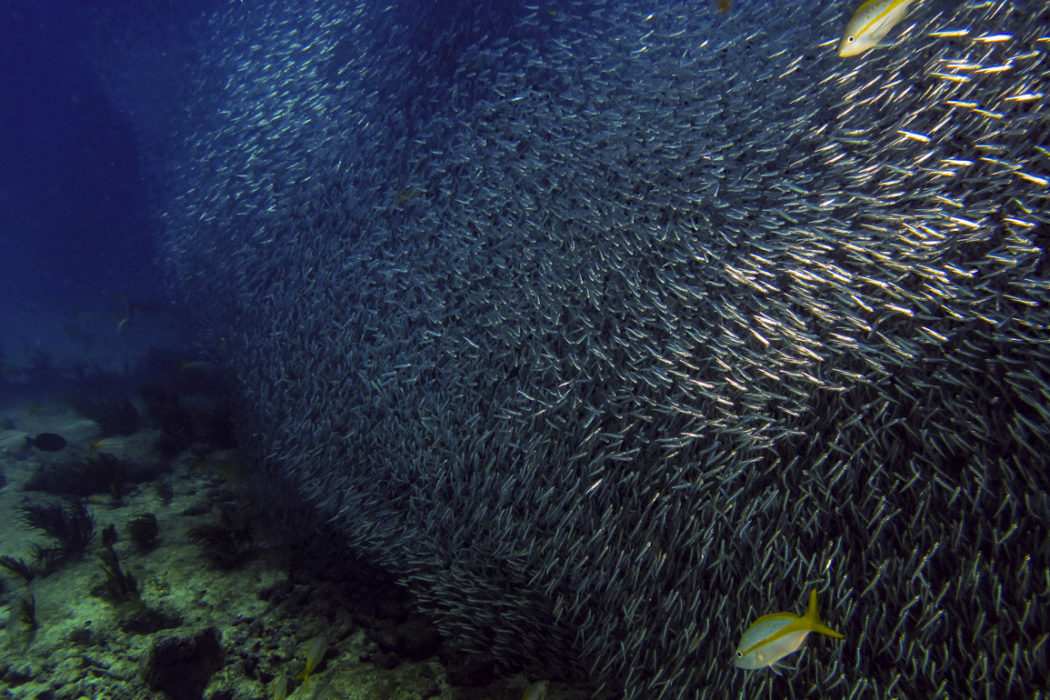

Where in the continental United States can you explore vibrant coral reefs and hundreds of years of historical artifacts while diving in warm, subtropical waters, all in a location so special it has been designated an underwater treasure by Congress? Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Within the boundaries of the sanctuary lie spectacular, unique and nationally significant marine resources, including the world’s third-largest barrier reef, extensive seagrass beds, mangrove-fringed islands and more than 6,000 species of marine life from barracuda to butterflyfish, sea turtles to sea anemones, and lobsters to lobed star coral.

The Florida Keys are a chain of islands that extend from the southern tip of the Florida mainland southwest to the Dry Tortugas, a distance of around 220 miles (352 km). Like much of the rest of Florida, the foundation of the Keys is limestone rock. The term “key” comes from the Spanish word “cayo,” meaning “little island” — and any drive down U.S. Highway 1 or glance at a map quickly reveals that the Florida Keys are a string of exactly that. The Keys are actually made up of ancient coral reefs (Upper Keys) and sand bars (Lower Keys) that existed when the sea level was much higher during the Pleistocene Epoch, 125,000 years ago. During the last ice age (100,000 years ago) sea level dropped, exposing the coral reefs and sand bars, which over time became the fossil and rock that makes up the island chain today. As glaciers and polar ice caps started melting 15,000 years ago, the land flooded, shaping the Keys we know today.

Photo courtesy of NOAA/National Marine Sanctuaries.

Conservation History

Although today the island chain is acclaimed for fabulous fishing and diving, the Keys have a long history of recognizing and taking steps to protect those resources. At the turn of the century, for instance, when the nation’s love affair with stylish hats began to endanger wading birds prized for their decorative plumage, President Teddy Roosevelt designated the Key West National Wildlife Refuge to protect native birds in 1908 — just five years after the national wildlife refuge system was established.

The idea to protect underwater spaces from rampant exploitation lagged about a half-century behind. The first underwater park in the region — and, indeed, the first in the world — was John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, designated in 1960 by the state of Florida. Activists in Miami, led by the journalist who became the park’s namesake, lobbied to have it set aside to protect the coral reefs. It took 15 years before the Keys had their first national “underwater park” in the form of the 103-square-nautical-mile (350 sq km) Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary, which stretched from Carysfort Reef to Molasses Reef in the Upper Keys. In 1981, an additional five square nautical miles (19 sq km) of the Lower Keys were set aside as Looe Key National Marine Sanctuary, as a means to conserve another reef that was popular with divers.

Throughout the 1980s, scientists had documented decreases in living coral cover on the reefs, major seagrass die-offs, and declines in fish populations. Incidents of coral bleaching and diseases had been on the rise, and iconic species such as the long-spined sea urchin (Diadema antillarum) and the queen conch (Strombus gigas) — the adopted mascot of Key West — were experiencing widespread die-offs. Reports of deteriorating water quality also were coming in.

Popular support for increased marine conservation was further galvanized when three large ships ran aground over 18 days in 1989, damaging sections of the reef tract. The Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 was fresh in the national consciousness, and there were proposals to drill for oil in the region. Together, these events caused concerns about the long-term fate of the Keys’ fabulous marine life to tip in favor of action.

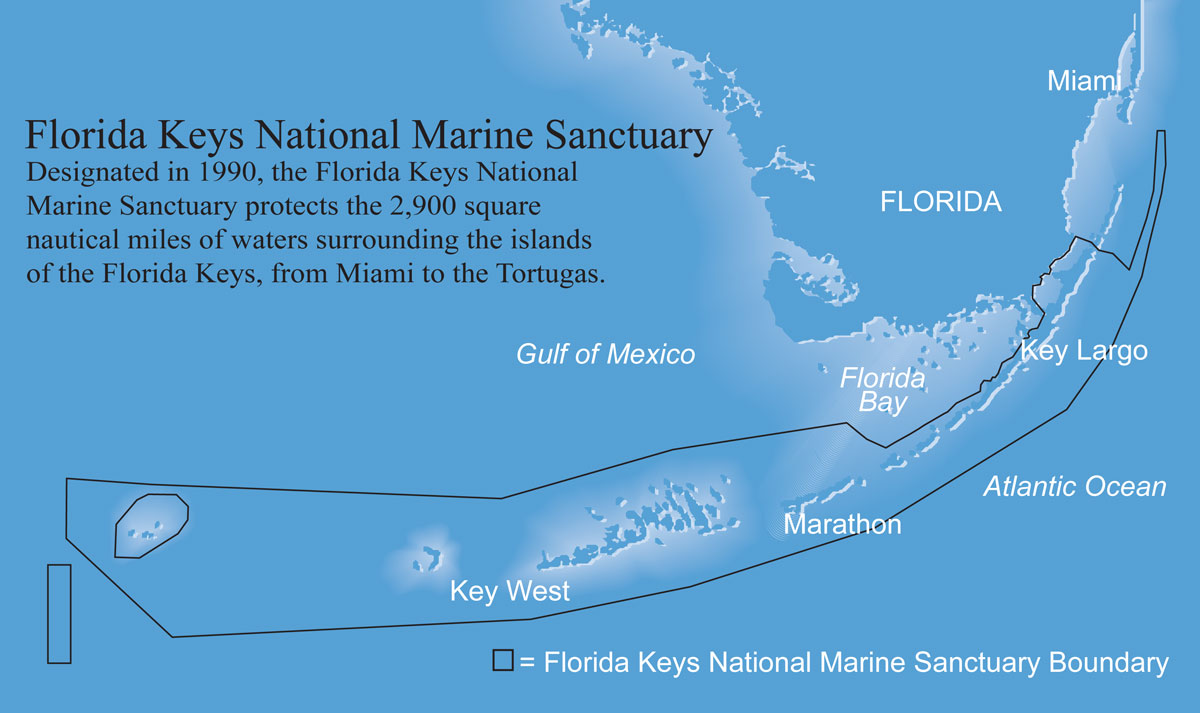

On November 16, 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed into law the bill establishing Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, incorporating the pre-existing Key Largo and Looe Key sanctuaries. Today, the sanctuary encompasses 2,900 square nautical miles (9,860 sq km) of the Keys’ waters as part of a larger complex of public places that protect both land and sea, including four national wildlife refuges, nine state parks and three state aquatic preserves. About 60 percent of sanctuary waters are in state waters, but the sanctuary as a whole is cooperatively managed by federal, state and local agencies, working together on education, outreach, science, monitoring and enforcement.

About 3 million visitors flock to the Keys each year, of which roughly 700,000 dive or snorkel in the waters of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. An additional 72,000 people are year-round residents, many of whom enjoy watersports such as boating, fishing, kayaking, Jet-Skiing, paddleboarding, or simply swimming and snorkeling in near-shore waters. Most of the dive spots of the Keys are accessible only by boat, but patch reefs can be reached within two to three miles (3.2 to 4.8 km) of shore and rental boats are available at local marinas. About 80 dive operators serve the area, generally offering morning and afternoon two-tank trips. Most popular dive sites are found along the reefs and wrecks on the Atlantic side, but the backcountry waters of the Gulf side are also very popular for outdoor activities, such as fishing, paddleboarding and kayaking.

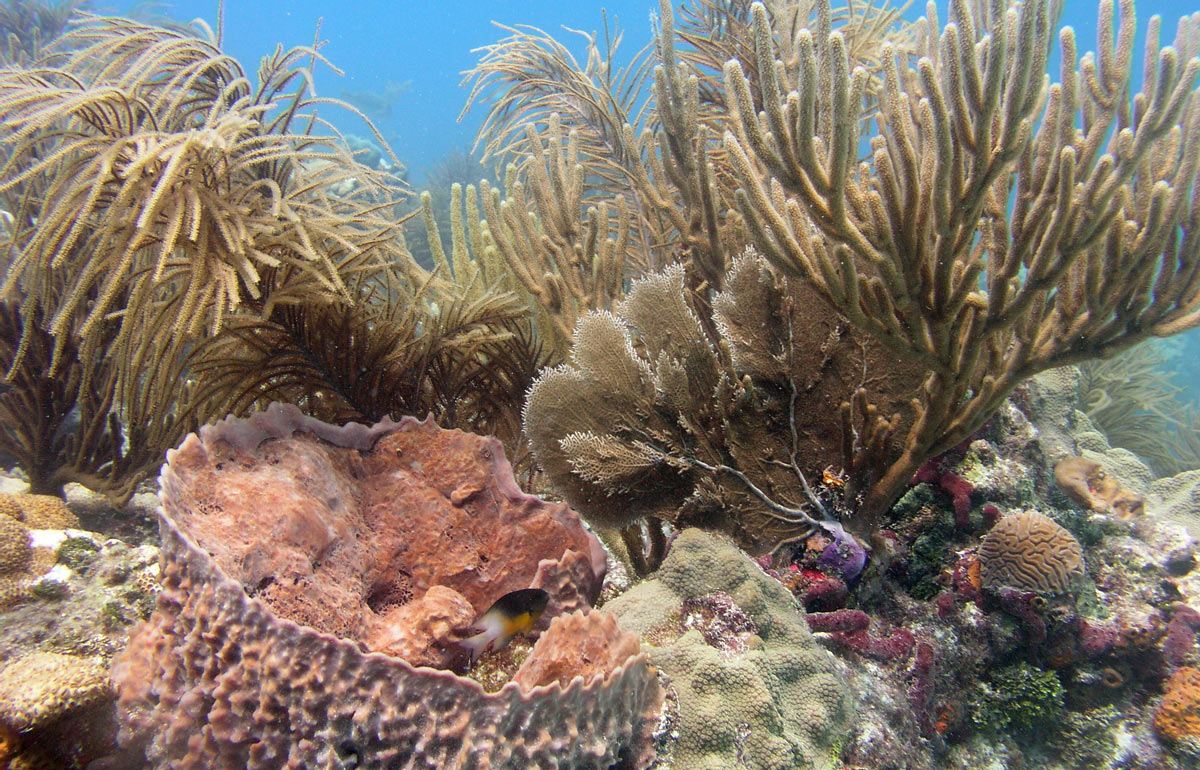

The reefs of the Florida Keys are biodiverse, with a variety of hard and soft corals, sponges and other marine life. Photo courtesy of NOAA/National Marine Sanctuaries.

The Reef Structure

One of the premier diving attractions of the Keys is the Florida reef tract — the third-largest barrier reef in the world — which originates south and west of Cape Florida around Fowey Rocks and stretches more than 220 miles (352 km) to a remote set of islands known as the Dry Tortugas. Reef formations of three main types (hardbottom, patch reefs and bank reefs) run parallel to the string of islands, picking up just east of a gently sloping shelf that forms Hawk’s Channel. The only major break is between the Marquesas Keys and the Dry Tortugas.

The most common, but often overlooked, coral habitat is the hardbottom community. Found close to shore, the low cover of hard corals, sponges and octocorals provides a refuge for fish as they transition from living in the mangroves to the outer reefs. Patch reefs are aptly named, as they are part of a larger patchwork of large seagrass beds and bare sand. The coral composition here differs from that found on the outer bank reefs, with sea fans and whips being more common. Massive mountain star corals, brain corals and pillar corals are found in fairly shallow water, growing to within inches of the surface. Yellowtail snapper, at home during the day on the patch reef, voyage out at night to feed on invertebrates such as shrimp and tiny crustaceans hidden in the surrounding seagrass beds. One can often find a cleaning station at a patch reef and spend time watching the grouper or barracuda being serviced by neon gobies. These seagrasses are also an important food source for large, iconic vegetarians such as manatees and green sea turtles. As one heads farther out to sea, shallow-water habitat is dominated by turtle grass and manatee grass, with scattered coral heads and small patch reefs.

Further out to sea, the most popular reef habitat for diving is the spur-and-groove bank reefs. These are the most developed reefs, both in the variety of corals and the dominance of reef-building species such as the threatened elkhorn and staghorn corals. Many of these reefs are found deep below the surface, and have the most stable temperature and salinity because of the proximity of the Florida Current. The well-known Carysfort Reef, Molasses Reef and Sombrero Reef are examples of bank reefs.

Once at the bank reef, depending on conditions and ability, there are different zones that can be explored. Extremely shallow and perfect for snorkeling, the reef flat or back zone is ripe with juvenile tropical fish darting in and out of crevices of staghorn coral. In higher winds and rougher seas this area can resemble a washing machine as waves break over the reef. The majority of diving in the Keys occurs on the fore reef with the classic spur and groove formations. The Keys are known for their fish diversity and abundance, and diver fish counts often tally many species in a single dive. Due to the shallow depths of 15-50 feet (4.5 to 15 m), a diver can easily navigate two or three spurs and grooves before needing to make their way back to the boat. Exploring the sides of the spurs will often reward the diver with arrow crabs or banded coral shrimp, and if one has patience, the yellow-headed jawfish can be spotted in the sand grooves.

Corals tend to form zones according to their depth, which makes for interesting diving. The structural complexity of the coral reef tract provides a haven for fish, crustaceans, mollusks, worms and sea urchins. More than 40 species of stony corals and 500 fish are found here. On one reef alone off Looe Key, a survey found 63 types of stony corals, 42 species of octocorals and two species of fire coral.

A large expanse of elkhorn coral grows at Horseshoe Reef, a shallow reef off Key Largo. Elkhorn coral is an icon of the Florida Keys but was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2006. Photo courtesy of NOAA/National Marine Sanctuaries.

Wrecker’s Delight

Centuries ago, the Keys’ coastline had a different cultural significance. Treacherous for mariners, strategic for military forces and critical for shipping, the proximity of its shallow waters to the Florida straits was a recipe for shipwrecks. Starting with the Spanish explorers, fleets navigated these straits to reach the Gulf of Mexico or get a head start on their journey back to Europe, often veering dangerously — sometimes fatally — close to shallow reefs as they worked their way to the nearby Gulf Stream.

Today, the Keys’ perilous past translates into a hotspot of wreck diving that spans centuries of history. An estimated 2,000 shipwrecks have occurred in the Florida Keys since the European exploration of the Americas began, and one goal of the sanctuary is to preserve this maritime heritage. To make it easier for visitors to experience this undersea history, the sanctuary created a “shipwreck trail” featuring nine historic ships spanning several centuries. On the sanctuary’s website, visitors can view site maps and read about the history of each of these ships. Sites are available on the shipwreck trail for divers of any experience level, from shallow sites accessible to adventurous snorkelers to deeper dives of l00 feet (30 m) or more where swift currents may be encountered.

The oldest ship on the trail is the San Pedro, a member of the 1733 Spanish treasure fleet that sank in 18 feet (5.5 m) of water after being caught in a hurricane a mile (1.6 km) south of Indian Key. The site is composed of replica cement cannons along with a distinct pile of ballast stones that originate from European river beds and red ladrillo bricks from the ship’s galley. The trail includes remains of wood hulls from two 19th-century shipwrecks. The first is believed to be the North America, which was lost in 1842 while bound for Mobile, Alabama, carrying furniture and dry goods from New York. The second is the Adelaide Baker, a double-hulled 153-foot (46 m) ship, sheathed with copper, which was bound for Savannah, Georgia, with a load of timber when it sank in 1889. Early 20th-century wrecks with steel hulls include the City of Washington, sunk in 1917, and the Benwood, lost in 1942. The remaining three ships — the Duane, Eagle and Thunderbolt — were intentionally sunk in the 1980s to provide artificial habitat.

Even after the sanctuary was designated, projects to scuttle 20th-century ships have been approved on a case-by-case basis. Recent projects include the Spiegel Grove, scuttled in 2002, and the USS Vandenberg, sunk in 2009. Both were projects developed by local groups to enhance tourism in the area and provide novel diving opportunities in deeper waters. These sites are among the Keys’ most popular.

In the Zone

The concept behind the national marine sanctuary system, created in 1972 by Congress, is to conserve, protect and enhance the biodiversity, cultural legacy and ecological integrity of special underwater places. National marine sanctuaries support use of the nation’s underwater treasures, to the extent that the integrity of the resources they protect can be maintained for future generations. Marine zoning is a cornerstone of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary’s management plan to preserve resources and minimize potential conflicts among ocean users.

Five types of marine zones offer varying levels of protection, designed to enable a balance between protection and sustainable use. Most of the sanctuary is open to diving and snorkeling, but visitors should always check maps and regulations before planning a trip.

Sanctuary preservation areas and Western Sambo Ecological Reserve are popular destinations for divers because they are closed to fishing and contain reef habitat. These sites teem with fish such as barracuda, moray eels, goliath grouper, parrotfish, angelfish and stingrays. Diving, snorkeling and boating are allowed without a permit, but removing any marine life in these areas is prohibited. The former Key Largo and Looe Key sanctuaries, now classified as “existing management areas,” also remain popular dive sites. Hook-and-line fishing, along with diving for lobster and crab, is still allowed in these areas, but divers cannot spearfish or take tropical marine life.

If you venture 70 miles (112 km) west of Key West to the Tortugas region, make sure you plan ahead if you plan to dive in the Tortugas Ecological Reserve North since a permit to tie to a buoy and dive will be required and the Tortugas Ecological Reserve South is a “no entry zone.” The ecological reserve is designed to protect natural spawning and nursery areas needed to sustain populations of fish and other marine life by setting aside large, contiguous, diverse habitats. All entry is also restricted at the four “Special-Use Zones Research Only” areas at Tennessee Reef, Conch Reef, Looe Key patch, and Eastern Sambo, where permits are required to enter.

Charting a New Course

Despite notable successes, such as improvements in water quality and increases in fish populations that have been tied to the creation of no-take zones, a 2011 condition report of the sanctuary found its coral habitats have been declining since the late 1970s. Many of the factors in these declines, such as coral diseases, bleaching events and storm damage are national, international or mother nature-generated and hard for the sanctuary to manage directly. To address ongoing issues, the sanctuary is also in the midst of an extensive, multiyear review of its zones and regulations, looking for ways to locally address factors that can be influenced.

A more recent pressure on the coral reef ecosystem is the spread of invasive lionfish. With no known predators, a voracious appetite and the ability to rapidly multiply, the lionfish (native to the Indo-Pacific) has become a common site on Keys reefs. To reduce these stressors, the sanctuary relies on creative public-private partnerships. Their partnership with the Key Largo nonprofit Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) has been important for raising awareness of the threat posed by a growing population of invasive lionfish in local waters. REEF organizes competitive lionfish derbies, in which teams compete for honors while trying to bag the largest number — and largest-sized — lionfish in a one-day fishing derby. Reducing the number of lionfish on local reefs eliminates pressure on native fish species that they prey on.

Sanctuary staffer Hank Becker installs a mooring buoy anchor in a sandy patch near coral reef. Photo courtesy of NOAA/National Marine Sanctuaries.

An Ounce of Prevention

Sometimes, the high volume of underwater visitors to the Florida Keys can be detrimental to the reefs — especially if they aren’t familiar with responsible diving and conservation practices. That’s why the sanctuary created an innovative partnership called “Blue Star,” which works with charter dive and snorkel operators to educate their customers about reef-friendly diving before they hit the water. By providing a certification that local businesses can proudly advertise to their customers, Blue Star allows the sanctuary to support sustainable practices by recognizing operators that have taken extra steps to integrate conservation principles into their daily practices.

To earn the certification, each company’s staff is trained on the basics of coral reefs and the threats they face, so they understand the importance of reef etiquette. This knowledge is then passed on to customers through a predive briefing to impress upon them the importance of avoiding contact with corals by securing their equipment, maintaining their buoyancy and refraining from touching marine life. Continuing education and supporting local conservation projects such as marine debris cleanups further extends the influence of the program. Blue Star operators must renew their certification on an annual basis. In return, the Blue Star certification provides operators and the sanctuary with a way to market their environmental practices with customers. Do your part as an environmentally aware diver and look for the Blue Star logo or ask the shop if they are Blue Star-certified before booking your next dive trip.

Another way the sanctuary has worked to minimize the impacts of recreational uses is by developing a system of mooring buoys. Used in marine protected areas around the world, the concept was pioneered in the Florida Keys by two of the sanctuary’s former employees. The sanctuary’s buoys are white with a blue stripe, 18 inches (46 cm) in diameter, and provide a pickup line that boaters can tie off to as an alternative to anchoring on the seafloor. Anchoring in coral or other living rock in less than 40 feet (12 m) or when the seafloor is visible is already illegal, but the mooring buoy system prevents unintentional damage from anchors during low visibility or bad weather. About 500 mooring buoys are maintained by sanctuary staff, often around the shallowest reef areas and on the ocean side of the reef.

Boater education and outreach programs are also a critical component of the sanctuary’s management strategy. The sanctuary’s first challenge has been simply raising awareness about the fact that the Keys’ waters are designated as a protected area. Although there is only one inbound roadway to the chain of islands, there is no single point of entry to the reef — visitors from around the world arrive in the sanctuary by land, sea or air, some by private or chartered boats or planes.

One of the most important goals of the sanctuary’s Team OCEAN volunteer program is to prevent boat groundings, which can inflict damage on seagrass beds and corals that lasts for decades, if unmitigated or unrestored. Even with modern channel markers and navigational systems, groundings are a constant concern in a place where many boaters come from elsewhere and are unfamiliar with local waters.

Topside Visit to Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center

If divers are weathered out or just want a break while in the Key West area, they can learn more about the Florida Keys at the sanctuary’s visitor center in Key West. Enter the Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center and take a journey into the world of the native plants and animals of the Keys, both on land and underwater. The center features more than 6,000 square feet (540 sq m) of interactive and dynamic exhibits including a mockup of the Aquarius Habitat, the world’s only underwater ocean laboratory, which is operated by Florida International University.

Once inside, you can explore exhibits interpreting the ecology of Keys habitats, from the upland pinelands through the hardwood hammock and beach dune. From there, you’ll travel down to the mangrove shoreline, where you can enter the sea (without getting your feet wet) to learn about the seagrass flats, hardbottom, coral reef, and deep-shelf communities. Stop by the center’s theater to catch “Reflections of the Florida Keys,” a short film on the diverse ecosystem of the Florida Keys by renowned ocean filmmaker Bob Talbot. Be sure to check out the Mote Marine Laboratory Living Reef exhibit, which includes a 2,500-gallon (9,475 liters) reef tank with living corals and tropical fish, a live Reef Cam, and other displays that highlight the coral reef environment. A walk through the beautiful marine life at the reef and shows how scientists live beneath the sea during research expeditions.

Planning a Trip

The Overseas Highway (U.S. Highway 1) spans the central corridor of islands with more than a hundred miles of roads and 42 bridges, making local dive sites some of the most accessible in the world. Keys residents orient themselves along two axes. The first is by referring to U.S. 1 mile markers (abbreviated “MM”), starting around 106 for Key Largo and famously terminating at MM 0 in Key West. From there, locals differentiate between the Gulf or Bay side (west of U.S. 1) and the ocean side (east of U.S. 1).

A local adage states that there are only three seasons in the Florida Keys: tourist season, lobster season and hurricane season. This is an important consideration when planning a trip, as these seasons will affect the overall experience. Tourist season generally runs from December to March, and is the time of year when “snowbirds” (Floridians’ term for winter-only residents) and other tourists flock to the tropical warmth of the Keys. Hurricane season officially starts in June and runs through November. Lobster season is technically from August to March, but the main event, which most travelers either consciously aim for or avoid, is “mini-season.” This two-day window in July allows recreational divers to get a first chance at the lobsters before the official opening of the commercial lobster season. If you plan to dive for lobster while in the Keys, be sure to check the sanctuary’s website for current information on dates, size and catch limits, and licensing requirements.

Pack your certification card, but you can leave your passport at home. The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is among the United States’ most diver-friendly destinations.