales and dolphins it is also believed that sounds produced by slapping their tails (tail lobbing) and pectoral fins against the surface of the sea as well as the sound produced when the whales crash and splash into the sea as they breach are also part of their communication with one another. Males are thought to use the sounds from breaches to help establish dominance.

These days I’d have to say that it is clear that the underwater world is a cacophony of natural sounds, and anything but the silent kingdom it was said to be only a few generations ago.